For as long as there have been cruisers, there have been snowbirds — those who sail south toward the tropics for winter, and back north again for summer. Good common sense motivates the migration, but so too do the mandates of insurance companies. Yacht-insurance policies have traditionally set latitude limits connected to the calendar, particularly around hurricane season: the policyholder agrees to move the boat north of some agreed-upon boundary line by June 1 or July 1 each year.

On the U.S. East Coast, that line could be Jacksonville, Florida, or Beaufort, North Carolina, or even Norfolk, Virginia. Some policies propose a latitude “box” that allows cruisers to sail farther south in summer to avoid the greatest hurricane risk: to Grenada or Trinidad or the ABC islands (Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao). Only after November 1 do these traditional policies allow cruisers back into the box.

But what if you want to stay in the hurricane box for a season or more? What if you want to avoid the time, cost and wear of two annual long-distance deliveries? That’s what we’re here to talk about.

Mythical Hurricane Holes

Of course, there have always been cruisers who stay through the storm season in the focal point of the hurricane zone. Generations of our forebears have passed down to us the names of legendary Caribbean hurricane holes: Ensenada Honda (Culebra), Gorda Sound (Virgin Gorda), Simpson Bay (St. Martin), English Harbour (Antigua), the north-coast rivers on Terre Haute and Terre Basse (Guadeloupe) and Marigot Bay (St. Lucia). The premise is simple: Find an enclosed bay with an entrance narrow enough to keep out the ocean swell. Proceed to the head of a creek, put out two or more good anchors off the stern with a long rode, and nose the bow as far as possible into the mangroves. Create a spiderweb of lines into the branches, then ride it out. Alternatively, find a hurricane hole so well-protected that you can hold out on your anchors alone.

Ensenada Honda in Culebra, midway between St. Thomas and Puerto Rico, was just such a mythical hurricane hole. For decades, its reputation was unmatched. Then came Hurricane Hugo in 1989. Some 200 boats had hustled themselves to Culebra before the first big winds blew. By the time the storm had passed — with sustained winds of 98 mph and gusts over 120 mph measured by the U.S. Navy at nearby Roosevelt Roads — more than 130 boats in Ensenada Honda were destroyed.Likewise, St. Martin’s Simpson Bay: When Hurricane Luis came through in 1995, it destroyed some 900 boats. The mere numbers were staggering, the human details gruesome.

Don Street’s Cruising Guide to the Lesser Antilles, published in 1966, was one of several iconic voices that initially pointed the way into some of these hidy-holes. But the 1989 destruction in Culebra profoundly changed Street’s mind. In an essay called “Reflections on Hugo,” he wrote: “There is no such thing as a hurricane hole in the Eastern Caribbean. They are all too crowded.” It took Street still another decade and a half to gently modify that statement with a strong caveat: “There are some hurricane holes in the Eastern Caribbean that are good holes if they do not get too crowded.”

All of which brings us to the present season. Will the hurricane hole you choose be too crowded when the eye of the storm comes bearing down on you? Will you be among the first boats to commandeer one of the few viable spots in the mangrove creeks? Will some boat come in behind you with high windage and short scope that puts your boat or your life at risk?

The problem with planning to ride out a storm anchored in a hurricane hole is that it leaves too many crucial factors out of your hands. Because that plan relies on an unstable context over which you have zero control, it means putting a little too much faith in hocus-pocus.

Straight Talk on Risk

Shawn Kucharski is the president of Falvey Yacht Insurance, a Rhode Island-based carrier that specializes in insuring recreational boats, luxury yachts and charter fleets in 40 countries.

“There’s realism,” Kucharski says. “We have seen cases where boat owners have taken the time, have tied down, have made sure their pumps are working, whose boats can be in a place where other boats are gone. Realistic insurers know that just because you have a great storm plan, it doesn’t mean you aren’t going to get hit or that you aren’t going to have damage. But if you have done the kind of risk management that’s going to lower that kind of exposure, you’re the type of boat owner we want to insure.”

What’s the difference between the hocus-pocus of blind faith and a realistic approach to risk management?

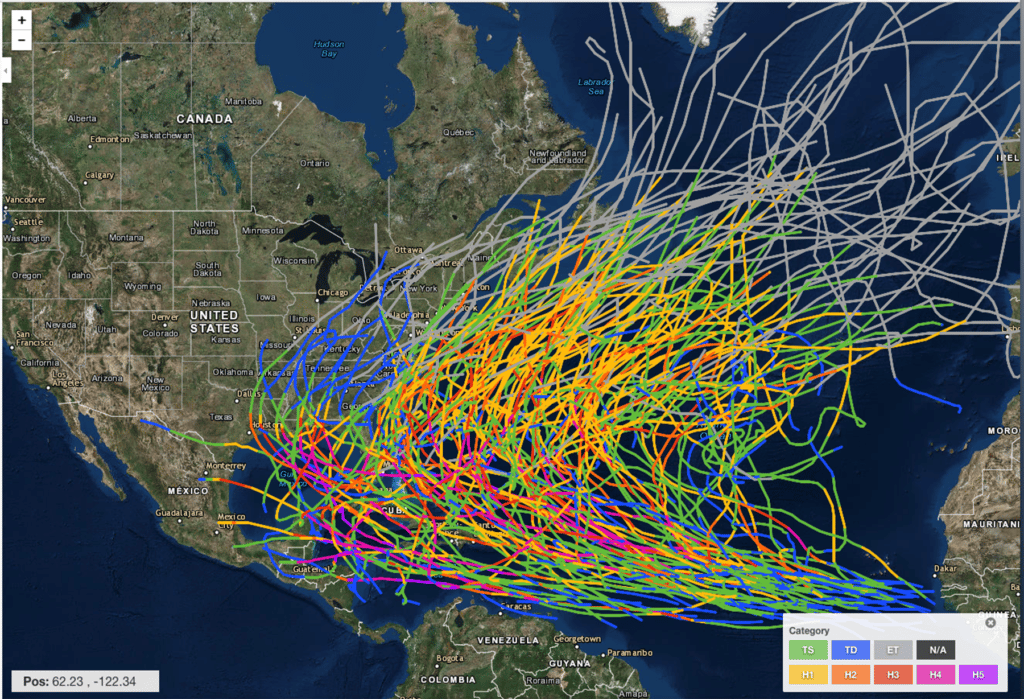

For starters, to understand past hurricane seasons, the U.S. National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration maintains a terrific website that shows the historical tracks of tropical cyclones. The screen shot on page 72 shows the tracks of all tropical storms or hurricanes in the North Atlantic basin from 1990 through 2016. It’s worth spending some time with this site and setting the filters to understand how tropical cyclones have traveled and behaved in the past.

Note that the colors indicate each storm’s strength on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale (Categories 1 through 5, with 1 starting at 74 mph and 5 going up from 157 mph).

Even though some yacht policies do exclude the hurricane box through summer and early fall altogether, it is possible to keep your boat fully insured and remain in the box. But it does mean working with insurers who specialize in cruising boats, and it also means preparing well in advance for any big storm.

Most insurers agree that remaining insured in the hurricane box starts with a detailed storm plan from the boat owner. Next comes the quality, technology, and track record of the marinas or boatyards on which that storm plan relies.

Mike Pellerin is the vice president of underwriting for BoatUS insurance, which is owned by Geico. BoatUS is so committed to acting on an approved storm plan in partnership with a proven marina, Pellerin says, that it will reimburse boat owners half the cost of their storm haul-out, up to $1,000, in the event of a named storm.

Other insurers have incentives too. Gowrie Group offers specialized insurance packages targeted toward cruising sailors. The Jackline Insurance Program is designed to protect boats and crew traveling throughout the world, including special coverage for Cuba. Gowrie’s Safe Harbor Marinas Insurance Program covers the full cost of hauling your boat “if it’s located in a Watch, Warning, or the 3-Day Track Forecast Cone for a Hurricane or Tropical Storm, as issued by NOAA.”

Your storm plan is the first key to qualifying for most policies. BoatUS offers a good set of generic guidelines on a Web page called Hurricane Preparation for Boaters, Marinas and Yacht Clubs. What insurers want to see from you is a comprehensive description of the steps you intend to take in the event of a storm — and the more detail, the better. The BoatUS Hurricane Preparation Worksheet provides a good start, but your particular circumstances will always merit their own details.

“If you’re an absentee owner,” says Pellerin, “we’ll want to see a contract from a marina or a contractor who will look after the boat in your absence.”

Kucharski agrees. “For us it always comes down to the -old-school, conservative aspect. The safest route if you’re not with the boat is if you have a contractor or crew, even if they’re part-time, someone who can check on the vessel. They don’t necessarily have to move it, just someone to tie it down if a storm is coming, check on pumps, that sort of thing.”

Engineered for Storms

The next most important thing, after your personal storm plan, is the place where you plan to ride out the storm. As risk managers, yacht insurers have access to and experience in interpreting lots of data: decades worth of records that show where past storm damage was concentrated, and where it was mitigated. At the same time, more and more boatyards and marinas in the hurricane zone are developing technology in their physical layout that lessens or eliminates damage in a storm.“The vast majority of the damage that’s done in storms,” says Kucharski, “is from the storm surge — not the wind. We can look back at Sandy in 2012, and we found boats miles inland. The wind’s not taking off even a 30-foot powerboat and moving it inland. It’s the storm surge that’s picking it up.”

For that reason, marinas have been investing heavily in dry racks. “With a strong dry rack that can bring a boat up 8 or 10 feet off the ground, you’re going to be able to weather most storms,” Kucharski says. “Next, if you can take that dry rack and put it inside a warehouse that’s designed to take wind exposure, the insurer will look very favorably on you.” Buildings deemed “cat-capable” are designed to withstand winds consistent with the Saffir-Simpson categories of hurricane-force winds.Of course, dry racks accommodate powerboats far better than sailboats, with their complicated rigs and underbodies. State-of-the-art marinas in storm territory have responded to this challenge with storm cradles and keel pits, as well as eyes embedded in concrete that allow the boatyard to strap the boat down against high winds and surge. Look for these marinas as you plan your trip.

For example, Nanny Cay Marina in Tortola offers seasonal tie-down for a $3,000 fee above the usual haul-out rate. Compare that to the cost of delivery and any reduction in your insurance premium that such a haul-out brings. Puerto del Rey on Puerto Rico’s east coast offers tie-down space for 350 to 450 boats. But be sure to check early and reserve space, if necessary. “This year we’re sold out,” said Jorge Gonzales, sales manager for Puerto del Rey, in early June. “We’re hoping to have an additional 100 to 150 spaces for next year.”

Mike Pellerin commends Jolly Harbour in Antigua for its investment in storm-prep haul-out. “We have boats in cradles on stands that are welded together, and boats in concrete keel pits,” says Jolly Harbour general manager Jo Lucas. “All boats on cradles have extra stands. Our tie-down anchors are set in concrete or have helix anchors set into the ground a minimum of 5 feet. Seventy-five percent of our yard is concrete storage.” Both Kucharski and Pellerin extol Loggerhead marinas in Florida for their storm-prep infrastructure. In addition to those, Kucharski also highlights River Forest Marina and American Custom Yachts, both in Stuart, Florida; Bluepoints Marina in Port Canaveral, Florida; and Marina One in Deerfield, Florida. For in-the-water storage, Kucharski points to City Marina in Charleston, South Carolina, as an example of a company that’s invested in high, surge-proof pilings and robust concrete docks.

As you look to your own cruising plans, have a chat with your insurer; he or she might be able to recommend marinas that have good track records with past storms. In fact, that conversation might help you not only with the places you cruise, but also the timing.

“Talk to your insurer,” says Kucharski. “November 1 is the official end of the hurricane season, and many insurers use that as the date for transit south. So that means marinas in the mid-Atlantic are chockablock with boats waiting.” Kucharski, ever the risk manager, says, “What’s the worst exposure? Late-season storms are more mid-Atlantic or farther north.” So, he says, tell your insurer: “I don’t want to be sitting with a hundred other boats in this marina just because November 1 is the date.”

Because, says Kucharski, your insurer doesn’t want that either.

– – –

CW editor-at-large Tim Murphy is an independent writer and editor based in Rhode Island.