Laka in Madagascar

As any new destination should be, Madagascar, still beyond the curve of the horizon, was a bit of a mystery to my wife, Nancy, and me. Lemurs, chameleons, jagged rock plateaus, rivers red with soil — we’d heard about that. But what about the coastal people? Or the waters surrounding the fourth largest island on Earth?

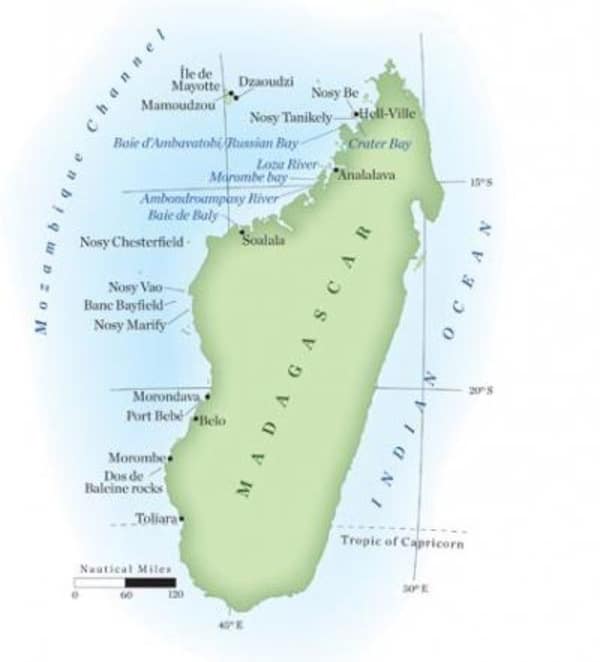

A thousand nautical miles of its east coast look over the Indian Ocean. And another thousand miles of its west shores are awash in the currents of the Mozambique Channel. We read that the tides of the east are a fraction of the range of those on the west side, where they routinely reach 12 feet. But there wasn’t much available information about the people, besides the CIA’s World Factbook statistics indicating the dire poverty.

Aboard the 94-foot expedition yacht Whale Song, we’d just left Île de Mayotte, which is officially an overseas territory of France and is, in truth, a colonial dump, if you pardon the straight talk. It did have marine services: a boatyard in the town of Dzaoudzi, on the nearby islet of Petite Terre; welders, painters, mechanics and some marine hardware are available on Grand Terre, in the city of Mamoudzou. Despite these exotic names right out of Sinbad the Sailor-type tales, the place offered only basic support in a dusty, rusty, crowded sort of way.

On the other hand, Nosy Be, the island off the northwest coast of Madagascar that was our landfall, surfaced ahead afloat on lazy swells swirling purple under a pink-streaked dawn sky. A crop of crescent sails from local boats loomed white against distant bluish hills. Coming close to its main town, Hell-Ville, we crossed tracks with dozens of local boutres, lateen-rigged dhow-like cargo carriers whose design unmistakably originated in the Arab world. Hell-Ville, named for a long-dead French admiral, is the administrative center of northwestern Madagascar. We dealt with the officials and made some produce purchases, then backtracked a mile or so to Crater Bay, where most charter and cruising yachts hang out. Outrigger canoes loaded with hay, low in the water to the gunwales, wove through mostly French yachts of all designs and sizes. Charter boats skippered by French expats — clones of the late Bernard Moitessier, the bronzed super solo sailor — occupied most of the bay.

The boats from Dream Yacht Charter favored the playgrounds of the bays and islands near Nosy Be. After a short snorkel by the popular Nosy Tanikely, we soon headed south along the west coast. Fifteen miles later we swung to our anchor, the only other vessel an outrigger pirogue that entered behind us and also sought solitude under a rocky point.

This spot, the practically landlocked Baie Ambavatobi, stretches into several long finger bays filled with exploring challenges. Russian Bay, its other charted name, harks back to 1905, when some deserting Russian sailors fleeing from the Japanese found refuge here and went troppo under the Madagascar palms.

There are ways to navigate pretty far into the interior of Madagascar. We charged into the Loza River, just a bit farther down the west coast. After the wide entrance, the deep river flowed reddish between gentle rounded hills. Small patches of greenery bordered a few small clusters of huts scattered close to its banks and ravines, which had retained moisture after rains. Large outrigger pirogues loaded with waving passengers crossed the river under great spreads of lateen sails. A zebu, a type of cattle, lumbered down to one of the ferry landings. Was it waiting for a boat?

After about 10 miles, the obvious deep channel ended, and the river spread into a broad lagoon that we guessed was too shallow to tackle without a chart. We headed back against a strengthening onshore breeze. Low tide exposed mud flats at Analalava, the village at the Loza River’s mouth where local boats lay on their sides on the mud. At the edge of the channel, the crew of a large dhow hauled the anchor and struggled to get the immense canvas of the lateen mainsail under control.

Given a chance, nature turns lush in the coastal belt. Far up in Morombe Bay, the hilly sand dunes of the outer coast disappeared, and we anchored among islets carrying stands of fat baobabs. Here in the higher trees with thorny trunks, grand vasa parrots cruised overhead, unafraid of the even larger raptors wheeling above.

Farther south along the coast, the small Ambondroampasy River wouldn’t admit our draft of 8½ feet, so we anchored off in a smooth sea and explored with the dinghy. The posh Anjajavy Lodge on the south bank protects a chunk of Madagascar’s natural world. Sifaka lemurs, diurnal creatures unlike other lemurs, watched our progress through the trails with round, innocent eyes. On a sandy hook of the north riverbank lived a boatbuilder, his house awash in naturally curved crooks of timber and boats of different sizes and shapes awaiting repairs.

Most of the Vezo people along the west shores of Madagascar live in small villages, typically in little huts of reeds and bamboo. The majority of them relaxed around their homes, quietly excited at having visitors. The most energy radiated from a cluster of women who, under a mango tree, swung long pestles made of shiny hardwood to pound rice in wooden mortars. They shrieked with laughter at their images in a digital camera and posed again with improved postures. In the doorway of a hut, a man strummed a stringed instrument, homemade and square-cornered. A muscular fellow, his ax razor sharp, put the finishing and precise touches on small pirogues that he and his wife had under construction.

The populous town of Soalala, on the other side of Baie de Baly, looked prosperous. Two schooners leaned over, grounded by the low tide; a crewman worked at painting. An outrigger unloaded baskets of fish to waiting women. Across, in a little cove, a generator throbbed in a small French-owned shrimp-processing plant.

Port Bebé, off Morondava, presents a typical picture of coastal life. Only the local outrigger boats can enter through the shoals. The schooners wait for high tide and the onshore breeze, then rush in through the narrow creek to town. They carry sugar, rice, flour and some passengers. Strangely enough, a shed on the wharf was turning out fiberglass copies of the outriggers, rigged with steel masts, perhaps the result of a grant from the European Union.

Restricted by our draft, we stayed anchored outside, in the path of the daily migration of the fishing fleet; they went out with the offshore breeze and came back with the onshore wind. In town, several vendors traded in suspension springs and rods; Madagascar roads are terrible. Others sold homemade wick lamps soldered from tins that once held beans. A seamstress worked her Chinese sewing machine on the sidewalk. Several general stores sold dusty rolls of colorful cloth, and plates, cups, tools and trinkets made in China.

Offshore islands, islets and sandbars were busy with humans. The sandy islands of Nosy Chesterfield, Nosy Vao, Nosy Marify and Banc Bayfield bristled with camps, boats hauled out and sails serving as tents; it was turtle-egging time. So it was a pleasant surprise to see green turtles when we dove through clouds of moorish idols at Dos de Baleine rocks, underwater outcrops that we located at 22 degrees 14.83 minutes south latitude and 43 degrees 11.00 minutes west longitude. Charting for Madagascar waters is particularly bad in this area, where we found GPS fixes differed by as much as 1½ nautical miles and a half from the paper and digital charts.

Belo-Sur-Mer has always been the local center of schooner boatbuilding. More than 20 hulls under construction rested beneath the palms on the waterfront beach. But obtaining timber costs money, and many projects slumbered, waiting for funds. One gleaming hull already rigged was an exception. The owner of a budding resort needed the vessel for her customers. Two other established resorts overlooked a blue lagoon just outside the village. High tide is of an essence to get over the 6-foot bar, but inside, the protection was perfect. And the views: shimmering sand dunes, the dark silhouettes of children foraging at low tide for seafood tidbits, a green margin of low forest to the east, rows of coconut palms to the north, and to seaward, the glistening expanse of Mozambique Channel.

Toliara was our last stop on the southwest end of the island. Extensive flats front the town landing, and as our dinghy grounded before getting close enough, two buffalo-driven carts approached. It took a few minutes to understand that they were the taxis to the dry land. Everyone uses them, including tourists who join local boats for snorkeling outings. On land, the taxis gave way to rickshaws pulled by marathon-legged men.

For the local ships working under sail, Toliara is their southern terminus on the west coast. We passed these ancient-looking craft every day. As a rule, when our boat began overtaking a gaff-rigged schooner, two crewmen would race up the masts, past the gaffs, and unfurl the topsails so the boat would speed up. Almost every ship carried a guy strumming his square-cornered homemade Malagasy guitar and singing. Friendly hands would wave. With the prevailing offshore wind that month, the sailing life seemed free and easy.

Toliara has a wharf where the waves get very rough in the afternoon breeze despite an offshore reef that acts as a natural breakwater. Customs wants your boat tied up for clearing in and out, so after dropping an anchor to pull ourselves off later, we docked right as the sun rose. Even before the wind piped up, our ship was off and heading out, and we were full of regret for not staying longer among these happy people.

Madagascar Snapshot

Wind and weather: From April to June, the light northeast winds of the morning change to fresh southwest winds in the afternoon. East winds, up to 25 knots, prevail from July until October. We were there for part of October and all of November and experienced variable winds and often land breezes, which were light and offshore at night and stronger onshore in the afternoon. Most cyclone activity happens between December and March.

Navigation: Use French charts from the Service Hydrographique de la Marine, but treat them with caution. Digital charting is also unreliable, so keep a very good lookout for breakers on shoals. On the west coast, tidal ranges often reach 12 feet.

Communications: Mobile-phone coverage is available only near Nosy Be. Satellite phones can be rented from Dream Yacht Charter.

Charters: Companies offering crewed and bareboat charters include Dream Yacht Charter, located in Crater Bay, near Hell-Ville on Nosy Be island.

Safety: At night at Nosy Be anchorages, lock the boat, hoist dinghies and secure outboards.

After running yachts professionally, Tom Zydler and his wife, Nancy, now cruise cold northern waters on Frances B, their 1990 Mason 44, an upgrade from their 1961 engineless 38-foot yawl, Mollymawk. This article first appeared in the October 2013 issue of Cruising World.