As a frugal sea gypsy, I delight in telling people about all the expensive stuff they don’t need to go cruising. But you do need a boat, and now is an ideal time to buy one. Why? Because good cruising vessels have never been so available, so reliable and so affordable.

If you are young, it’s the perfect time to start sailing. Sailboats are ideal machines for transitioning from youth to adulthood. I purchased my first one at 15, and the responsibility of it caused me to morph from boy to man overnight. Once I’d spent a summer sailing the Great Lakes with my own tiller in my hand, I knew that freedom was my life goal, not corporate chains.

I have, in essence, never looked back.

It’s even better if you’re raising a young family. The kids will love being on the boat. I’m not sure which I enjoyed more: steering my own vessel at 15 years of age, or watching our daughter, Roma Orion, steer our Hughes 38 Wild Card when she was that age. And I’ll never forget the day, a few years later, when she rowed up excitedly in her own dinghy, boated her oars perfectly and announced she’d just won a presidential merit scholarship to Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts.

“That’s wonderful, Roma!” I said, feeling the burden of paying for higher education unexpectedly lifted from my shoulders. “Absolutely wonderful! And while you’re away to university, your mother and I are going to sail around the world.”

She knew this was our lifelong dream. So she was hugging us as we were hugging her.

But perhaps the best time to go to sea is when you’re an empty nester. You and your spouse will finally have a little well-deserved “me” time. Your focus will be changing, your horizons of interest expanding with your maturity. What better way to explore the world (and rediscover the contours of your romance) than on a small sailboat on a big ocean.

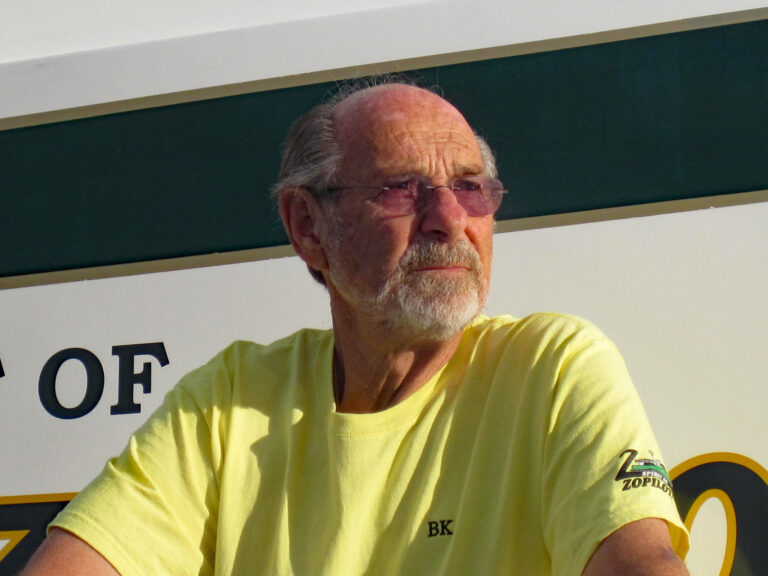

This is where my wife, Carolyn, and I are right now, on the eve of our departure on our fourth circumnavigation. As we cruise, I tell everyone we’re on our honeymoon, because we are. The boat has allowed us to be closer, more intimate and far less abashed than most couples. I can honestly say my wife and our wrinkles grow more beautiful with each mile sailed, each continent reached. Since we first set sail, Carolyn has given me her youth, and I am honored and ever grateful.

Not too long ago, Tahiti loomed over the horizon after 48 days at sea. I said, “Let’s keep going to the Torres Strait.”

“But, Fatty,” said Carolyn, “that would be another month at sea. And besides, what’s in the Torres Strait?”

“Nothing,” I confessed. “But I want to spend another month offshore in your arms, without the vexation of shore.”

And it was true. You go ashore, you answer your email. Suddenly, reality intrudes. You’re reminded in a million ways why you should worry about a billion things, when, in reality, you should worry about none.

These irritations aren’t inconsequential. Taken all together, they’re a big distraction. Social media isn’t the same as being social. One million Facebook friends don’t equal one smiling Polynesian in your cockpit.

Our postal drop is at a place called Connections on St. John. We pick up our mail, on average, every five to eight years. We feel this is about right, as many of our most pressing problems tend to resolve themselves over time.

Just because landlubbers get excited by certain nonsensical events that take place ashore, there’s no reason for seasoned sea gypsies to get all riled up. What angers you, conquers you. So why not simply avoid the vexation of modern society? Happiness has no price tag, so why pay and pay and pay? Why ask what the rules are when they’re stacked against you?

Our Wauquiez ketch Ganesh is our own small country. I am king; Carolyn is queen. Occasionally, our subjects (our daughter and two grandkids) visit. At any moment, we can vote with our keel. The entire world is on our menu of delectable choices. We can cherry-pick our laws. Our world is rainbow-hued, and the concepts of brotherhood, equality, respect and justice are used daily. Happiness is a choice. Freedom exists. All you have to do is rip the societal blinders off and toss them in your gurgling wake.

As we grow older, we realize that change is the only constant in life, so ultimately, as Darwin pointed out, adaptation is more important than intelligence. And what better platform is there to evolve globally than from the deck of a modest vessel with all the exotic ports on the planet to choose from?

Perhaps, for instance, you’ll find yourself in your sunset years making landfall in Southeast Asia. Don’t be surprised if unexpectedly confronted by a group of Asian teenagers on a dark night on a deserted beach, they will stop and ask solicitously, “Are you all right, Uncle?” It’s the sort of place where no one has a lock on their boat — or knows why one would.

Our world is rainbow-hued, and the concepts of brotherhood, equality, respect and justice are used daily. Happiness is a choice. Freedom exists.

Long-term anchoring is free, sailors are welcome, marinas are cheap and the nutritious food is tasty and affordable. Better yet, did I mention that you can live like a king (or rajah) on Social Security?

But you don’t have to retire to strike out anew for distant shores. When we completed our last circumnavigation and found ourselves back in the U.S. Virgin Islands, we observed that the fastest- growing segment of the cruising community on St. John seemed to be single young ladies. It was before last fall, when hurricanes took their toll and set the islands back a bit. These women often arrived on vacation, fell in love with Love City (what the locals call Cruz Bay), got a job waitressing or bartending in order to stay in paradise, and moved aboard a derelict vessel to save money. Eventually, they would meet some real liveaboards and ultimately buy a well-found boat and cruise the Caribbean as skippers of their own destiny.

Carolyn and I know three other women captains who may have arrived in the Caribbean as the “reluctant wife,” but along the way fell in love with the cruising lifestyle, and ultimately said to their husbands who wanted to move back ashore, “You keep the house, honey. I’ll keep the boat!”

These newfound captains have been cutting a wide, lively swath through the cruising community, and loving it.

“All my life I’ve been taking care of someone: my husband, my children, my parents. Now, finally, I’m taking care of myself, looking after my needs,” one female singlehander told me in Tonga. “I’ve always wanted to see the world and to call my own shots. Why wait when you’re only getting older? What better time than now, and what better way to live my final dream than from the deck of my own movable seashell?”

When I first saw the cruising sailboat Sea Legs anchored in Coral Bay, I thought it had the stupidest deck layout ever. I mean, who runs their anchor chain through a PVC trough all the way back to a windlass in the cockpit?

Then I noticed the wheelchair lashed on deck.

Tommy Sea Legs, as he was called throughout the Caribbean, and I often used to drink together back in the day. He’d claim he had the advantage at sea with “less distance to fall.”

The skipper of Hero had stepped on a Claymore mine in Vietnam and had lost one hand as well as both legs. He sculled his dinghy with a single oar and did an amazingly graceful one-armed chin-up to gain the deck of his Hans Christian 40.

The skipper of Gulliver also lacked one leg. Once, in an emergency, he cast it off to hop forward during a St. Augustine squall, much to the amazement of our 3-year-old daughter, Roma.

Perhaps the most amazing of all the bluewater sailors we’ve met were a young couple in a dinghy searching for a mooring ball in New Zealand’s Bay of Islands — by feel — or that’s what it looked like anyway. At first I thought they were blind drunk, so I went to assist. It turns out they weren’t drunk, just blind.

We soon learned the pair, Scott Duncan and Pamela Habek, had set off from San Francisco in 2004, attempting to become the first legally blind couple to sail around the world.

“Isn’t it scary,” I asked, slack-jawed, “being at sea and blind?”

“At first,” the skipper said. “But not being able to see in a place there’s probably nothing to see isn’t so bad.”

Yes, it takes all kinds, and each of these kinds has a boat. It’s their global ticket to inexpensive international adventure. I’m not amazed how many people now live aboard or how fast the cruising community is growing worldwide, I’m amazed by how many dirt-dwellers don’t sail the seas.

They literally don’t know what they’re missing.