Picture this: Youre at the helm of a big ketch, loping gently through the blue waters of the West Indies. Your wife, sunbathing on the large foredeck cushion, looks great in her new yellow-and-black swimsuit. Shes happy, and that makes you happy. And your young son, well, hes just seen his first sea turtle underwater and is trying to identify its species in a field guide. He sits in the cockpit beside you, wrapped in a towel, shaded by the wide bimini. Youre feeling sort of lustful and fatherly at the same time. Magnanimous for sure. You have one hand on the steering wheel, and youre aiming for a white ribbon of beach about three miles away, the evenings anchorage.

The only thing that could improve this scene is a beverage, and damn! Next thing you know, the captain puts a cold one right between the four fingers and opposing thumb of your free hand. All you have to do is squeeze.

Make a wish, dude, youre on a streak!

Far from the Big Dig

Our week of living hedonistically was a study in contrasts, beginning in black and white with the airport shuttle speeding toward Boston’s Logan International Airport along the Southeast Expressway, then through several miles of Big Dig construction (the world’s largest public-works project) where entire streets disappear and reappear overnight, miles of hastily erected chain-link fences protect against cavernous holes dug under the city, monoliths of concrete and rebar are frozen against the gray sky, and everywhere there’s pavement diving underground and ramping into the sky. The chaos all around was like a topo map of my brain–dust and rubble, short circuits and fried wiring. My wife, Andra, and I had been working too hard at too many jobs. We’d become frenzied, hollow-cheeked insomniacs, overstimulated by the synthetic sounds of the e-world; we’d grown surly, nipping at one another.

Time for a time-out, or how about a weeklong movie about a family having fun, starring us?

The Logan Express bus driver tossed our seven bags onto the curb and left us inhaling his fumes. Our 12-year-old son, Stephen, suggested we rent a “Smarte Carte,” but being one of those stubborn, self-sufficient types whod rather load himself like a packhorse than cave in to a porter or pay a buck fifty for a sissy cart, I shouldered two bags to a side, steadied myself, and shuddered forward. Like Dorothy spiraling toward Oz, I was ready for color and a happy landing.

Working the Numbers

A year had passed since we sold Viva, the Tartan 44 in which we cruised New England for six years. Daysailing the same course for the hundred and first time was losing its appeal; we wanted to relive the excitement of making new ports. We also sought a complete (if temporary) respite from responsibility, which is what ultimately led us to forgo a bareboat charter in favor of a crewed one. Andra was rather insistent, reminding me that we’ve never gone anywhere when I haven’t had to work on the boat. And if, on top of watching me draped over the engine with wrenches in hand, she had to cook or do dishes, it would be no vacation at all.

Setting aside my first notion that a crewed charter was much more expensive than a bareboat, I made some calls and started putting together the numbers. Surprisingly, it was close. The key is a realistic assessment of what you end up spending for food, liquor, dinghy, fuel, water, and the like. Its always more than you expect. The crewed-charter rates are all-inclusive, so you know what youre in for from the get-go. We like that. Not to mention skipping the obligatory bareboat checkout and grocery shopping that, combined, can knock a day off your vacation.

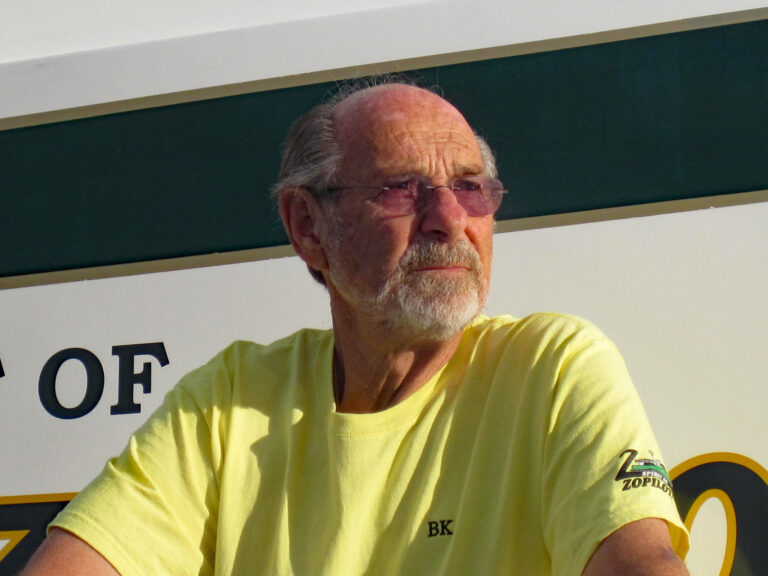

On veteran charter broker Lynn Jachneys recommendation, we signed on with Oliver Deligny, a St. Lucian (French father, St. Lucian mother) with 14 years experience chartering the Gulfstar 50 La Creole; for many years, he ran a corporate yacht for the industrial equipment manufacturer Caterpillar and, before that, a 91-foot French-Canadian yacht. With 16 transatlantics under his keel, Oliver now works out of the comparatively placid waters of Charlotte Amalie, St. Thomas, U.S. Virgin Islands. Take him for a few days, or take him for a month. One client had Oliver sail him all the way to Venezuela. Another had him park La Creole at a hotel dock just so he could entertain customers in the cockpit.

Whatever.

We met Oliver and his Argentine cook, Candela, at the Crown Bay Marina, where La Creole had been entered in the annual charter-boat show, again winning an award for best varnish job. Steves bags were taken to the forward cabin, ours to the aft cabin, and by the time we changed into T-shirts and shorts, we were under way, first stop Christmas Cove at Great St. James Island, between St. Thomas and St. John. Id resisted the compulsion to plan our itinerary, postponing such decisions until I had a chance to consult with Oliver. Our conversation went like this, initiated by Oliver:

“What would you like to do this week?”

“Not much.”

“Fine by me.”

Oliver and I saw eye to eye. Or so he made me feel, and thats all that matters. (In the hospitality business, sincerity is necessarily ambiguous.)

Despite this mandate, in the ensuing week we visited all of the major islands in the U.S. and British Virgin Islands, many of the smaller ones, and did so at a leisurely pace. Such is their proximity to one another.

It’s a Cataleptic Life

The cruise was Steve’s introduction to the West Indies. His passions are fish and fishing. At home he cares for several aquariums, subscribes to a number of fishing magazines, and owns rods and reels for every variation of the sport from deep-sea trolling to spin casting to fly fishing. He’d brought his complete, weighty tackle box plus two carefully selected rods.

In the evening, Oliver collected table scraps to chum the waters. Grunts, snappers, and remora seemed to hit any type of bait–bacon to bread. The water is so clear, of course, that aiming the beam of a small flashlight at the bait suspended six feet down catches the iridescent and darting shapes of fish making passes. All hooked fish were admired, photographed, recorded in our unofficial log, and released.

Slowly, the three of us were sinking into tropical indolence. We had no computers to wake and rise to, no email, no telephone ringing. Anxiety over unfinished and awaiting tasks began to fade. Each day we sailed, ate, and snorkeled, sailed, ate, and snorkeled. . . .

Candelas culinary cleverness was a highlight of each day–perhaps grilled sea bass or shrimp pasta, asparagus, pumpkin and coconut soup, Mediterranean salad, fruit, fresh baked brownies, bananas flambé. Most evenings we dined in the cockpit, illuminated first by an inverted basket lamp hung from the bimini frames, later by the swelling moon. As the days passed, the profile of my stomach was waxing at the same rate as the moon, and by the end of the week, both were in the same state of fullness.

Oliver said, “There are three tings that happen on de boat: You will be hungry all de time. You will be tired all de time. And you will be sleepy all de time. Thats what de salt air do.”

It was true. At home, Andra and I normally sleep six to seven hours. Our first night on La Creole, we logged nine, which we attributed to the stress of the trip. But each succeeding night we fell asleep earlier and arose later, until it seemed we snoozed half of each day. The less we did, the less we did. Spoiled, somnolent, satiated, we were the childlike Eloi of H.G. Wells The Time Machine (starring Rod Taylor as the Time Traveler in the movie version), clothed and fed for consumption by the underground Morlocks. Perhaps my perspective was a little skewed, but as Morlocks was the way I now viewed practically everyone back home in the, you know, rat race.

Oliver proved to be a most amiable captain and companion, especially to Steve, who regarded his elder as if he were an oracle of the deep, the very voice of Poseidon. If Oliver said there were no manta rays in such and such a bay, then there were none. If he said the fish wouldnt bite before dark, they wouldnt.

Oliver was happy to make conversation whenever we desired or, when we fell silent, simply to drift off to some other part of the boat. Candela, bronze and buxom, said she was the daughter of a famous Argentine model whod bought several properties in the Virgin Islands back in the 1970s. When Candela wasnt working in the galley (which was rare), she could be found lounging languorously, straw hat shading her face, a brightly colored something or other falling off her hips, a leg hanging over the coaming catlike.

Into the Wet

Each day passed in this manner:

Wake at 6 a.m.; lounge until the sun comes up an hour later.

Breakfast topsides. (The place mats and napkins are never repeated.)

Swim and snorkel. (Coral reefs are found in nearly every anchorage.)

Sail for a few hours to another island, where we stop for lunch.

Swim and snorkel.

Lunch. (Perhaps a pasta salad in a hollowed avocado, a roll, fresh butter, and caramel flan for dessert.) Relax.

Swim and snorkel.

Sail to our evening’s anchorage.

Swim and snorkel.

Cocktails and hors d’oeuvres at 5 p.m.

Dinner at 7 p.m.

Steve and Oliver fish.

Cards, video, or conversation.

Asleep by 9 p.m.

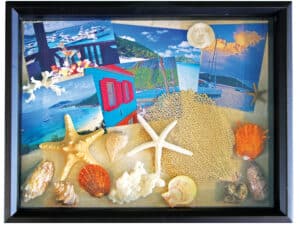

As the anchorages, beaches, and reefs compiled, we lost track of where wed been, or at least their sequence.

“Where were we yesterday?” one of us would ask. “Norman? Or was that St. John?”

“Dunno.”

Now, with benefit of my notes, photographs, and a clear head (thanks to a drafty office window), I can give an accurate itinerary. From Christmas Cove we rounded the northern side of St. John, stopping at several gorgeous beaches inside the vast Virgin Islands National Park that occupies two-thirds of the island: Cinnamon Bay, Trunk Bay, Hawksnest Bay. Apparently unable to fake them in L.A., Hollywood makes movies–The Four Seasons, starring Alan Alda, for instance–at these sites, and that gives me hope that this trip is–pinch myself–real, not just a 50-foot prop and a good acting job.

Sopers Hole, at the western end of Tortola, has a customs office at which people off boats and ferries

are expected to clear into the British Virgin Islands. There’s not much to the town other than some

waterfront shops and the Pusser’s Landing pub and store complex, one of five throughout the islands.

Heading east, there are good anchorages at Norman, Peter, and Salt islands. Coming and going, we stopped at all three. Norman, supposedly the inspiration for Robert Louis Stevensons Treasure Island, offers good snorkeling off–you guessed it–Treasure Point. Moorings here, as elsewhere in the islands, are available for boats to 60 feet. At Norman, Steve saw his first barracuda hovering under La Creole.

Sputtering to the surface, he yelled, “Oliver! Check it out! Theres a barracuda under the boat!”

Oliver leaned over the side. “Thats Henry. Hes my friend. He always know my boat and come to visit.”

Steve immediately called for his disposable underwater camera and dove again.

“Most kids that age see a barracuda, they jump out of de water,” Oliver said admiringly. “Not Steve. Hes goin back for a closer look!”

Next up was Virgin Gorda and The Baths, large boulders strewn down the hillside and into the water as if flung by a giant hand. Because of a strong surf that made landing the dinghy dangerous, Oliver instead took us up the island a few miles to Spanish Town, where we took a taxi back to the hill overlooking the park, part of the B.V.I. National Parks Trust. Steve was glad we did, spotting along the trail down a number of iguanas and red-legged hermit crabs living inside hollow coconuts. The trail through The Baths, dappled with sunlight and wetted by thunderous surf hissing through tight passages, is humbling and unforgettable.

Bitter End Yacht Club lies at the northeasternmost end of Virgin Gorda, hence its name. Coming in, we saw Steve and Linda Dashews Beowulf, hailing them as we passed. Later they dinghied over for a visit; they said theyd been invited to participate in Steve Blacks Caribbean 1500 cruisers rally from Norfolk, Virginia. At 78 feet, Beowulf was the scratch boat; when we left the next day, no others were yet visible on the blue-over-blue horizon.

Heading back westward, we stopped for visits at those anchorages wed skipped coming east. At Cooper Island, we swam ashore and chatted up a couple from Oregon staying at the Cooper Island Beach Club. The man and woman sat in lawn chairs pulled into the intertidal zone. She was lounging with a book in her lap; he, flippers and face mask.

Given that theres neither town nor ferry service to the island, I asked, “What do you do all day?”

“Read,” she said. “He”–meaning her husband–“likes to dive, so some days he has one of the scuba boats pick him up on the way by. Other than that, we just sit here. It isn’t for everybody, but it suits us.” They were, she said, going to be tranquilized for another 12 days.

As we prepared to swim back to La Creole, the man offered to show us an octopus sucking the guts of a conch out of its shell. It was very difficult to actually see this, and as he pointed and I tried to discern the brown blob of the octopus’s head camouflaged in a crevice of coral, I realized the man must have spent a lot of time today staring down on this small reef. Then again, he had the time, mon, he had the time.

Sailing downwind, we rolled through Sir Francis Drake Channel with the verdant hills of the islands to either side. Rounding West End, Tortola, we coasted to a stop in a confused current and fickle winds. A charter catamaran coming out of Jost Van Dyke did a 360 trying to head up so the mainsail could be raised. Drifting between the rocky arm of West End to the east and Great Thatch Island to the west, we made, as if caught in a whirlpool, no discernible progress until suddenly, for no obvious reason, we were cast out.

Soon we anchored in White Bay, Jost Van Dyke, and there spent the afternoon snorkeling the reef and walking ashore. Before leaving, Oliver took us around the promontory to Great Harbour so that we might have a drink at Foxys, the famous beachside bar thats said to host the worlds second largest New Years Eve party (after Times Square in New York City). Today there were but three or four patrons, and thats as Id have it any day–still and desultory.

Back to the Grind

Alas, it ended, and we said our good-byes to Oliver and Candela. “For a week,” she’d warned me, “I’ll be your new best friend. Who else are you going to talk to?”

Andra and I werent cynical but must have known this, which made our parting pleasant and easier. More touching was Steves separation from Oliver, for the two had shared some happy and private moments fishing. (Steve had, Oliver whispered, even shared the name of his “girlfriend,” intelligence to which not even his parents were yet privy.)

We spent one pleasant night ashore in Charlotte Amalie, at a hotel in Frenchtown, if for no other reason than to begin recompressing. But the effects of cruising aboard La Creole lingered, and in some subtle ways, were changed.

Back at Logan airport, back in black and white, Steve collected our many bags off the conveyor belt, heavy with gear. Outside, among the turning wheels and grinding gears, I could see the Morlocks. They were waiting for us, the Eloi, and we had no choice but to go out and accept our fate.

Steve and I started to throw the bags up on our shoulders like the Sherpa Spurrs of old. Then I stopped, felt in my pocket, and produced six quarters.

“Steve,” I said. “Get us one of those Smarte Cartes, will ya?”

Dan Spurr, editor of Practical Sailor, is a former CW senior editor and the author, most recently, of Heart of Glass: Fiberglass Boats and the Men Who Made Them (International Marine/McGraw-Hill, $28).