The sailing writer from America was getting nowhere. Hed arrived in Auckland, New Zealand, to cover the 1990 Whitbread Round-the-World Race for Sailing World magazine and, with an imminent deadline, was having zero luck scoring an interview from the events biggest star, the local hero Peter Blake, who was winning handily. To the Kiwis PR flacks he pleaded, “No Blake, no story!” Didnt matter. Much too busy. No dice.

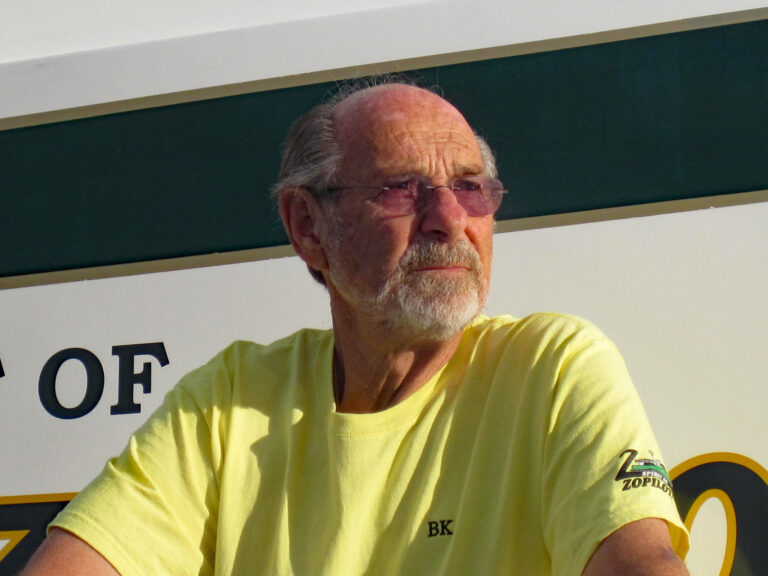

His options dwindling, the nervous scribe launched a dockside Blake vigil. Very early one morning, before the masses stirred, he cornered Blake as he was stepping aboard his boat, Steinlager II. At six feet four inches, with a distinctive mustache and a blond Prince Valiant mane, he hadnt exactly been incognito.

The reporter sheepishly made his request and prepared for the rebuke. But Blake said, “Cmon aboard, lets go below, quick before anyone spots us.” And for the next two full hours, Blake expounded on sailing, the race, the sea, his life, and anything else that was asked of him. He answered every question until there were no more. Only then did the grateful writer leave, transfixed by the mans generosity, insights, and intelligence.

Of course, the writer, who remembers it like it was yesterday, was me.

In early December, memories of Blake were invoked around the world after the 53-year-old sailor was shot and killed when his 119-foot research vessel, Seamaster, was boarded near the mouth of the Amazon River. In New Zealand, a grieving nation came to a standstill as people tried to make sense of the senseless incident.

Blakes sailing career was unparalleled. He won the closest thing sailing has to a Triple Crown: the Whitbread, the Americas Cup, and the Trophée Jules Verne, for the fastest nonstop circumnavigation. For his exploits, he was awarded a knighthood, and its no exaggeration to say that he was as big a hero in his homeland as Everest conqueror Sir Edmund Hillary. In my view, he was easily the greatest, most accomplished sailor of our time.

Yet Blakes finest deeds may have still been ahead of him. His racing days over, he first became the head of The Cousteau Society, then struck out on his own. Blake loved the sea, and his open-ended plan was to lead expeditions for oceanographic research and environmental awareness. It was at the conclusion of such a trip that his life came to an end.

Blakes passing will no doubt reopen the controversial dialogue about guns on boats. Though at this writing the full details of the incident remain sketchy, Blake was wielding a rifle when he was shot twice and mortally wounded. I cant help but think that he might be alive today if hed left his weapon below and let the thieves come aboard–they were reportedly after cameras, watches, and cash, not a mans life–and go unchallenged about their dirty, petty business.

Which, as so many of his friends said after he was gone, was the very last bloody thing Sir Peter was going to let anyone get away with.

So now, Blakes wife and two teenagers go forth husbandless and fatherless, Seamaster is short her skipper, the sailing arena has lost a legend, and the worlds oceans ebb and flow with one less impassioned advocate and adventurer setting his course upon them.

In the intervening years following our first meeting, I was honored with many more wonderful chats with Blake. Yet that first one still stands out. For that was the day Blake proved he was a whole lot more than a rock-star racer–he was, and will be remembered as, a helluva good guy.