PassageNotes0607

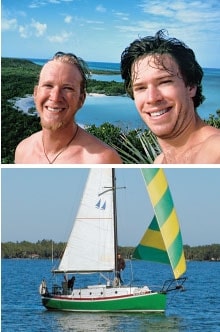

My brother, Richard, and I recently traveled from Gloucester Point, Virginia, to the Bahamas on Margarita, a 24-foot Bruce Roberts Tom Thumb that my uncle, John Larkum, built in his backyard. Because the trip was my first, I had to learn how to walk on a sailboat, raise a jib, and head into the wind, among about a million other things. However, the most surprising lesson I learned was that 99.9 percent of the cruising world is retired. This number isn’t scientifically proven, but I’m confident that it’s fairly accurate. My discovery was especially shocking because my brother has many friends younger than 30 who own boats and have extensive cruising experience. Although he and I have four young, boat-owning friends all hailing from Lancaster County, on the Northern Neck of Virginia, where we’re from, and whom we’ve known since childhood, we met not a single other young sailor during our three-month voyage.

I hadn’t really expected to meet many sailors my age, as most young adults are busy working their ways into comfortable careers, scrimping and saving so that they, too, may one day enjoy a carefree retirement. I did, however, expect to see the occasional salty puppy enjoying a year off while still willing and able to do so. After all, even I knew that once you’ve bought a boat, the sailing lifestyle can be fairly inexpensive and relatively easy, a seemingly perfect choice for a semi-responsible 20-something. Yet for some reason, my generation seems to be unaware of this. So in hopes of promoting the great lifestyle of sailing, especially to the young and the inexperienced, I’ll profile several young sailors who’ve decided to begin the cruising life earlier than most.

I’m 24 years old and a graduate of Virginia’s College of William and Mary. Because my brother already had a boat, my transition into the sailing world was pretty easy. I simply reserved a time on the boat, saved my summer earnings, and joined Richard on his annual winter trip to the Bahamas. Before we left Sarah’s Creek (which is in Gloucester Point) on December 27, 2005, I’d only spent a grand total of 20 hours on Margarita-or any other sailboat, for that matter. Over the next three months, I learned how to read the wind, interpret a chart, navigate at night, follow the waves, and cook eggs while barraged by high seas. We covered roughly 1,500 nautical miles from Sarah’s Creek to Little Farmer’s Cay, Exumas, and I spent less than $2,500; I could’ve spent much less if I knew how to catch a fish.

Richard acquired our uncle’s boat four years ago when a bad back kept Uncle John from enjoying his creation. Richard lost sight of land soon thereafter. Like many cruisers, Richard lives on his boat, which gives him countless opportunities to tackle new projects and perfect maintenance techniques. Not only does this save money; his wisdom also becomes immediately advantageous in the cruising realm. His familiarity with Margarita provided him with numerous quick fixes and temporary “solutions” that were much appreciated by his less-knowledgeable brother.

Three years ago, Richard took Margarita on his first and thus far longest cruise with an experienced friend, Jim Hamilton. Richard knew that the best way to learn how to captain his boat was to put many miles behind him, so he traveled with neither a destination nor a return date. Instead, he sailed on until his return date was chosen for him, which happened when Margarita’s single-cylinder Ducati conked out. Because Richard and Jim were both unfamiliar with the temperamental engine, they were forced to sail without the aid of a motor straight from the Rio Dulce, in Guatemala, to Isla Mujeres, on Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, then immediately set off on a straight shot to Wrightsville Beach, North Carolina. Needless to say, Richard gained a fair amount of experience on that trip, and he’s sailed thousands of offshore miles since.

Jim himself purchased a 29-foot Ericson in August 2004, when he was 24 years old, which he renamed Mojo. This wasn’t a purchase that he’d planned to make, but when his father informed him that the local yacht brokerage had an old sailboat for sale with a $3,000 price tag, he was intrigued. Despite the fact that the boat was dismasted, lying on its side, and had grass growing in the cockpit, Jim knew this was a deal he couldn’t pass up. After talking the owner down to $2,500, Jim needed only a small loan from his mother to consummate the deal. After one month of weekend work, the boat was cleaned, fully assembled, and floating near Jim’s house. Miraculously, the engine started right up, and it’s required only minor repair since.

Last year, Jim took Mojo to the Dominican Republic with the help of his friends Justin Dent and Jason Bellows. Since they all have very charitable spirits as well as light wallets, they raised money through the March of Dimes organization, under the program they named Boating for Babies. They raised $8,000, half of which went to the March of Dimes. The other $4,000 helped take some of the financial burden off their ever-tanning shoulders. They spent four months at sea exploring a significant portion of the Bahamas and the Dominican Republic. Jim currently works as a chef in Richmond, but he’s always ready to set off on another adventure.

Ian Geeson graduated from Virginia’s James Madison University in May 2003. Intent on owning his own craft, he moved back in with his parents in Wicomico Church, Virginia, and taught earth science at the local high school. A year later, with the help of a small loan from his father, he was able to buy a 32-foot O’Day for $12,000. He renamed the vessel Uhuru, the Swahili word for “freedom,” and began familiarizing himself with his new home away from home. The farthest that Ian had traveled on Uhuru until recently was Norfolk, Virginia, which is about 100 miles north of Wicomico Church, though his sailing career began at age 10, when he crewed aboard his father’s boat on a trip to the Bahamas. He’s spent uncountable hours on the water since, and after completing a captain’s course, Ian was fully prepared for an extended journey.

Despite the fact that Ian is the youngest captain in our group, he planned the most extensive ocean trial for his new boat. On June 11, 2006, one day after his 25th birthday, he left Wrightsville Beach aboard Uhuru and headed for the Turks and Caicos. From there, he and two mates planned to race straight to Jamaica for a quick break before darting to Bocas del Toro, Panama. As things turned out, Ian ended up sailing straight to Bermuda, then down to St. Croix, in the U.S. Virgin Islands, where he currently lives. He’s surfing in between shifts of waiting tables to fill the cruising kitty, and he plans to set sail soon for Jamaica and then Panama.

Jack Geier, the self-proclaimed patriarch of our young-sailor movement, also learned how to sail at a young age. His title’s appropriate, however, not only because of his early introduction to the sailing lifestyle but also because he was the first of the group to buy his own boat. In December 2002, at the age of 23, he purchased Spindrift, a 36-foot Cal Offshore, for $15,000. Then he immediately invested $10,000 more in countless improvements.

After making the necessary upgrades to Spindrift, Jack and longtime friend Davy Nichols headed south around the same time in 2003 as Richard and Jim did on Margarita. The four cruised together as planned until Florida, then Jack and Davy headed east toward the Bahamas, making it as far as Rum Cay. From there, the duo on Spindrift decided to jump to northeast Cuba, a destination that’s often not visited by U.S. citizens because it’s illegal for Americans to stop there. They landed in Bahia de Vita, sailed west until Varadero, and from there once again pointed north and headed home. It should be noted that it was merely their desire for hot showers and home-cooked meals that drove Jack and Davy away from Cuba. And now, with a new crew on Spindrift-Meredith Wike, Jack’s fiancee, and Silas and Finn, his dogs-Jack’s headed to Panama, where he’ll meet Ian on Uhuru and begin the difficult process of deciding where to go next.

All of my sailing friends embody the desire to explore new waters, an essential aspect of the cruising lifestyle. Our boundless energy, when mixed with our occasional impatience, requires us to remain in a state of constant motion, always searching for the next hot spot. Without the years of occupational servitude and responsibility, our spirits are free to travel with reckless abandon, and we learn as we go. While this may sound dangerous and unnecessarily irresponsible, we hold a clean record, with no others damaged and only minor damage to ourselves.

Sure, we’ve made-and still make-silly and even slightly hazardous mistakes. Running aground, misreading charts, and running out of fuel are common occurrences on our vessels. Towing one’s sailboat down 250 miles of the Intracoastal Waterway with the boat’s dinghy, instead of stopping to repair the engine; drying out while waiting for high tide in Charleston; setting oneself afire with cooking fuel-yep, these have all been part of the group’s learning curve. Anchor lines break due to insufficient chafe gear, sails and bags go overboard when improperly lashed, and sails rip in excessive winds. These things happen to the best of us, but we hope only once. We’re merely trying to make our embarrassing mistakes before age and experience suggest that we ought to know better. So if you see a youthful group of voyagers in need, offer them a hand or, even better, a cold beer. They can always use a break.

Michael Larkum lives in Richmond, Virginia, and works as a corporate paralegal. A picture of a white-sand beach in the Bahamas sits next to his computer, and it constantly distracts him from his work.