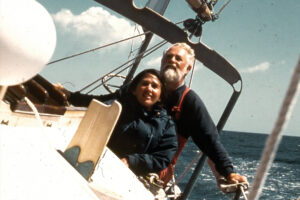

The grand, unspoiled scenery of the high latitudes lures more and more yachts to places like Labrador, the Canadian Arctic, Greenland, Svalbard and Iceland. South of the equator, it’s the Chilean Channels, Antarctic and South Georgia. Whatever the destination, a well-built, strongly rigged sailboat designed for bluewater can get to these seemingly faraway places in time to cruise through the summer season and then escape before winter gales arrive. Still, even the most seaworthy of boats must prepare for seriously cold climates and water cold enough to maintain ice, both factors on our minds when my wife, Nancy, and I modified our Mason 44, Frances B, for several summers in Labrador and Greenland.

Keeping Warm

A reliable cabin heater is the first equipment to install. A diesel heater that works with a gravity-fed fuel supply has the appeal of simplicity and easy installation. We were choosing between a Sig Marine model and a Norwegian Refleks, both sold in the U.S. by Maine’s Hamilton Marine. The Sig 170 fit our available cabin space. We had an 8-gallon aluminum tank made, which we installed 4 feet above the heater. Plumbed with a shut-off valve and a filter, it’s now been silently working for four years, eliminating the need to run another fuel line and pump from the main fuel tank. In addition to the usual exhaust pipe, we also put in a pipe to draw air from outside. This balanced setup helps maintain a draft in strong winds, and you don’t have to worry about becoming asphyxiated from the heater using all of the oxygen in the closed crew quarters. Many high-latitude yachts carry bus heaters that circulate air warmed by the engine. They consume a lot of DC current but work great when powering. On Frances B, we decided we’d rather layer on more clothing than tear up joinery for the installation of a duct/blower assembly. For the same reason, we rejected electronically managed diesel-burning units that employ ducts and power-hungry pumps. As for the less efficient solid-fuel heaters, we lacked space to load wood, coal or charcoal briquettes. And forget finding wood north of the tree line. A propane heater would present the challenge of installing absolutely leakproof piping throughout the cabin, so that got a thumbs-down too.

Keeping warm on board also relies on the consumption of hot coffee, tea, soups and stews. Our use of propane in the galley skyrockets. We take off for Greenland and Labrador with five 15-pound propane bottles. These typically last from Baddeck, Nova Scotia, through a voyage to Greenland and back to Newfoundland — not quite five months. It’s difficult to refill propane bottles in Labrador, and shops refuse to exchange bottles not previously bought from them. Greenland uses European-style fittings, so it’s best to carry enough of your own bottles.

Keeping warm on deck in windy weather is easy in these days of modern, light gear for outdoor activities. Very protective but pricey drysuits marketed by Musto, Kokatat, Neil Pryde, Ocean Rodeo and others keep you absolutely dry and don’t hinder physical activity on deck. With some layers of fleecy underclothes, however, modern offshore foul-weather gear will be quite adequate even in Davis Strait or Baffin Bay, between Greenland and the Canadian Arctic. Make sure to get foam- or fleece-lined boots, big and loose outer gloves with space for inserts, a fleece neck gaiter and several hats that lower over the ears.

We have immersion suits aboard too. They are awkward to don and restrict movement, but they may still come in handy if it comes to abandoning the boat at sea or wrecking on rocky shores. The latest immersion suit design, Stearns’ I950 Thermashield 24+, circulates the wearer’s warm breath and provides cold-water protection for over 24 hours.

Stop Condensation

Condensation is a real problem in colder weather, and not just in high latitudes. Our Mason 44 came with insulation in all lockers. It’s thin, and we have been adding layers so it’s now three-thick. On a new construction, one should line the hull with up to 4 inches of insulating material, especially for boats planning to winter in ice. Overhead hatches can rain condensation, so Nancy, ever inventive, has sewn some insulating pads — canvas pockets filled with 1-inch-thick medium-density foam. They sit against the hatch lens and are supported by mosquito-net frames. These pads block out light, which we found helpful when sleeping during the 24 hours of sunlight in Greenland, and really help stop the drips. Deckhouse portholes sweat condensation as well. I was able to stop this with Lexan storm covers I installed over the portholes as protection against damaging waves.

Condensation can also accumulate in the fuel in the integral tanks often found on metal boats. Preventing water from overcoming the fuel filter’s capacity is essential. Take fuel samples from the bottom of the tank and use a water-detecting paste on a stick or electronic sensor to determine if water is in your fuel. Installing larger filter sizes and changing them more often helps. In the super-cold waters of Antarctica, Svalbard and the Canadian Arctic, the sea can get cold enough for diesel fuel to begin congealing. Carry a supply of winter fuel additives and octane boosters. It is also good to have a separate fuel tank in a warm engine space. In Greenland, fuel suitable for local conditions and season can be bought in every village. In Labrador, where you may be sold heating diesel, the fishermen add a quart of automatic transmission fluid per 55-gallon drum to increase lubricity. I add Opti-Lube XPD, which I purchase online.

Ice Ahead!

One of the best ways to prevent trouble is to prepare the boat for the ice you will surely encounter while voyaging in the high latitudes. A propeller working in an aperture behind a keel or rudder skeg is a lot less likely to foul than a prop on a shaft held by a strut. Apart from getting fouled, an exposed prop can get damaged by chunks of ice when powering through even light brash ice. For navigating in heavy ice, a protective cage around the propeller helps. Rudders are also vulnerable, and going into icy waters with a spade rudder is plain crazy. Boats exploring ice-prone waters like Melville Bay in northwest Greenland, the Northwest Passage, or Antarctica sometimes install another skeg aft of the rudder to protect it when going in reverse. Any boat that may encounter ice, even occasionally, should carry ice poles, also known as tuks, that are 15 feet or so long; a metal blade at the end can be useful when pushing off threatening floes. That said, some boats with rudders and propellers ill-designed for coping with ice survive and have made it even through the Northwest Passage. Some people are just plain lucky.

Because chunks of ice are common in high-latitude waters, good visibility from the cockpit is essential. On Frances B we can lower the dodger when the wind is down to see better. If the wind picks up, whitecaps may mask the smaller pieces of ice. In some circumstances, one may have to heave to, as the radar picks up only icebergs and, in a flat sea, very large bergy bits. Dense fog also forces heaving to in an area with low-lying ice. The state of the sea will decide this for you.

Keep the Ocean Out

Install a valve to shut off the exhaust system to prevent flooding the engine with following seas. In extreme conditions, the boat may pitch the bow down so much that water can run from the lift box into the engine block. Few boats have a valve between the mixing elbow and the muffler lift box, but the box may have a drain valve already installed that can be used to empty it into the bilge. Heavy following seas may climb aboard, so the companionway hatch has to have storm protection covers. Cockpit drains must be effective and large — preferably two drains with a 2-inch diameter or four with a 1 1⁄2-inch diameter. Water is heavy, and on our boat I had to glass in two stout partial bulkheads under the cockpit sole to shore up the cockpit well, as it was originally supported only at the ends.

Anchoring

Generally, anchorages in high latitudes are very deep. On Frances B, we carry 400 feet of 3⁄8-inch G4 chain, the longest uninterrupted length you can buy, and it’s about right. We also have two 600-foot nylon anchor rodes. Most of the time, our Bruce anchor works very well. For particularly weedy bottoms, frequently found in Labrador at depths less than 40 feet and in the Chilean channels near Cape Horn, Frances B carries a heavy Northill anchor. An aluminum Fortress and a folding fisherman-style anchor complement our inventory.

Keep Safety Top of Mind

In August 2014, south of Greenland, the eye of Hurricane Cristobal caught up with Trevor Robertson in his 35-foot Wylo II, Iron Bark. Trevor set the Aries windvane to steer the boat with the wind on the port quarter; for the next 10 hours, venturing on deck would be suicidal. As a Cruising Club of America Blue Water Medal recipient who has spent years sailing in the extreme high latitudes, wintering in Antarctica and Greenland, Trevor certainly prepared his boat well. He reported that loose items and lockers on Iron Bark were positively secured and nothing came adrift. That must mean that his usual supply of rum in jerry jugs also survived to continue keeping the skipper warm.

Tom Zydler is a frequent CW contributor.