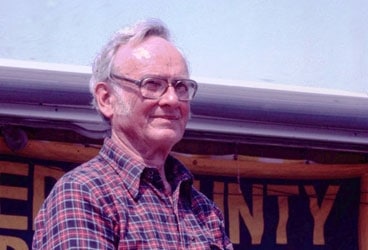

marvin creamer 368

Depending on when you pick up your June issue of Cruising World, you may or may not have time to make plans to attend the afternoon celebration that Ralph Harvey and Phillip Miller are planning for May 17 at Red Bank Battlefield National Park, along the shores of the Delaware River in New Jersey. Chances are good, though, that their friend and the man of the hour, 93-year-old Marvin Creamer, will be on hand, just as he was 25 years earlier when he and his crew dropped anchor there, having just sailed his 35-foot steel-hulled cutter Globe Star around the world without using a single navigational instrument-no compass, no sextant, no electronics, not even a wristwatch. (See www.cruisingworld.com/0906creamer for photos and event details.)

The voyage began 17 months earlier on a cold December day when Creamer and crew left Cape May, New Jersey, bound for Cape Town, South Africa. His landfalls would include Tasmania, Australia, New Zealand, and, after rounding Cape Horn, the Falkland Islands before he arrived home in New Jersey some 30,000 miles later.

Creamer was a geography professor at New Jersey’s Glassboro State College who retired in 1977. He was intrigued by such voyagers as the Vikings and the Phoenicians, who used their eyes and know-how to observe wind and waves so they could cross oceans. By the early 1970s, he decided to delve deeper into this fascination, and he answered the cruising itch by buying a 30-foot ketch that he sailed from Cape May to the Azores and back. It was during long night watches that he found that he could steer quite well by watching Polaris rather than the compass. In three more Atlantic crossings by 1980, he honed his ability to determine latitude by relying on the Pole Star and longitude based on dead reckoning.

The ketch was replaced soon enough by Globe Star, and plans were made for the record-setting circumnavigation. After completing his journey, Creamer wrote several stories for CW. In one from November 1985, “Surmounting Cape Horn,” he describes the crew’s storm-wracked start from Hobart, Tasmania, bound for Valparaiso, Chile. He recounts sailing eastward, noting that clearing the Horn was “a necessity” but “seeing it was highly desirable.” As they approached the tip of South America, he reasoned, “We could find the required latitude by noting the intensity of the twilight at the time of the December solstice. If we were far enough south to clear the cape, the sun would set, twilight would occur, and the sun would rise.”

Though they sailed through the Roaring 40s and severe weather with a broken tiller and badly damaged steering vane, Creamer describes the sail as “a jolly romp on the ocean.” Once safely home, when he reviewed position signals that the crew broadcast daily to the ARGOS satellite system to allay coast guard safety concerns, he found that after sailing 3,874 miles from New Zealand, their latitude as they approached the Horn was off by only seven miles and their longitude, which they’d based on wind and speed observations, was misstated by just 110 miles.

These days, we sail in a cocoon of electronics. Where Creamer and his crew looked for changing wave patterns, sea life, and water color to foretell land, we monitor plotters and fuel gauges and hope that the battery bank remains charged long enough to get us where we’re going. And still, it’s easy to get lost out there.

So on May 17, even if you can’t make it to New Jersey, raise a toast to a remarkable journey. Reaching a far harbor is always a challenge, but even 25 years later, doing it Marvin Creamer-style is worth noting.

Mark Pillsbury

For more on Marvin’s circumnavigation, and his future publications see his site www.globestar.org