I’m shocked. Literally. No one warned me about the most dangerous part of circumnavigating, and I’m not prepared. In fact, I feel like I’m alone and friendless in uncharted waters. Even Carolyn, my wonderful wife, lover, and navigator of 35 years, can’t seem to reach me. I’m drowning.

But let’s start at the beginning: A decade or so ago, I was racing Lasers at the St. Thomas Yacht Club when it felt like an elephant stepped on my chest. The pain was so intense that it jackknifed me off the boat and into the water. One foot tangled in my hiking strap, I was underwater, I couldn’t breathe, and my eyes were open. Time floated. Two thoughts danced slowly through my brain: One of them was “I’m dying.” The other was “Damn, there goes my boat speed!”

I forced myself to relax. I untangled my foot, surfaced, and crawled back on the boat. I stayed facedown for a long, long time and shook like a leaf. I was terrified. But in all my life, I’ve never failed to finish a race. Finishing is important to me. I’m goal oriented. I slowly sat up, sheeted in, and continued on.

Back at the yacht club, Henry Menin–who’ll sit as a juror at the 2007 America’s Cup in Spain–came up to me and asked, “Are you OK, Fatty?”

“Yeah. I had a little problem out there on the racecourse, but I think I’ll be more competitive at the bar!”

Silly me. A few days later, I was evacuated by air to a cardiac unit in Puerto Rico. As they wheeled me down the corridor, I thought, “This can’t be happening. I can’t be dying. I haven’t sailed around the world yet, and I haven’t written the big book!”

I’d never realized it before, but those were the two givens in my life: I’d circumnavigate, and someday I’d write a book worth reading. (I’ve written five books, but alas, I reckon only one, Chasing the Horizon, merits serious attention.)

Things looked bleak at that point. For the first time in my life, my horizons were shrinking. But just before dawn is always the darkest time. The test results were surprisingly good: I hadn’t had a major heart attack–just a severe cardiac wake-up call. I’d have to radically change my lifestyle, but with proper diet, regular exercise, and the right medication, I’d survive.

“How are you?” Carolyn asked nervously as I tied up my dinghy painter to Wild Card, our 38-foot S&S-designed Hughes 38.

“I’m OK. And I want to sail around the world ASAP.”

Confession: I’m not a very good sailor. I’m not a very good ship’s husband. Hell, I’m not much of a shoreside wage-earner, either. But I do have some small talents and abilities. Moving watercraft a couple of hundred miles downwind is one of them.

We left in the spring of 2000. I didn’t hedge my bets and pretend that I wasn’t sailing all the way around the world–I was up front and honest.

“I’m sailing around the world,” I told people. “We’re off on the Big Fat Circle!”

I’d even presumptuously “taken” my weekly St. Thomas radio show (broadcast on Radio One, WVWI-AM 1000) along with me and renamed it “The Circumnavigator’s Report.” (It’s currently in its 15th year, and I’ve never missed a show or been a nanosecond late.)

The moment we set off, I felt truly good. I had a goal, and it was clear, understandable, and unambiguous. True, it was very complicated, but it was also achievable.

I’d keep the boat above the surface. I’d force enough money to dribble out of my pen to survive. And, occasionally, I’d pry Wild Card out of a harbor and drift downwind to a different locale.

“Check, check, check!” I laughed as I ticked them off my list.

Everything else faded, even the face of my mother. America dimmed. My daughter’s e-mails seemed, well, interesting but increasingly mundane. I’d listen to the news on the BBC and think, “They’re all insane!”

We, however, weren’t insane. We were lit up. We were turned on, tuned in, and had truly dropped out. We’d finally become what I’d always hoped we’d be: sea gypsies. Citizens of the world. “Sailors sans frontiers,” as the French say.

It’s difficult to explain how each ocean mile seemed to empower me. I was finally in tune with Mother Nature (or, more properly, Mother Ocean). My home, my art, my profession, my transportation, my hobby, and my sport had all melded into one 38-foot watery sphere. My diet of fish, rice, and beans agreed not only with me but also with my cardiologist.

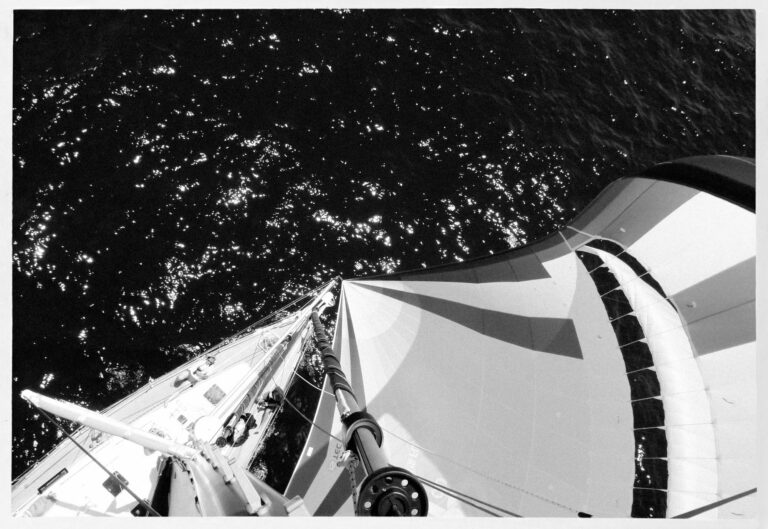

The sky seemed so big, the ocean so blue, and Carolyn more beautiful than ever. I saw God on the face of every ocean wave. My rig hummed a celestial tune; its tattered halyards tattooed ancient, wind-borne rhythms. I surged with raw passion and gladly kissed each new day full on the lips.

The Panama Canal flashed by. A blue-footed booby landed on our bow pulpit off the Galápagos. In the Marquesas, the waterfall on Fatu Hiva was icy cold. A perfect pearl from the Tuamotus rolled aboard. I crashed-tacked in Bora-Bora’s inner lagoon, thinking the huge manta ray gliding beneath me was a reef. The 400-pound Tongan princess who served me kava was, after a few bowls, pretty cute. I asked a New Zealand farmer if he’d ever cheated on his wife, and he looked sheepish. Off Darwin, Australia, I altered course to avoid what I thought was a snarl of black poly rope in the water–as the large yellow eye of a nearly submerged saltwater croc winked at me.

Through it all I kept all the circumnavigation balls up in the air: The boat still floated, its rig was up and the keel down, and our diesel auxiliary still cranked. My radio station unexpectedly e-mailed me–not to cancel my radio show but to give me a raise. I sold every story I wrote.

I could do no wrong.

Then came the Indian Ocean. I gulped it all in: the food of Thailand, the stench of India, the pristine state of the Maldives. Then Chagos: so empty of people and so full of life. It was everything I wanted–had ever wanted, really–within a 50-mile radius of deep ocean. Everything I wanted and yet, thankfully, nothing more.

There was the madness of moody Madagascar, the awful racism of South Africa, lovely St. Helena, and then home.

I honestly thought that crossing my wake and finally becoming a full-fledged, honest-to-God circumnavigator would be orgasmically cool. But it wasn’t. It was just the beginning of a strange sort of emptiness.

There seemed to be a hole in my soul.

For four years there’d been a sort of radar screen in my brain that constantly monitored the progress of the circumnavigation. I’d glance at it many times a day, often many times a minute. The challenge of circumnavigating, especially on a modest production boat with little money, was immense. I had to accomplish it in tiny bites, with a large series of cautious baby steps. It took a lot of planning, a lot of monitoring, and many incremental, intermediate waypoints. And each mile traveled, each dollar earned, and every boat-maintenance project completed brought us closer to our goal.

Now the radar screen was blank, just an irritating screech of white noise where recently my life goal had glowed so magnificently. We’d just experienced the world’s best vacation–and now I was suddenly and unexpectedly experiencing the world’s worst case of post-vacation blues.

I could write a book about every place we stopped: how friendly the Polynesians are, how sweet the gentle Balinese, how gracious the smiling people of Thailand. How could I have ever been so foolish as to leave the Land of Smiles? How long would it take to sail back to Borneo and its orangutan-inhabited rain forests? To Madagascar and its leaping lemurs? To Africa and its naked, smiling drummers?

I’d felt so alive! As if life itself were a sensuous, delicious electricity caressing my body, as if my tiller weren’t merely a stick but a magic wand connecting me directly to Mother Ocean. How can I explain what surfing atop the breaking crest of a 30-foot ocean wave feels like or watching a barometer finally tick upward as a major gale passes overhead? Or how it feels to be snatched off your foredeck by a flailing genoa sheet?

Even the worst moments of our circumnavigation were riveting: the pursuit by pirates in the Strait of Malacca, hitting Australia’s Great Barrier Reef, being surrounded–at night on the dinghy dock–by violent thugs in Southeast Asia. I remember crying when we left India.

Why?

In many ways I hated India, but some of the people we met there were so wonderful, pure, and spiritual that it was like saying good-bye to living angels.

But now, with a jolt, it was back to reality. I’m an American, for better or for worse, and here I was back on U.S. soil and surrounded by dirt dwellers, shore drones, bean counters, and the dreaded suits in the executive suite.

I tuned in a local radio station. The national news came on, and I thought the lead story was a clever-but-crude parody of someone attempting to inflame anti-Islamic sentiment. I’d just spent two years being treated with dignity and respect in Islamic countries, and I was horrified by some of the things I heard in “Fortress America” upon my return.

But it wasn’t merely politics that turned me off. Consumerism seemed to have run amok while I was gone. All my friends were making massive amounts of money but living impoverished lives on every level that mattered to me. There was noise everywhere. Video screens flicked from every doorway. Cars swooshed. Trucks roared. Everything seemed to be vibrating, as if a large unseen generator running underground was about to blow a piston through its cylinder block. A Jimmy Buffett lyric ran crazily through my mind: “Where you gonna be when the volcano blows?” I felt like a modern Flying Dutchman, doomed forever to sail without touching the shores of the land of my previous culture.

I went to a bar and bought a cold beer. Snatches of conversation washed over me: “John’s new SUV has a DVD player in the back for the kids.” “So I told him, ‘I can’t live on $35 an hour,’ and he said, ‘Well, if you factor in our health insurance–.'” “Don’t the ragheads realize you can’t rule the world without learning how to use toilet paper?”

I went back to Wild Card and sat in the cockpit. Carolyn could tell at a glance I was upset. I was thinking, “I’m forever changed. These last 50,000 ocean miles have ruined me.”

Carolyn sat next to me and didn’t say anything. I felt confused, childlike, and angry. Finally, I blurted, “I want to go.”

“Go where?” she said.

“Just go.”

And with that, the crew of Wild Card went–to transit the Panama Canal for the second time.