closing the circle 368

Looking back, the highlights and lowlights seem as vivid and indelible as the snapshots in a photo album: the unforgettable (yet unsettling) glaciers in the Canal Beagle; the awful night in Chile’s Golfo de Penas; the massive, deadly earthquake off the Chilean coast; El Niño and the non-existent trade winds; diving among hammerheads in the wondrous Galapagos; the jarring Baja Bash; golden California; the Columbia River bar; and finally, downtown Seattle, right where it all began. The images from the last 9,500 nautical miles of the voyage “Around the Americas,” from Cape Horn to the Pacific Northwest, were quite different from those recorded in the 18,000 miles that preceded them.

Take, for instance, the feather.

First mate Dave Logan and I had been paddling our Little Wing carbon kayaks along the primeval northern flank of the tiny island of Cocos-a Costa Rican national park roughly 250 miles off the Central American mainland-when a pair of frigate birds, soaring on the high thermals, caught our attention. It took a moment to grasp the fact that they were playing a game of catch. One bird dropped a feather from its beak, the other wheeled around to snatch it out of the air. I realized nobody was going to believe this far-fetched tale, so I yelled over to Logan for confirmation.

“You’re watching this, right?” I called.

“I sure am,” he replied.

After a couple of rounds, they missed connections, and the long, brown feather wafted down from the sky and landed in the water precisely an arm’s length from my kayak. Astounded, I scooped it up and snapped it under the shock cord just forward of the cockpit. Up until then, most of my souvenirs of the trip had been memories and photographs, but now I had something tangible and real to show for our travels, as well as a pretty good story to go along with it. In many ways, it crystallized the entire, amazing voyage aboard our 64-foot cutter, Ocean Watch, where extraordinary things seemed to happen almost every day.

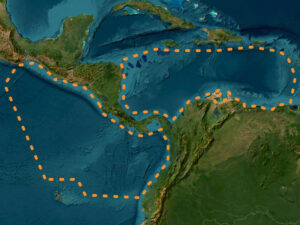

Captain Mark Schrader, who launched the Around the Americas odyssey with old sailing mates David Rockefeller Jr. and David Treadway (who in turn co-founded the ocean-conservation group Sailors for the Sea, one of the primary backers of the expedition), likes to say that when he’s confronted with a problem or challenge, he draws a circle around it. On a charter cruise through the Mediterranean several years ago, the three friends agreed that the oceans were under assault on several fronts, so Mark found a map and encircled the continents of North America and South America. Ultimately, the trio hatched the plan to circumnavigate the Americas to underscore the notions that the landmasses are one large island surrounded by a common sea and that the problems and challenges are also interconnected.

In late January, having already sailed through the Northwest Passage and down the eastern flank of both continents, Ocean Watch rounded Cape Horn and set a northerly course back to the Pacific Northwest, where the journey began on May 31, 2009. Over two-thirds of the circle was complete.

For most of the clockwise voyage, we’d been incredibly fortunate, and our luck had held at the Horn, which we negotiated under spinnaker before a rare easterly breeze. (See “Cape Horn to Starboard,” June 2010.) The skipper’s original plan had been to forge on “outside” to the Chilean city of Puerto Montt, some 400 miles to the north, but with a series of powerful gales lining up from the west, discretion overruled valor, and we altered course for the inside via the Canal Beagle and the Strait of Magellan.

Navigating the distant waters of Tierra del Fuego, Patagonia, and the Chilean channels proved to be a visually arresting, fortuitous choice-but also one that brought to light some disturbing facts. After a brief layover in the Chilean navy town of Puerto Williams, we pointed Ocean Watch west past the sprawling Argentine burg of Ushuaia, then on into the Northwest Arm of the Beagle. The primary feature of this broad waterway is called the Darwin Cordillera, a jaw-dropping range of nearly 8,000-foot mountains that’s chock-full of ventisqueros, or glaciers, such as Italia, España, and the most famous of them all, the Romanche.

As in the Arctic, where diminishing sea ice has permitted two-dozen cruising boats to traverse the Northwest Passage in recent years, the ice in the Chilean channels is changing. Of the 48 glaciers in the Southern Patagonia Ice Field, all but two are rapidly shrinking. The rapid runoff from those receding glaciers-the rivers and waterfalls that left us spellbound-are increasingly becoming an alluring prospect for dams and hydropower.

And as Ocean Watch ranged northward up the west coast of Chile, the empty inlets and coves were filled with ever-increasing frequency with enclosed, penned-in salmon farms, the “harvest” therein nourished with pellets of proteins and antibiotics that are causing pollution and infectious salmon anemia. The fish farms are the direct consequence of offshore waters that have been seriously overfished, and the bad news doesn’t end there. Seals and whales that were once in abundance have disappeared, and a red tide has ruined the formerly prosperous shellfish yield. For all its remarkable beauty, fragile, gorgeous Chile seemed, in so many ways, dauntingly at risk.

So the last thing the good people of Chile needed was a deadly, 8.8-magnitude earthquake. As far as the quake was concerned, again, our well of good fortune aboard Ocean Watch was overflowing.

After enduring a thrashing in the notorious Golfo de Penas, an open body of water renowned for its relentlessly foul disposition-its short, nasty, bottomless cross-seas coupled with gale-force winds made for probably the worst stomach-turning night of the entire expedition-we were rewarded with a benign run up to Puerto Montt. Next was a fast, lovely, 550-nautical-mile passage before brisk southerlies to the bustling Chilean city of Valparaiso, where my old sailing mate Mauricio Ojeda had secured us a berth in the smart little basin of the Club de Yates Higuerillas, in the nearby resort village of Concon.

Following a relaxing, enjoyable week in “Valpo” to recharge the figurative batteries after 4,000 hard miles from Mar del Plata, Argentina, we set sail for the 1,300-nautical-mile journey to Lima, Peru. On the last day of February, some 72 hours later, the inbox for our satellite-based email accounts was besieged with queries: Were we still in Chile? Was everyone OK? Did Ocean Watch weather the tsunami?

Though we were still off the coast of Chile, it was the first we’d heard about the quake.

In the aftermath of an earthquake, tsunamis race across the ocean floor with enormous force and energy, and the one that spun off the devastating Chilean temblor shot across the deep Pacific basin at hundreds of miles per hour. It’s when those depths grow shallow, along coastlines and islands, and all that undersea inertia reaches the end of the runway with nowhere left to go, that tsunamis become lethal. At the surface of the vast ocean, however, many miles offshore, Ocean Watch sailed safely on.

One of the first emails we received came from our friend Mauricio, still in Valparaiso: “Ocean Watch was lucky to sail. We had troubles at the club. Although there was not a violent tsunami in our area, the sea completely receded after the earthquake, drying out the marina. Boats lay on the bottom, high and dry. When the sea slowly came back, the level reached an altitude much higher than normal, by eight feet. Most of the boats floated again, but three yachts were sunk. Piers were affected. But our problems at the club are only of material costs. No casualties.”

Would the steel, 44-ton Ocean Watch have picked herself up off the ocean floor and survived the grounding? We’ll never know. Once again, all we could do was invoke one of our recurring themes: Just how lucky could we get?

Once in Peru, we anchored off the welcoming facilities of the Yacht Club Peruano, in the resort village of Callao, a short distance from the teeming city of Lima. There, as in many of our destinations, we welcomed hundreds of school kids aboard to tour the boat and visit with teachers and staff from Seattle’s Pacific Science Center, the expedition’s other primary supporter. As always, the bright, curious, engaging students-who seem to understand more about the threats to our oceans than we adults, the creators of those threats-left us cautiously hopeful about the future.

In mid-March, we pushed on for the Galapagos archipelago. According to the pilot charts, in normal years, steady easterly trade winds would fuel the trip from Peru on to the equator. But the strong 2010 El Niño effectively switched off the trades as well as the usual coastal upwelling and northerly currents that generally prevail off the upper flank of western South America. With calm seas and water temperatures nearing 90 degrees F, what should’ve been a sweet sail turned into an uneventful delivery trip almost exclusively under power. The main diversion was hacking away the discarded longline fishing gear we wrapped around the propeller about midway through.

The last time I sailed into Puerto Ayora, also called Academy Bay, the main harbor on Isla Santa Cruz in the heart of the Galapagos isles, was about 15 years ago; at the time, you could count the number of dive boats and small cruise ships on one hand. Back then, the restrictions on cruising sailors imposed by the Ecuadoran government were rigid, so it was also rare to see a private yacht rambling about the islands.

So when Ocean Watch motored into the bay in the early hours of March 22, I was stunned to see not only dozens of craft catering to the tourism trade but also a huge fleet of cruising boats as well, many of them on a Pacific rally sponsored by a U.K. sailing magazine.

In Puerto Ayora, we met Stuart Banks, an oceanographer at the Charles Darwin Research Station who’s lived and worked in the islands for nearly a decade. He confirmed the fact that things were certainly more hectic than they used to be.

“Fifty years ago, there was hardly anybody here,” he said. “In 1960, there were 4,000 visitors. Now we get between 140,000 and 160,000 tourists a year. In the last 10 years, there’s been an increase of 14 percent every year. It’s one of the greatest increases anywhere, and that kind of pushes everything else.”

With the growing numbers of ecotourists and a corresponding influx of native Ecuadorans who’ve moved to the islands to provide goods and services, the delicate balance of this destination is being challenged as never before. Bleached and damaged coral-some of it the result of poor anchoring practices-that photographer David Thoreson and I witnessed on a series of scuba dives, is one byproduct of the ever-growing traffic.

But of course, along with the famous birds and reptiles roaming among the islands, the world-class diving there was exquisite. Divers like us flock to the islands in droves to interact with big animals: surprisingly graceful sea turtles; playful sea lions, as giddy as puppies; and majestic rays, including mantas, as wide and arresting flying beneath the seas as the albatross that soar above them.

And that’s not counting the grunts and wrasses and snappers and idols and grouper and barracuda and parrotfish and, of course, the sharks: white- and black-tipped reef sharks. Galapagos sharks. Hammerheads. It’s easy to see why so many people want to experience the Galapagos. But as in so many other places, in so many ways, it begs the question: Are we loving our oceans to death?

From the Galapagos, we pushed forth to Cocos Island, where I picked up my feather, and then paid a call on Costa Rica, a magical place of rain forests, volcanoes, glorious beaches, and some of the friendliest people on the planet. The plan had been to push on from there directly to Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, but the placid El Niño conditions persevered, and we were forced to call in Acapulco (poor us!) to top off the fuel tanks. The trip up to P.V. was equally non-eventful, but the onward leg to Cabo San Lucas, and up the coast of Baja California, was a jarring, miserable thrash to weather in staunch northerly winds. They don’t call it the Baja Bash for nothing.

As we neared the border town of Tijuana and then put it behind us, there was a big reward at the end of the upwind grind. On May 4, a little over six months since the Miami skyline faded behind us, we were back in the U.S.A.

Among the friends and supporters to greet us at the dock of the San Diego Maritime Museum was Hall of Fame basketball great Bill Walton, a native San Diegan who’d gotten wind of our story and had been following our progress. It was all quite a welcoming.

It was also bittersweet. Two weeks earlier, the BP oilrig explosion in the Gulf of Mexico unleashed one of history’s all-time environmental catastrophes. One morning in Ocean Watch’s cockpit, with the morning’s New York Times in hand, I looked up from a picture of dead pelicans and noticed the frigate-bird feather from Cocos Island, which I’d tucked in a crack of the pilothouse ceiling.

It all made me feel rather ill.

The accompanying story was about the potential reach of the spill in the event of a hurricane or if it drifted into the Gulf Stream, and the account went to the very heart of the message we’d been trying to convey. We are indeed “one island, one ocean,” and what happens in any one place ultimately affects us all. For heaven’s sake, will we never, ever learn?

Another bone-jarring series of hops up the coast of California in the teeth of more serious northerlies (with stops in Marina del Rey, Santa Barbara, Monterey, and under the Golden Gate Bridge to San Francisco) was like watching a boring sequel to the bad movie we’d endured off Baja. We caught a break on the run up to Portland, Oregon, via the Columbia River Bar, which we transited on the calmest afternoon possible. But fittingly, after a short layover in hip Portland, on the trip’s last offshore hop along the coast of Washington state, we had one long, bumpy, miserable night at sea.

Then, remarkably, on the afternoon of June 14, the wind and waves lay down, and there before us was Cape Flattery and the lighthouse on Tatoosh Island. We were back at the beginning.

It would be another couple of days before we finally tied up in Seattle, after 382 days and 51 port calls (along with dozens of nights in quiet anchorages), and with 27,524 miles on the trip log. On that very last day, we returned to Shilshole Marina from Port Townsend after picking up a boatload of the scientists, teachers, family members, and friends who’d accompanied us on separate legs of the trip. For everyone involved, it had been a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

But the vision of Cape Flattery really signaled the end of the voyage. Our core crew-skipper Schrader, mate Logan, photographer Thoreson, oceanographer Michael Reynolds (who’d been aboard for most of the adventure), and me-wandered up on the foredeck for pictures, and moments later, Ocean Watch sailed out of the Pacific swells and into the protected waters of Neah Bay.

It was hard to believe, but true. The circle around the Americas was closed.

Herb McCormick is a Cruising World editor at large.