I happen to know several sailors who do not like night sailing, having done too much of it already. They do not like the hardships of ocean racing in a sport that is supposed to be a pleasure. . . . What they want is to sail in the daytime in pleasant weather and sail fast enough to get the sensation of sailing. The only thing that will satiate the desire of these men is the sailing machine, and they should be allowed to have it.

L. Francis Herreshoff, creator of such pure sailing vessels as the H-28, the Rozinante canoe yawl, and the ketch Ticonderoga, wrote these words in 1946. Nearly 60 years later, three boatbuilders–Morris Yachts, Friendship Yacht Company LLC, and The Hinckley Company–have taken daring steps of which, we believe, L. Francis would have heartily approved.

Responding to what they perceived to be an evolving taste among ragmen, these boatbuilders produced, in time for last fall’s boat shows, three “sailing machines” between 36 and 42 feet LOA for daysailing use. And while these three boats appear at first glance to be similar, they’re not, for their designers have employed varying concepts to achieve the same goal: a quickly rigged sailboat that’s traditional in appearance, fast, responsive, and easily sailed shorthanded.

We think L. Francis would approve of how each builder has accomplished its mission, and we’ve asked him to stand by, if only in spirit, and offer commentary as we look at the Hinckley DS42, Morris 36, and Friendship 40.

In America, the heyday of such “dayboats” may have been in the early 20th century, before World War I, when time for the privileged was of little essence and summer days stretched interminably toward the horizon. In 1906, a member of the Manhassett (New York) Yacht Club commissioned Charles D. Mower to design a schooner for day use. This would be launched as the 33-foot Pagan.

Her owner had requested a fast, nimble vessel with an easily handled rig–the schooner rig broke up the 616-square-foot sail plan into manageable bits of canvas–and a minimal cabin in which to seek refuge from cold, wind, and rain and for sleeping on the occasional over-nighter. Together, the clear decks and low coachroofs, required for excellent visibility and crew mobility in tight quarters, and the large cockpits, conducive to family and social outings, left little space belowdecks. The truly lightweight (5,836-pound displacement) Pagan spawned a class of similar schooners–the New Long Island Sound class–that were 41 feet in overall length, 30 feet on the waterline.

In 1907, B.B. Crowninshield, who designed fishing schooners as well as America’s Cup contenders, drew the lines for a 36-foot-three-inch schooner-rigged dayboat, with 616 square feet of sail, for his personal use. “I wanted the biggest and fastest boat I could handle comfortably alone,” he wrote, “one that would lie nicely at a mooring with the mainsail set, be a good sea boat, and be capable of comfortably holding three in the cockpit.”

Crowninshield later refined his prototype dayboat in the form of the 40-foot schooner Fame, whose lines were much influenced by those of the fast, seaworthy, and seakindly commercial vessels that came off his board. Pagan and Fame had 4:1 and 5:1 length-to-beam ratios, respectively, which provided hulls that pushed less water than wider designs.

Fame had a light displacement for her length and construction, yet her tiny cabin, with its four-foot-six-inch headroom, still had room for settees port and starboard, a pipe berth in the forepeak, and lockers for clothing, tools, and utensils. Fame spread 757 square feet of sail.

As you pore over these three daysailers of the new millennium–in an era when time has become a precious commodity–note the many similarities between their forms and specifications and those of their predecessors of a century earlier: long overhangs, moderate drafts, minimal accommodations, and modest, easily managed sail areas. Two of the three dayboats, the Hinckley and the Morris, are, by today’s standards, narrow of beam. To the casual observer, whose idea of a daysailer is the Uffa Fox-designed 17-foot O’Day Daysailer, all three seem much too long for dedicated day use.

Perhaps it would be well now to consider some of the speed-giving qualities a sailing machine must possess to acquire speed. . . . Length is what the sailing machine must have if she wants to go fast.

The Hinckley DS42, the Morris 36, and the Friendship 40 have long and distinguished individual lineages, and the evolution that’s brought them into the electronic age of sail seems natural, logical, and sensible, three words that could have been Mr. Herreshoff’s mantra as he practiced his architectural artistry. In the pages ahead, with L. Francis along to observe, we step aboard this fancy trio of 21st-century daysailers.

The Sailor’s Picnic Boat

The beautiful yacht may not be the fastest, but my experience is, like the beautiful woman, she usually is.

The Hinckley DS42, with her 13 feet of overhangs, is stunningly beautiful–which we’d expect of a Bruce King design–and hull number one, Last Chance, sailed like a witch on a raw, blustery fall day on Chesapeake Bay, when the wind gusted over 15 knots. It seems natural to lead off with the Hinckley offering, for The Hinckley Company, in the early 1990s, was the first to tap the classic dayboat market with its motorized Picnic Boats. “People told us we’d lost our minds, building a 36-foot boat that sleeps two,” said Hinckley sales director John Correa, “but we’ve built more than 300 since then.”

Lifelines are optional–with removable stanchions that screw into flush bases. Hinckley DS42 hull number two was in mid-construction last fall and about to receive a deck, while hull number three, which will have lifelines, was in the mold.

Epiphany: Hinckley began thinking about a sailing version of its popular Picnic Boat, which was introduced in 1994. “This proved to be a remarkable litmus test of a market, said Correa, “and a remarkable success.”

Concept: Hinckley intended to combine traditional elegance with state-of-the-art technology in the creation of a dayboat on which the helmsman can do everything. “You can take a nonsailing friend out on the 42, keep him away from the sheets, and both of you are happy,” Correa said.

The sailing machine would only require a crew of two. . . . She would not have to have any sails forward that would require the crew to leave the cockpit unless a spinnaker was set.

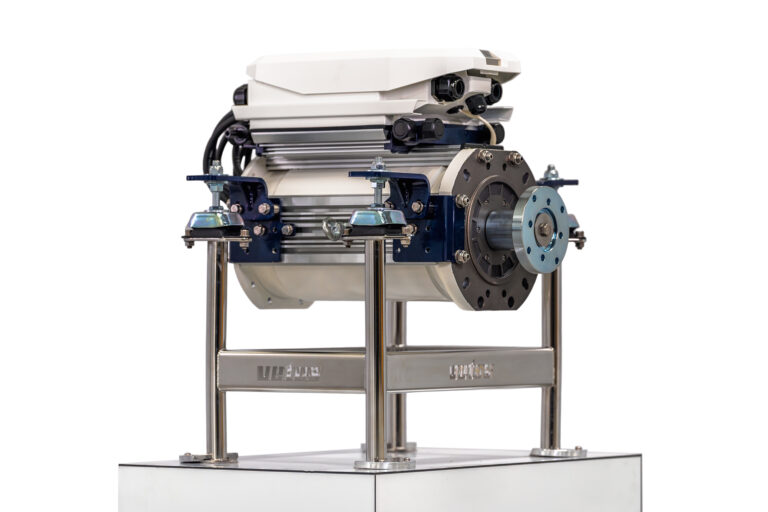

Bells, whistles: The Solomon Technologies electric “pancake” engine has a single joystick on the steering pedestal and is powered by a dozen 12-volt batteries charged by a Fischer Panda 4.5-kilowatt generator. The retractable, hydraulic, bulb-tipped fin keel rides up and down in a carbon-fiber centerboard trunk. A remote winch drive for the main halyard on a “phone cord” enables a singlehander to walk forward to monitor the raising of the full-batten, roachy North 3DL main. The Hall Spars carbon mast has a faux wood finish, as does the Leisure Furl in-boom furler. In supporting roles: rod rigging and a Vectran backstay. The jib furling drum is belowdecks; a furling line is led aft. The mainsheet is hydraulically powered. All sheets are led to pods within reach of the helmsman. The hull has a Kevlar shell and a vacuum-infused carbon-fiber inner skin.

Cockpit: The large, open cockpit seats from six to eight people, plus the helmsman on a dedicated helm seat.

Cabin: Headroom is sitting height only throughout the DS42’s cherry-ceiled interior, which, when you go below, seems to work just fine. This is a daysailer/occasional overnighter, after all.

Under the two-step companionway are switches for the DC panel, the generator, and the hydraulics. Port and starboard of the companionway are benches with storage underneath. Just forward and to starboard is the galley, which has a gimballed stove, sink, and sliding-door lockers with shelves over a fiddled counter. The water-tank gauge is below the sink.

The head, with locker and counter, is opposite the galley. The enclosed head really works, perhaps because where it matters, it meets L. Francis’ minimum “toilet-room” width of two feet six inches. All horizontal surfaces are fiddled. The forward cabin is a cozy V-berth arrangement with a cedar-lined hanging locker and three-drawer bureau.

Sea trial: As we powered away from Hinckley’s dock in Oxford, Maryland, the only proof we were motoring was our forward progress. There was no sound or vibration as the long, narrow (4.2:1 length-to-beam ratio) hull sliced through the quiet water of the harbor. John Correa throttled up. The strangely absent concurrent rise in decibels to which we’re accustomed with diesel engines emphasized how much we depend on sound to determine speed and rpm–and whether the engine is on or off. Stimulus-response betrayals aside, being propelled by an electric engine was a new and pleasant experience that seemed more compatible with and similar to harnessing the wind.

We dropped the keel and raised sail, and the transition from power to sail was seamless–no sudden, blissful elimination of noise and vibration that makes us wonder why we put up with engines in the first place. The sails filled; the wake began to sizzle off the leeward side of the long, lean hull. We couldn’t believe our eyes as the speedo read 6.8 knots through the water in 10 knots of true wind, and the slight weather helm led Last Chance onto a rail for a perfect beat.

An 18-knot gust caused the DS42 to round up, so we reefed both main and jib, and in a rising wind, her lightweight carbon mast and deep fin keel with lead bulb kept her on her bottom. With her 19.5 sail area/displacement ratio, we knew she’d be a fine light-air performer. We threw in some tacks and jibes, finding the DS42, with her foil keel and high-aspect rudder, deliciously responsive. Her pronounced sheer and high, seamanlike bulwarks left the decks dry.

The long, narrow craft has a surprising amount of stability when combined with a deep lead keel since the distance between the lead and the center of flotation is much more than in the wide, deep craft, so the difference in the lever arm more than makes the difference in

weight of the lead.

As we ghosted toward our slip at half-throttle, a bypasser stopped, did a double take, and grinned. “Bruce King has a way of making people smile,” offered Correa.

In Poppy’s Storied Wake

Many people are now talking about cabin plans for long-distance cruising, and it is a little unfortunate. I say “unfortunate” because if the cabin is really designed for long-distance cruising, it will be rather poor for coastal cruising. Just why so many people plan to go to sea in small boats is a mystery to me, for not one in almost a million has the qualifications for it.

For Cuyler Morris, president of Morris Yachts, the events of September 11, 2001, jump-started the simplicity theme. “People began to realize that they are only able to do so much in their time on the planet,” he said. “So if you’re going to have a big cruising boat that’s going to cost you a lot of money to build, sail, maintain, and store, then you’d better use it in the way it was intended.”

And Cuyler was using the M36 as it was intended this late-summer day on the Chesapeake. Leaving the dock in Eastport, Maryland, he steered her with his foot as he hauled on the main halyard, set the roller-furling jib, trimmed the sails, and participated in an animated conversation–all without moving an inch.

The principal advantage of the roller jib is that you can get under way almost instantly, which is an advantage for making early starts in the morning.

“We had a couple come aboard the M36 at the U.S. Sailboat Show, and they thought the boat was elegant and beautiful,” he said. “But they added that there wasn’t enough for them to do on it and went on their way.”

Olin Stephens, whose firm designed the 32-foot daysailer Poppy in 1965, the mahogany-on-oak sloop that inspired the M36, apparently had no such problem with the concept. “Olin was the first non-Morris to sail this boat,” he said. “At the S&S 75th Anniversary at Mystic Seaport last July, he came aboard for a sail, and he loved what we’d done.”

Morris Yachts sold hull numbers 10 and 11 at last fall’s Annapolis show, and the next available, number 12, is due for delivery this July.

Epiphany: After work, before they went home, Cuyler and his father, Tom Morris, would blue-sky about the kind of “simple dayboat” they’d like to be sailing. “We had a rough idea of what we wanted,” said Cuyler, “but nothing concrete until 2000, when we partially restored a classic wooden dayboat named Stormy–the original Poppy–which got us thinking along these lines.”

Then, last winter, fortune took over. Tom Morris traveled to Sparkman & Stephens in New York City for a signing ceremony of Olin Stephens’ book Lines: A Half-Century of Yacht Design, 1930-1980 (2002; David R. Godine, www.godine. com), and during the visit, an air-brushed drawing of design number 1765 caught his eye. He found a phone and called Cuyler, saying, “You better get down here; there’s something you ought to see at S&S.” This was a rendering of Stormy that cried out to be reincarnated in composite construction for a new market of sailors.

Concept: “We’d been tossing this concept around for about five years: a simple dayboat built of modern materials you could pile the family into, take off on a moment’s notice, and easily manage in most conditions by yourself,” said Cuyler.

Bells, whistles: The Morris 36 has a high-aspect fin keel and bulb, a carbon spade rudder, a carbon-fiber mast from Hall Spars, and optional Leisure Furl in-boom mainsail reefing. The self-tacking jib is on a curved track. Sheets and halyards are led belowdecks to control/winch pods near the helm station. Manual self-tailing winches are standard. The hull is of cored vinylester composite construction. There’s DC refrigeration for the picnic lunches and beverages.

Cockpit: The six-foot-long cockpit is capable of seating six people plus the helmsman. An icebox is under the starboard cockpit locker. Belowdecks storage is accessible through all three seat hatches.

Cabin: As with the Hinckley daysailer, the Morris has sitting headroom. The interior is fresh and cheerful–“modest,” Morris admits–with white bulkheads and overhead and bright mahogany doors, drawers, and trim.

In my opinion, headroom is not as important as some people suppose. On a small yacht at sea, you do not walk around, you slide along in a crouched position. You spend most of your time sitting or lying down, but if there is not a full six-foot headroom, it might just as well be a foot less. . . . I find most of my sailor friends like to eat sitting down and much prefer to sleep lying down.

Below the companionway, an enclosed “day head” with sink and freshwater hand pump is to port, with the galley opposite boasting sink, freshwater hand pump, and fridge. Standing headroom exists in the galley under the open companionway hatch. Moving forward, port and starboard settees offer fine pallets whereon to while away the day reading at anchor or to sleep.

If you spend the night alone in an open boat in a thunderstorm, it will do a couple of things to you–it will bring you closer to God than going to church 40 Sundays. Yes, and it will make you talk reason about cabin plans. . . . A tight deck, a dry place for some food, a berth and a lamp to read by are the main things. Sometimes the very small cabin or cuddy is the nicest.

Sea trial: It was a great fall day for sailing on the Chesapeake, with 12 knots of true wind and a flat sea. The M36 held a steady course and hinted at an easy motion when wakes from powerboats plying the Intracoastal Waterway’s magenta line broke the spell. She proved weatherly, tacking through about 80 degrees, although Cuyler said that 90 degrees wasn’t unusual in certain wind speeds and sea states: “Light and lumpy, wide tacking angles,” he said; “heavy and flat, the closest.”

In gusts, we heeled to just about the top of the cove stripe and no farther, thanks to the lightweight carbon mast and low-windage rod rigging, which enhance her stiffness. “When I first sailed her, I did a disconnect,” said Cuyler. “The M36 does everything the J/105 does, but doesn’t look like it should be able to.”

Traditionally, lifelines haven’t been part of the dayboat concept, and we asked Cuyler if buyers, in the spirit of safety at sea, had requested them. “Of the 11 hulls that have been built, two have been delivered with lifelines,” he said. “One was delivered to Ireland, where boats have to conform to European standards, and the other was sold to a family with young children.”

Birth of the Mini-Megayacht

While the beautiful woman is not the cheapest either in first or last cost, the beautiful yacht usually is much the cheapest in the end. There are several reasons for this, not the least of which is that she must invariably be designed by a talented designer, and his knowledge of construction will probably be equal to his other arts.

The Friendship 40, with a sailaway price of $804,000, is the most expensive of the three daysailers, and it is arguably the most striking. “Material cost was not a consideration,” said designer Ted Fontaine. Fontaine worked for Ted Hood at Little Harbor for 22 years, 16 of them as head of the design division. “Having seen what Ted Hood did, I learned not to be penny wise and pound foolish.”

There also was the matter of the Friendship’s New Zealand builder, Alloy Yachts. “We had to have a boat that was exquisitely built with space-shuttle specs to be simple and clean with fewer things to go wrong and fewer warranty problems,” said Fontaine. “We simply couldn’t afford to warranty a boat built in New Zealand that was going to the United States.”

Fontaine wanted to have his boat built in New Zealand, “where sailing is the national sport.” He chose Alloy Yachts because, he said, “They have good craftsmen, most of whom are sailors, and all of whom wanted the work and wanted to show what they could do.” Thus, little details appeared in the finished product: The caprail was cambered in two different directions, you won’t see one bung in the caprail or the coaming, one chock pattern was used for six different positions, and there’s trim inside the locker doors.

The builder and his workmen always take much the most interest and care in a beautiful yacht. As she takes shape, they glory in trying to add to her perfection. Her beauty seems to feed their enthusiasm. . . . The reader may not realize it, but the workmen in the shop as a class are the greatest connoisseurs of design . . . and they have the highest appreciation of the beautiful.

As of last fall, hull number one had been sold and construction of number two was under way.

Epiphany: Ted Fontaine saw a pattern he didn’t like: When sailors decide their cruising boats are too large for simple, enjoyable sailing, they usually convert to power, “and we’ve lost a sailor from our market,” he said. His plan: to design a boat for 45- to 60-year-olds that would keep them sailing and cruising.

Concept: The Friendship 40 was to be a “mini-megayacht” in performance, amenities, and quality of construction and hardware, but it was to be easily sailed by one or two. It would be modeled after the traditional Maine workboat, the Friendship sloop, with its sensuous yet functional sheer and tumblehome and characteristic oval counter stern, but it would have a centerboard and a modern carbon rig.

Bells, whistles: The Friendship 40 has Core-Cell foam-core hull construction, Leisure Furl in-boom furling, rod rigging, and a hydraulic Navtec vang and backstay adjuster. The Reckmann manual genoa furler has an under-deck reefing line led aft to a primary winch. The “virtual-tiller” wheel requires only one turn lock to lock to increase responsiveness. The mainsheet (two-speed winch), furling, and bow-thruster control buttons are at the helmsman’s feet to free up hands when sailing shorthanded. And there’s a dodger, centerboard, a microwave oven, and a full head with shower.

Cockpit: It’s large; as the Friendship folks are wont to say, “This is where you live on a dayboat.” The radius of the taffrail is picked up by the teak cockpit coaming, resulting in a graceful, sumptuous U-shaped bench (broken only by the winch consoles) that looks as if it could seat a dozen adults for cocktails or dinner. The drop-leaf table incorporates storage lockers surrounding an insulated beverage box with drain.

Cabin: Despite a low and handsome house, the cabin has full headroom below. The layout is open, without full bulkheads separating saloon and forward cabin. In fact, it could be said there’s only one large stateroom including all amenities for extended cruising, which is the Friendship’s strong suit.

The cabin is bright, cheerful, and inviting, with traditional white ceiling in the overhead and varnished raised-panel teak joiner work. The galley, with sink and microwave oven, is to port as you descend the companionway, and the full head with shower is opposite. Moving forward, settees are port and starboard with three lockers beside each. Above each settee are fiddled shelves with large lockers on either side.

In the forepeak, a double centerline berth has a pair of cushioned seats, a pair of drawers port and starboard at its foot, and lovely oval-topped lockers and fiddled shelf space on either side. Ergonomic teak grabrails frame the main part of the cabin at shoulder height, and handholds are on the abbreviated bulkhead between the living areas.

Sea trial: While the Friendship 40 will be an excellent inshore cruising boat, it retains the 360-degree helm visibility essential for a dayboat in busy harbors and tight anchorages.

We set out in 12 to 15 knots of breeze, and the broad sections required of a stable centerboard boat kept the Friendship 40 sailing upright. “I put in the first reef–between the first and second battens–in 15 to 18 knots,” said Fontaine, who added that a heavy-duty vang keeps the boom level.

If length is necessary for fast sailing, stability is an

essential for sail carrying.

Under her large mainsail and self-tacking jib, the Friendship 40 had sufficient weather helm in gusts to make me want to reef, but Fontaine told me to ease the main with my foot and spill air, which proved a far simpler solution for the shorthanded crew. “Just give the button a little tap, have about seven degrees of rudder angle, and depower the main,” he said. “It’s like steering a horse into a barn: It knows where it’s going. It just needs a little guidance.”

With a sail area/displacement ratio of 18.5, the Friendship 40 began to excel as the wind velocity increased, and the 363 displacement/length ratio was reflected in the power of the hull as it bulled its way on a rail with a very easy motion through an annoying Chesapeake chop.

Hull number one was named Manaaki. “We wanted a name with New Zealand origins, a Maori name,” Fontaine said. “Manaaki roughly means ‘to earn respect.’ I think we may have earned a little respect in this market.”

The Last Word

The Hinckley DS42, the Morris 36, and the Friendship 40 incorporate the best of the traditional with the most applicable of the cutting-edge, and their wholes are infinitely greater than the sums of their parts.

“One authority has said that good art depends principally upon persistent contemporaneousness and things that are too old style or too modern are not compatible,” wrote L. Francis Herreshoff nearly six decades ago. “No doubt the best painters have been those who were entirely familiar with past techniques and could use them when necessary. So, too, with the designer. If he can borrow things from the 18th and 19th centuries and use them correctly, he has a great advantage over those who know only present-day techniques. In the study of old . . . models, you can train the eye to recognize the beautiful.”

The three designers of these modern variations on a century-old theme did just that.

Nim Marsh is a CW contributing editor.

BOAT SPECS

Hinckley DS42

LOA 42′ 3″ (12.88 m.)

LWL 29′ 3″ (8.91 m.)

Beam 10′ 6″ (3.20 m.)

Draft (keel up/down) 4′ 0″/7′ 3″ (1.22/2.21 m.)

Sail Area 730 sq. ft. (67.81 sq. m.)

Ballast 4,800 lb. (2,182 kg.)

Displacement 14,700 lb. (6,682 kg.)

Ballast/D .33

D/L 262

SA/D 19.5

Mast Height 63′ 0″ (12.88 m.)

Auxiliary Solomon Technologies ST-37 electric motor

Designer Bruce King

Sailaway Price $735,000

The Hinckley Company

(207) 244-5531

www.hinckleyyachts.com

Morris 36

LOA 36′ 1″ (11.0 m.)

LWL 25′ 0″ (7.62 m.)

Beam 10′ 1″ (3.07 m.)

Draft (standard/shoal) 6′ 6″/5′ 3″ (1.98/1.60 m.)

Sail Area 558 sq. ft. (51.83 sq. m.)

Ballast 3,750 lb. (1,705 kg.)

Displacement 7,700 lb.(3,500 kg.)

Ballast/D .49

D/L 220

SA/D 22.9

Mast Height 52′ 2″ (including antennae)

Auxiliary 18-hp. Yanmar saildrive

Designer Sparkman & Stephens

Sailaway Price $289,000

Morris Yachts

(207) 244-5509

www.morrisyachts.com

Friendship 40

LOA 40′ 9″ (12.42 m.)

LWL 30′ 3″ (9.22 m.)

Beam 12′ 10″ (3.91 m.)

Draft (board up/down) 3′ 11″/9′ 2″ (1.19/2.79 m.)

Sail Area 920 sq. ft. (85.46 sq. m.)

Ballast 9,500 lb. (4,319 kg.)

Displacement 22,500 lb. (10,227 kg.)

Ballast/D .42

D/L 363

SA/D 18.5

Mast Height 61′ 0″ (18.59 m.)

Auxiliary 40-hp. Yanmar

Designer Ted Fontaine

Sailaway Price $804,000

Friendship Yacht Company LLC

(401) 682-9102

www.fontainedesigngroup.com