Tornado Seacoast

With barely enough breeze to fill the sails on Symbiosis, our Tayana 37, we ghosted south through the Caicos Passage, heading toward the Dominican Republic. A wall of cumulus clouds stretched to the east beside us, looking only slightly menacing. Suddenly, a dark funnel descended from the sky several miles ahead. My pulse quickened. I put my wife, Noi, on the helm and went forward to douse the main.

The next several minutes were spent in full-throttle maneuvers aimed at skirting the waterspout, which had thickened somewhat and taken on a more ominous vortex shape. Ultimately, our efforts proved unnecessary, and the funnel disappeared into the squall line as quickly as it had formed.

At the time, what we experienced seemed like a freak occurrence. Later, as I did more research, I discovered that tornadoes at sea are not at all unusual and are actually quite common in tropical waters. In fact, we were to encounter two more of them weeks later, off the south coast of St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Even so, I had no idea of which conditions are conducive to waterspout formation, how dangerous they are, how long they typically last, or, most importantly, how to avoid them when sailing. None of the fellow cruisers I spoke with could help either. So I decided to call a few experts to get their thoughts on the subject.

Joseph Golden is a retired National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration meteorologist who is said to know more about waterspouts than anyone else in the world. Beginning in 1967, he helped document hundreds of waterspouts in the Florida Keys over roughly a decade-long period, even taking measurements inside them from the cockpit of a ruggedized World War II training vessel.

While incidents of damage and loss of life at sea from waterspouts are rare, there are occasional documented examples. Golden says that waterspouts can be found virtually all over the world. Their “capital” is Key West, where 100 to 500 of them form each year from about mid-May to late September within a 35-nautical-mile radius of the city. Other waterspout hot spots include the Bahamas and the Caribbean.

Most are “fair-weather” waterspouts, tending to be relatively small. These are usually short-lived, lasting no more than about 12 minutes from formation to demise. By contrast, tornadic waterspouts are larger and can live up to 30 minutes, Golden says.

The typical waterspout is between 10 and 20 meters in diameter, but the largest of them can be 100 meters across. “Those big ones are almost invariably going to be the most dangerous,” he says.

Their destructive power is measured with the same yardstick used for land-based tornadoes: the Enhanced Fujita, or EF, scale. Waterspouts are often weaker than their land-based cousins, ranging from EF0 to occasionally as high as EF2. That’s still plenty dangerous, Golden notes. At the top end, wind speeds can reach more than 175 knots.

For fair-weather waterspouts to form, all you need is sufficiently cool air over warm water. Tornadic waterspouts thrive on warm, humid conditions that would normally produce thunderstorms, explains Wade Szilagyi, director of the Toronto-based International Centre for Waterspout Research.

“Larger weather systems do not necessarily have to be present,” Szilagyi says. “However, cold fronts and squall lines are favorable for waterspout development.”

Golden says large waterspouts usually occur in a slightly disturbed environment. “For example,” he says, “there may be a weak tropical wave that’s affecting the Keys. The largest waterspouts that I have documented occurred in those conditions.”

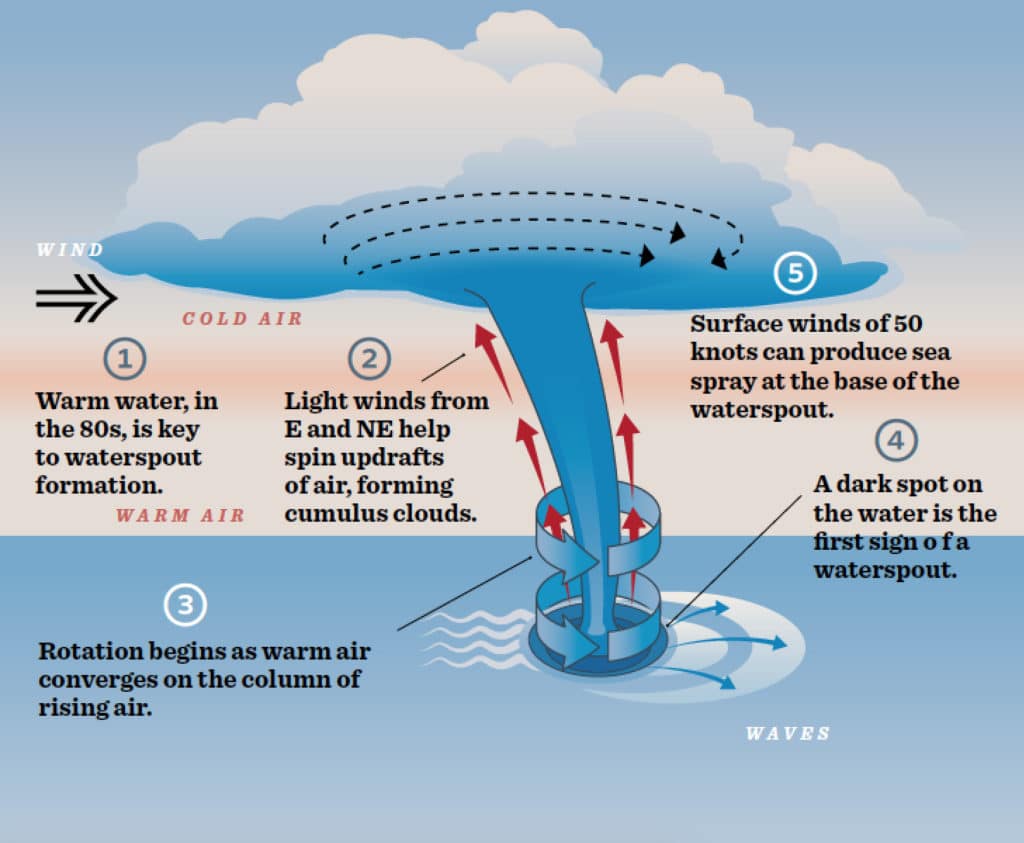

Waterspouts develop most often from about noon until late afternoon or early evening, going through several phases as they do so. They start out as a dark spot on the water, distinguishable from the air but not easily noticed from the deck of a sailboat. The first feature noticeable from sea level is a swirling column of wind-driven surface water known as a “spray ring,” which precedes the distinctive funnel vortex. Winds at the base of the waterspout, even the smallest ones, reach at least 45 knots, Golden says. “Any sailing craft that is caught in even a smaller waterspout is in significant danger,” he adds.

“It isn’t the winds that are going to hurt you; it’s the flying debris from your own boat,” Golden says. “I have seen reports from cargo ships in the channel between Taiwan and mainland China that have been hit broadside and have had large containers thrown around the decks, doing a lot of damage.” What should you do if you encounter a waterspout at sea, as we did aboard Symbiosis?

“Always move at right angles to the apparent direction of a waterspout,” Szilagyi advises.

But determining the direction of travel takes a bit of skill. “If you hold your index finger in front of the funnel and it’s looming larger, sail or motor at 90 degrees, either right or left,” Szilagyi says. “Keep in mind the relation of the spout to any neighboring showers (at the water’s surface). The funnel will tilt away from the showers — that’s the direction it’s moving.”

Waterspouts’ speed of motion — 10 to 15 knots — is slower than land-based tornadoes, but still much faster than most of us can sail or motor. So don’t try to outrun a waterspout along its axis of forward motion.

If you should be so unlucky as to find yourself in imminent contact with a waterspout, you could be dismasted, and any loose objects on deck would become “airborne missiles,” Golden says. He suggests going below deck to avoid flying debris, but notes that there’s a real risk of capsize, especially on a smaller boat.

Lastly, Golden warns against the “foolhardy behavior” he’s witnessed increasingly often on social media.

“Some people in small craft have purposely penetrated waterspouts and managed to come out of it alive. That’s an extremely risky practice,” he says. “If they do it again, they are going to get caught in a big one and could suffer very major damage or even loss of life.”

Scott Neuman is on sabbatical from his job at National Public Radio as he and his wife, Noi, sail the Caribbean aboard Symbiosis, the couple’s Tayana 37. Follow their journey via their blog (svsymbiosis.blogspot.com).