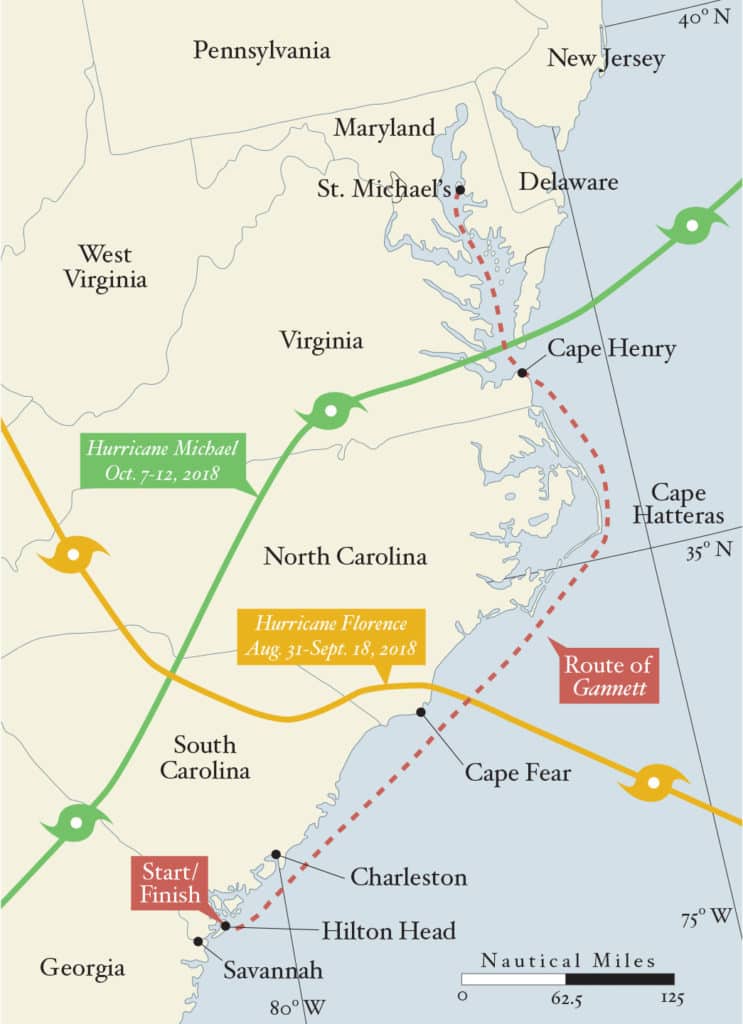

The Chesapeake Maritime Museum in St. Michaels, Maryland, invited me to speak at its annual Mid-Atlantic Small Craft Festival, and I agreed. St. Michaels is 600 nautical miles north of Gannet‘s slip at Skull Creek Marina on South Carolina’s Hilton Head Island. I wanted to sail up. The problem was that my speaking dates were in early October. I would be sailing at the height of the hurricane season.

I prepared Gannet, my Moore 24, in early September, and then I waited. Hurricane Florence was a thousand miles to the southeast heading for the Carolinas. A mandatory evacuation was ordered for the entire South Carolina coast. But was lifted for Hilton Head just before it was due to go into effect.

Hurricane No. 1

Hurricane Florence came ashore early Friday more than 200 miles to the north and brought only moderate wind and rain to Hilton Head. Hoping to ride trailing south winds, I waited until Monday morning and pushed Gannet from its slip into a gray dawn.

The marina is 2 miles from where Skull Creek enters Port Royal Sound. I raised sails and cut the Torqeedo, but our speed dropped below 2 knots, so I turned the electric outboard back on and motor-sailed at 3 knots to the mouth of the creek, where I removed the Torqeedo and outboard bracket from the transom in smooth water. A wise decision because the south wind increased to 20 knots apparent, roughing up the sound as we beat our wet way 8 miles to open water with 3-foot waves breaking over the foredeck.

Finally we were able to turn east-northeast and ease sheets, but with the wind south-southeast, only to a beam reach. Gannet was still taking waves and heeled 30 degrees, and the tiller pilot was working too hard, so I put a reef in the main.

Our route naturally divided into three parts: Hilton Head east-northeast to Cape Hatteras at 350 miles; Hatteras north to Cape Henry at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay at 100 miles; and then Cape Henry to St. Michaels north for another 100 miles. I put in four waypoints all well offshore: off the entrance to the shipping channel into Charleston; the edge of Frying Pan Shoals off North Carolina’s aptly named Cape Fear; the edge of Diamond Shoals off Cape Hatteras; and Cape Henry.

Averaging better than 6 knots, we passed Charleston at 2000 that night. Lights of nine ships were visible to the west of us, and I knew that on this sail I would never enter the monastery of the sea. I am a creature designed to go out across oceans, not along coasts. This time I would seldom have the ocean to myself—land always on one side, ships on the other.

After a night of decreasing wind and a rainy morning, the next afternoon saw us pass a mile west of the platform on the tip of Frying Pan Shoals where the video of the American flag being shredded by Florence was taken. We were in 89 feet of water 29 miles offshore. The contrast couldn’t have been greater than four days earlier. A pleasant, sunny afternoon—10 knots of wind and 2-foot waves. I have been in hurricane-force winds at least eight times but always in deep water far at sea. I cannot imagine the waves such wind must create on shoals.

Another atypical aspect of this sail was that I almost always could receive NOAA weather forecasts on my handheld VHF. Usually I have no access to outside weather information, so I look to the sea, the sky and the barometer, in each seeking signs of change. The NOAA forecasts were of mixed value, sometimes being actionable, sometimes causing unnecessary worry.

The forecast that night, along with the GRIB files I had downloaded with the LuckGrib app Monday morning, was unfortunately accurate. It said the wind would go north on Thursday, heading us, and increase to 20-plus knots.

That and three ships passing to the east caused me to jibe to port at sunset, putting distance between us and the ships, and getting Gannet as far north as possible before the wind shift, which came at 2045 and began an almost sleepless night.

As I jibed the little sloop back to starboard, lightning flickered to the west. Light, fluky wind had me standing in the companionway trimming sails every half-hour or so, until at 2200 I noticed that the sky to the southwest was pitch-black, and I realized the thunderstorms were moving toward us. I barely had time to furl the jib to a scrap before the storms hit with a brief burst of 25- to 30-knot wind, followed by blinding rain, and a half-hour of close lightning strikes and deafening thunder. Back in the great cabin, I listened to big drops of rain splatting on the deck. When the rain eased, the wind went light and fluky once again.

In foul weather gear, I went on deck and unfurled the jib. Because I didn’t know if all the thunderstorms had passed, I left the reef in the main. Spectacular lightning flashed through black sky ahead.

Constant wind shifts kept me awake until 0100 trimming sails, and had me up again for good three hours later. The next morning, the wind finally increased to 10 knots and settled on the beam. I was down below enjoying the settled sailing when I was suddenly startled by a tremendous roar. I leapt to the companionway to find a military jet streaking overhead and two ships to the east. Definitely not the monastery of the sea.

While sitting on deck that afternoon, I noticed a demarcation of water—a clear line between light blue and dark green. As we passed over it, our speed decreased by a knot. We had just left the Gulf Stream.

That night, the wind veered from north-northwest to northeast in a minute, backing the jib and activating the tiller pilot’s off-course alarm. I went on deck and got us sorted out closehauled on a port tack, parallel to the coast, and unfortunately heading out toward the shipping lane. The night—then lovely with silver light on the water from a gibbous moon, Venus and Jupiter in the sky astern—would prove to be another of limited sleep.

The wind quickly increased as predicted, and by 2200, Gannet was pounding into waves. From the companionway, I repeatedly furled the jib deeper and deeper.

Usually I maintain my passage log in my MacBook, but the next day, so much water was coming into the cabin despite the spray hood that I did not dare remove the laptop from its waterproof case. Later I discovered that the middle toggle securing the side of the hood had broken, enabling water to get under it. I recorded our noon position in pencil in a notebook with waterproof paper.

My breakfast was a protein bar. Mixing my usual uncooked oatmeal and trail mix was far too difficult. My dinner was another protein bar. I did manage to have a can of chicken and crackers and dried apricots for lunch.

I tacked from port to starboard at dawn when we were 35 miles east-southeast of Cape Hatteras. It was a day of brutal beauty—wind 20 to 25 knots, gusting 30; dark blue sea; 6-foot white-crested waves slamming into and over Gannet; boat speeds of 7 and 8 knots between waves.

I spent some time on deck, braced with my legs and hanging on with both hands. Ships were often near, and one diverted course for what I felt was a too-close look at my little sloop. Perhaps he wanted to see if I needed help. I didn’t.

On to Chesapeake Bay

I left the reef in the main and the jib deeply furled the next day. Gannet could have carried full sail, but there was no point. We were not going to make Cape Henry before sunset, and I wasn’t going to enter Chesapeake Bay at night. As we ambled along in pleasant sunshine, foul-weather gear, food bags and cushions dried in the cockpit.

Just before sunset, I decided to heave-to 14 miles south of Cape Henry. In light wind, I brought Gannet‘s bow into the wind to come about, and the boom fell off the mast. This happened once before in the Indian Ocean in the middle of the night. The nut comes off the bolt holding the boom to the mast fitting. I had used LocTite on that nut. Still it came off again. With minimal hassle, I managed to get everything back together in the easy conditions. I even still had some daylight in which to work.

I managed to get some sleep until 0130, when then 20 miles south-southeast of Cape Henry with 7 or 8 knots of wind from the southwest, I untied the tiller, jibed and headed in. I had thought I might get back to sleep for an hour, but I didn’t. More than a dozen ships were slowly circling, waiting to enter the bay.

First light Sunday morning found Gannet sailing fast just off Cape Henry and toward a plethora of buoys marking multiple shipping channels, regulation zones and shoals significant to shipping but not Gannet.

The Chesapeake Bay Bridge/Tunnel crosses the 12-mile-wide mouth of the Chesapeake. Most of it is a causeway not far above water level that dips into tunnels at two places to enable ships to pass. I headed for the northern opening. According to the current tables in the AyeTides app, there was a knot of current against us, but we sailed easily through at 5 knots. The second phase of the sail was complete. St. Michaels was now 100 miles north.

NOAA weather gave a Small-Craft Advisory for Monday, with east wind 20 to 25 knots, gusting 30, 5-foot waves and rain, so I worked my way 20 miles northwest to Mobjack Bay on the Virginia side and anchored to wait it out. The wind and rain came and went as predicted.

I woke at 0600 Tuesday to a starry sky and a light east wind. I raised the mainsail and the anchor, unfurled the jib, and by 0620, we were gliding out of Mobjack Bay at 3 knots. I expected to daysail the remaining distance to St. Michaels.

I didn’t. A full moon and my tendency once I start sailing to keep going prevailed. After a sunny, light-wind hatches-open day, sunset found us 2 miles west of Smith Island. A partial rainbow was to the east. Six pelicans in a line glided silently past at boom level, and as Gannet glided north at 4 knots in 5 to 6 knots of wind, I decided to keep going. The wind remained light, and at dawn, there was 30 miles to go.

St. Michaels is on the east side of a peninsula, requiring a 9-mile leg to the northeast before a final twisting 5 miles south. I mounted the Torqeedo on the stern but tilted it out of the water before we made the turn south and started beating into a stiff south wind. The last 2 miles to St. Michaels are complicated by a shoal that can be passed east or west, then a basin of deep water, before a final narrow channel that is in places less than 90 yards wide.

Bright sunlight reflecting on the water made it impossible for me to locate buoys. I had my iPhone with me in the cockpit and followed the course toward them shown on the iSailor chart app, glancing repeatedly at the depth finder, and eventually the buoys appeared as promised. I went west around the shoal in two tacks, but I was too tired to short tack the narrow channel, and lowered the Torqeedo for the last mile and a half.

We had covered 100 miles in 33 hours, 600 miles in nine days, two of them at anchor, with many more sleep-deprived nights than ocean passages thousands of miles longer. I was a tired old man.

The next day I explored the museum and St. Michaels. For anyone with an interest in boats, Chesapeake Bay and how men made their livings from its waters, the Chesapeake Maritime Museum is a fabulous place, with boats and exhibits inside and out, and a lighthouse visitors can enter and climb to the top.

To my eye, one of the prettiest boats is Elf, built in 1888 and said to be the oldest active racing yacht in America. I saw it go out on a Sunday race my first weekend at the museum. St. Michaels is a small, charming town, whose main street is tourist-oriented, and its quiet side streets are lined with beautifully restored and maintained old houses and brick sidewalks.

However, St. Michaels has some odd limitations. There is only one small grocery/liquor store and no place to do laundry. Am I the only sailor ever to arrive with wet, dirty clothes? The nearest laundromat is 10 miles away in Easton. An inexpensive shuttle goes there, but my wife, Carol, was flying in the weekend of the festival and would have a rental car, so I let my clothes fester.

The Mid-Atlantic Small Craft Festival was scheduled for Saturday and Sunday, but boats began to be trailered in a few days earlier. Many of them were beautiful. Mississippi artist Walter Anderson believed that the distinction between artisan and artist is false. I do too. To build a boat in wood is to create a poem.

The festival did the impossible: It turned me into a big-boat owner. Gannet was the longest boat on G Dock. It also had the least freeboard. What? I thought. Don’t these people want to stay dry?

Hurricane No. 2

I gave my talks, which seemed to be well-received. Carol flew home. Gannet and I were ready to sail south. And Hurricane Michael came ashore and headed toward us. I began to wonder if Gannet was a hurricane magnet.

The still-strong remnants of Michael were due to pass the south end of Chesapeake Bay Thursday night. I considered waiting it out at St. Michaels, but I had developed a mild case of a self-diagnosed and -named malady “captiaterraphobia,” a fear of being trapped by land. In St. Michaels I was surrounded by land in all directions and 100 miles from the open ocean. I decided I could find a safe anchorage before Michael arrived, said goodbye, and left Tuesday morning in a flat calm.

I did not get far.

Glassy water and near-calm conditions had me chasing the slightest breath of wind all day. At 1630, dead in the water, I gave up and dropped anchor almost a mile off the shore, having covered all of 9 miles since leaving the dock. There was no shelter where I anchored, but we didn’t need any. It was as smooth as the most perfect harbor.

A light breeze blowing through the open hatches woke me at 0430. We had several miles to go before reaching the main part of Chesapeake Bay. In darkness broken by stars and a few lights on the shore, I raised sails and anchor.

The wind lasted for a mile, then died. Gannet drifted until the breeze returned from the west, and for a change, its bow wave gurgled. At 1500 I anchored 20 miles to the south and 5 miles up the Little Choptank River in 10 to 12 feet of water 200 yards off the north shore. North-northwest winds 35 to 40 knots, gusting higher, were forecast for the following night.

Somehow the area around Savannah, Georgia, and Hilton Head has preempted the name Low Country, but the East Coast is low for a thousand miles. I am not aware of a coastal hill south of New Jersey. The shores of Chesapeake Bay look exactly like Hilton Head. Tall trees. A few scattered homes. Flat.

Thursday was a quiet day at anchor. That afternoon I made my final preparations. I tied a line around the clew of the jib so it could not possibly unfurl. I put shock cords on halyards to prevent them rattling against the mast, and I let out 30 more feet of rode, for a total of 150 feet. While I prefer to anchor on all chain, one of the advantages of mostly line rodes is that line is so easy to bring back in that I do not hesitate to let out more. Gannet‘s rode is 20 feet of ¼-inch chain and 200 feet of ½-inch plaited nylon line, which has a breaking strength of 6,000 pounds, enough to lift the little boat three times. Rain drove me below while I was having a sunset drink on deck. I went to sleep at 2100.

Wind woke me at 0300, gusting 37 knots and pushing Gannet around, but there were no waves, and it remained mostly level. That was the highest wind I saw before I went back to sleep.

Friday the wind continued to blow in the 20s. None of the local boats worked the river. In misty rain, I sailed off the anchor at first light Saturday morning, down the river, and turned south out in the bay. A Small-Craft Advisory was in effect, and it was accurate. But the 20- to 25-knot wind was behind us and provided great sailing. The little sloop flew south.

The mouth of the Potomac River is a surprising 6 miles wide, far wider than the Mississippi River at St. Louis. I was headed for an anchorage just inside the north side of that mouth.

As we neared the river at 1600, I lowered the mainsail, partially furled the jib, and moved the anchor and rode deployment bag onto the foredeck, tying the anchor to the pulpit so it could not fall overboard accidentally. A good move because as we turned into the river, we were stopped dead by 4-foot waves like saw teeth, straight up and down. They broke over the bow and swept the deck. I instantly knew that anchorage was not going to happen and that another all-nighter was, and turned south.

Again I got some sleep sitting at the position I call “central”—sitting in a Sport-a-Seat on the floorboards, facing aft—counting the hours till dawn, but I was continuously awake after 0300 when I had to weave our way through a fleet of anchored ships awaiting dock space.

The wind had decreased, so we slipped almost silently across bows looming high above us and alongside brightly lit hulls. I thought of how different the experience of the sea is of those on board than is mine.

I had timed our arrival at the bridge/tunnel for dawn; at dawn, there it was, 2 miles ahead. I had been sailing under jib alone and now raised the mainsail. Again I headed for the northern break. A ship came out of Norfolk, Virginia, heading east for the southern break.

As the sky brightened, I watched cars and trucks move along the causeway and disappear as they descended into the tunnel. At 0800 Gannet sailed through the gap, and happiness washed over me as waves so often have. I had enjoyed visiting the Chesapeake, my time at the Maritime Museum, the Mid-Atlantic Small Craft Festival and seeing friends again, but those waters are not mine. Although we would turn south and follow the coast back to Skull Creek, there was quiet satisfaction in knowing that the nearest land ahead was 3,000 miles distant.

Webb Chiles recently completed his sixth circumnavigation, this one in his Moore 24 Gannet. Learn more about the intrepid sailor and his travels on his website (inthepresentsea.com).