In the past decade, every time I’ve bought an avocado in the States, I think about a time in 1997, when Windy and I were sailing child-free on the first Del Viento. We were at our first supermarket in Mexico, a subsidized store for the fishing community on Isla Cedros, about halfway down the Baja peninsula. We were there to buy the fixings for guacamole, the dish we’d agreed to bring to a potluck of eight hungry cruisers. I loaded up our basket with enough avocados, tomatoes, green onions, white onions, cilantro, chili peppers, and limes for a guacamole feast. I watched the woman ring up our produce. She paused at the peppers and didn’t bother to ring them up, just tossed them in the bag. I don’t think they were worth a peso. The cost of the avocados turned out to be ten for a dollar’s worth of pesos. Our total bill was less than the peso equivalent of US$2.00. It stands as my benchmark for cheap food.

Until now.

Have you ever been to a place where food is everywhere? Where strangers offer you free food? That happened to Windy a few days ago. She and the girls were walking around Taiohae on Nuku Hiva when a car pulled up beside them. She was busy feeding a skinny dog with snacks from her pack and the girls were scrambling on some rocks that were certainly on someone’s property. The couple in the car appeared stern. They said bonjour without smiling and motioned Windy over to their vehicle. Windy just knew they were going to ask her to get her kids off their property.

“Pamplemousse?” they asked and handed Windy six giant pamplemousse before driving off, each the size to two large grapefruits.

A week prior, on Tahuata, an Australian cruiser stopped by in his dinghy and introduced himself. “You guys want some pamplemousse?” Locals had given him about 30 and he hefted a giant bag of about 15 of them onto our deck.

We don’t pick things on the islands (except for wild basil), but we’ve gathered tons of fresh limes and some oranges and coconuts off the ground.

When we first landed in Vaitahu on Tahuata, a guy called out to us, “Bonjour, pamplemousse?”

“No, merci.”

“Mango?”

We froze in our tracks. He said he would meet us tomorrow morning, on the quay where we landed our dinghy. He said his name was Jimmy.

“Combien ca coute?” I asked.

“Mil franc.”

“Oui, c’est bon. Au revoir.”

I turned to Windy, “That’s kind of steep, almost ten bucks.”

“Depends on what he gives us.”

“Yeah, we’ll see.”

Windy went in the next morning and Jimmy wasn’t there. She went to le magasin to buy some baguettes. They’d sold out.

“How many you need?” a guy called from the back when heard Windy ask the cashier for bread.

“Just a couple.”

“Is that all? Here.” He handed Windy two baguettes.

On the way back to the dinghy, she saw Jimmy. He gave her a bunch of bananas and les pamplemousse. She met his wife.

“You buy only two bread?” she asked.

“All they had,” Windy said.

“Here, two more.” Said Jimmy’s wife, handing Windy more bread.

“Here,” said Jimmy, handing Windy a huge slab of fresh tuna he and some friends were busy filleting in front of her. Then he said something to his wife in Marquesan.

“Our kids are home from school at noon, meet us here then and we’ll take you to pick more fruit.” Jimmy’s wife said.

“Merci, merci beaucoup.” Windy said.

It started raining hard at 11:45. The four of us battened down Del Viento and dutifully climbed into the dinghy, we had an appointment. We arrived dripping wet at Jimmy’s house. They picked out dry clothes for each one of us.

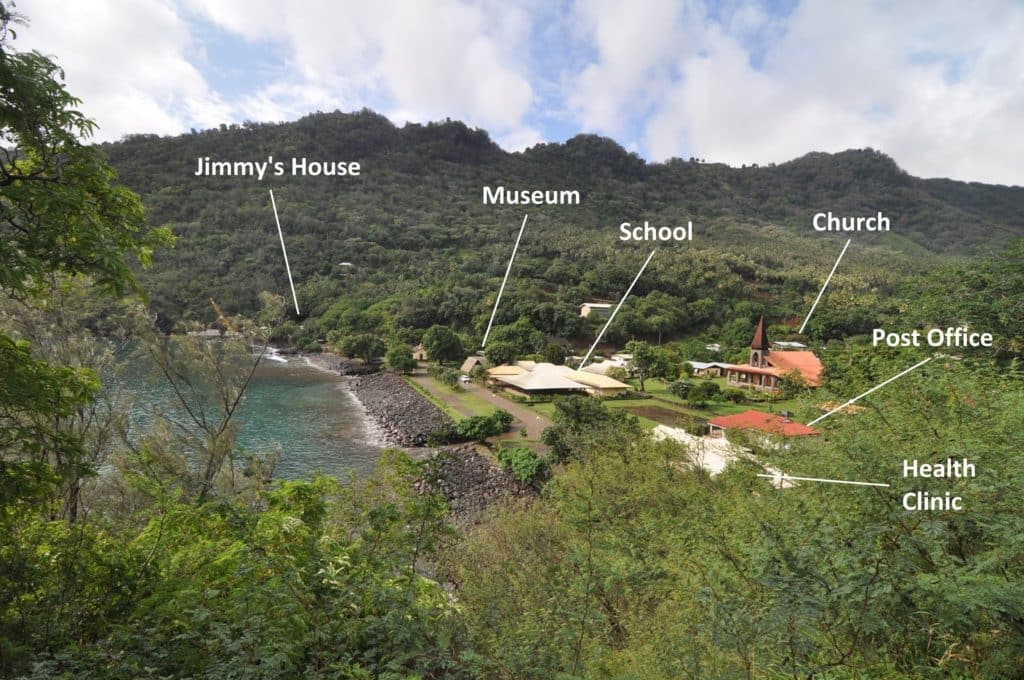

“Oh, no, no, merci, merci,” we each said in turn. Windy passed out some gifts for the kids: a puzzle, a pair of shorts, a stuffed animal. Then Jimmy grabbed a bucket and we all started walking, two families of four. We walked through town, over a hill, and into an adjacent valley. Jimmy’s wife spoke the most English and she showed us plants along the way, told us who lived where, and how she and Jimmy met (I imagined a dance on Nuku Hiva, organized just to mix teens from the different Marquesan islands).

When we got to the valley, Jimmy climbed trees to shake limbs to shed fruit for us, strange fruit we’d never seen, similar to lychee, but sweet like guava. Then he set about husking and preparing coconuts for us; squeezing fresh limes over the top of each one. He picked more limes and mandarin oranges and slowly the bucket began to fill. He eagerly had us try each thing. He wanted us to like everything. He wanted us to see and appreciate his island, how much food there was for the taking, how great their life here was. This was paradise, as he said several times. Why would anyone live anyplace else?

Before I even thought to put a plug in for the diversity and other attributes of the United States, Jimmy’s wife happened to bring up a trip they’d made. They’d been to the States. They were there once, for a conference of some kind. They didn’t care for the United States and do not wish to return.

“Where were you?”

“Nevada, Las Vegas.” She wrinkled her nose like she’d just smelled something awful. But then she added how much they loved Canada—they’d been to Vancouver and found it beautiful.

On the way back to their house, they stopped and asked a relative permission to pick from his garden. Into our bucket went five of the most beautiful eggplants I’ve ever seen and some foot-long green beans. Jimmy’s wife picked flowers for Windy, the girls, and herself to wear. I found a small airline-sized jar of French preserves in my camera case and gave it to them. When we got to their house, Jimmy’s wife ran up and grabbed a bunch of red bananas to put on top of the overflowing bucket. They helped transfer everything from the bucket into bags we’d brought. They told us the name of their oldest daughter—away at school on Nuku Hiva—so we could say hello if we saw her there. They stood on the quay and waved us off for a long time. We smiled and waved back.

In our twenties, we traded our boat for a house and our freedom for careers. In our thirties, we lived the American dream. In our forties, we woke and traded our house for a boat and our careers for freedom. And here we are. Follow along with the Roberston’s onboard Del Viento on their blog at www.logofdelviento.blogspot.com.