J/40 Reborn: A Legendary Cruiser Reinvented for a New Generation

Like father, like son. Al Johnstone’s modern J/40 follows in the award-winning wake of the original—and wins big in 2025.

Like father, like son. Al Johnstone’s modern J/40 follows in the award-winning wake of the original—and wins big in 2025.

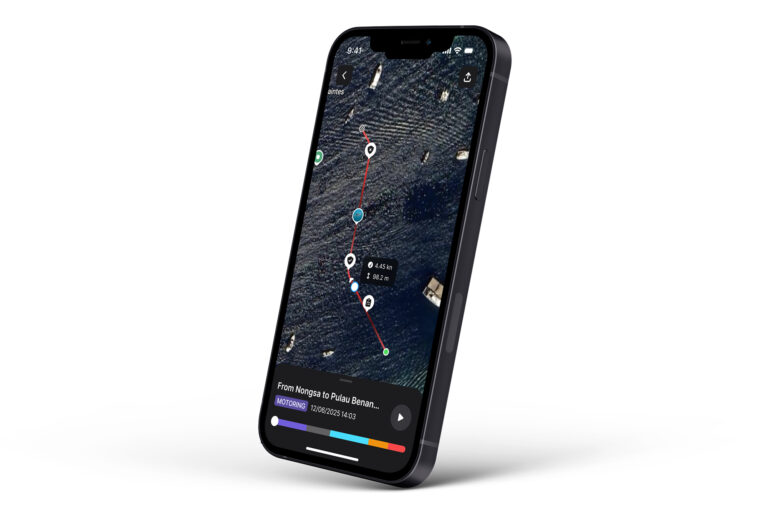

Digital replica of Sailing Uma’s well-known cruising boat becomes first passagemaking yacht in MarineVerse Sailing Club’s virtual platform.

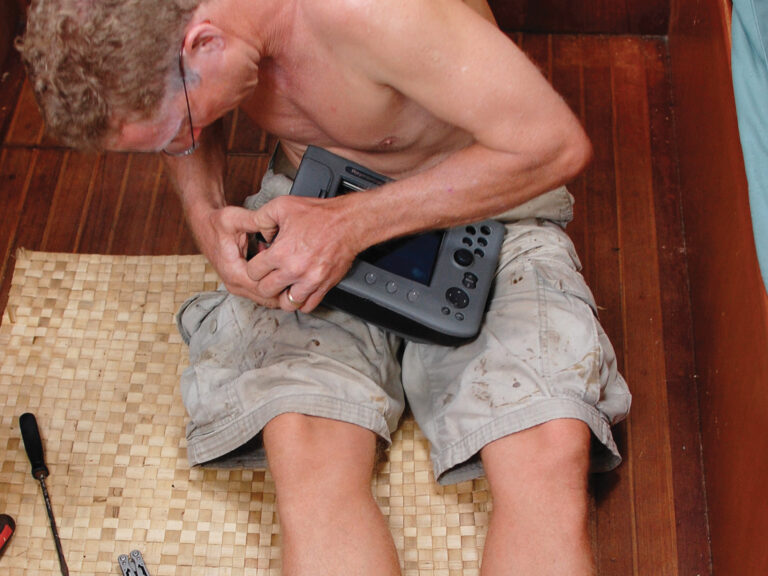

A solenoid valve, latching relay, and new plumbing protect this liveaboard cruiser from dangerous freshwater leaks.

New tiller-mountable, waterproof remote offers flexible, secure throttle control—on board or in hand—for the RemigoOne electric outboard.

Top boatbuilders from around the globe are set to compete for the prestigious Boat of the Year award at the Annapolis Sailboat Show.