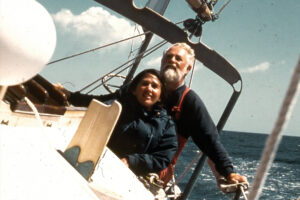

In seven years of full-time sailing, my wife, Alisa, and I have dragged anchor exactly once. I can’t believe I wrote that; now I’ve jinxed us, and we’ll be dragging hither and yon in every anchorage we visit.

But it’s true: only once, and that time barely counts. We were in a very shallow anchorage outside Townsville, Australia, and I had out a ridiculously short amount of scope in a misguided attempt to keep our Crealock 37, Pelagic, swinging inside a pocket of deeper water. Once the chop built up, our anchor was jerked out of the mud bottom and we started sliding downwind.

When you’re just starting out chasing the salty dream, there are few things more potentially confounding than dealing with all the varieties of anchoring situations that you’ll come across. With that in mind, here’s what has worked for us on Pelagic and our current 45-foot cutter, Galactic, in the hopes you might find something useful.

Really, it all comes down to having a reasonable selection of properly sized gear and the basic skills to use it to your advantage. Once you’ve got those things, you can anchor anywhere you go.

Bigger Is Better

Big anchors make for serene sailors. All else being equal, the weight of your anchor will determine how well it sets, and the surface area of the flukes will establish how well it holds. When we bought Galactic, we upgraded her 66-pound Bruce-type anchor to an 88-pound Rocna, one size up from the manufacturer’s already conservative recommendation. Our neighbors in the marina where we were preparing the boat to cross the Pacific shook their heads, which was a good sign — a properly sized anchor looks ridiculous in a marina.

We selected the anchor with dreams of sailing to Patagonia in mind. That 88-pound anchor, after all, is what we count on to hold our 40,000-pound boat in place. On our 16,000-pound Pelagic, it was a 44-pound Spade that did the job.

Don’t think in terms of an anchor size for “reasonable” conditions; prepare for situations where you’ve got only enough room for 3-to-1 scope and a 120-degree wind shift is forecast. On days like those, we go for a hike, confident that Galactic will stay put.(OK, now I’ve really jinxed us.)

As for the particular model of anchor, I’m fairly neutral. On one hand, the Spade and Rocna that we’ve employed have been absolutely trustworthy. After years of using the two designs, I believe the claims their manufacturers make. On the other hand, the owners of our sister ship, Silver Lining, bought a secondhand 75-pound CQR for a fraction of our Rocna’s retail price. With the added weight of 10 feet of half-inch chain fitted between their bow roller and their set-back windlass, they happily anchored in a hundred different spots between California, New Zealand and Alaska.

Lightness Matters Too

While you want a beast of a primary anchor, it’s lightness that matters for another category of anchor: the kedge. This is the anchor you row out in a hurry when something’s gone wrong, and your go-to ground tackle when a stern anchor is required.

In our first year and a half of full-time sailing, in all the places we visited between Alaska and Australia, we went aground exactly zero times. And then, on the Clarence River in New South Wales, we went aground twice in a single day. The first time was no laughing matter; I put Pelagic on a sandbank with a rapidly falling tide. Because our kedge was ready to go in an instant, I was able to row it out and winch us off before we were high and dry.

The standard kedge is a Danforth-type anchor because it’s easy to stow on the stern, and on both our boats we’ve used the aluminum Fortress. I’m a big fan of aluminum for this application because of how easy it is to handle in the dinghy. This consideration is less important with the smaller anchors that smaller boats require. (Size a kedge by the manufacturer’s recommendation for a primary anchor for your boat’s size.) Whatever model you carry, there’s a huge benefit to stowing it attached to the rode and ready to go. We routinely buoy the Fortress when we use it as a stern anchor, so I can retrieve it from the dinghy.

Rode and Redundancy

All-chain rode is the overwhelming choice for long-distance sailors, though a chain-rope combination might be better if you need to be weight-conscious. We carry 315 feet of chain, which allows us to put about 300 feet in the water — enough, in other words, to anchor deep with plenty of scope. And the quality matters too; Galactic came with ⅜-inch proof coil chain, which we upgraded to ⅜-inch G40 for twice the safe working load at about the same weight. If you do go for high-test chain, remember that the increased strength is wasted if you don’t use high-strength shackles. And, as always, it’s possible to save a buck and get sailing sooner rather than just dreaming of your escape; for example, on Pelagic we used ⅜-inch BBB, a cheaper choice than G40 that worked fine.

Once you’ve got the chain, you’ve got to mark it with spray paint or zip ties so you know how much you’re putting out (duh). But how much are you supposed to put out, anyway? When we became friends with Colin Price, the (quite) English captain and father on the family catamaran Pacific Bliss, he had one burning question about American sailors: Why did they put out so much bloody scope?

I explained that there were seamanship books in America that everyone purchased when they were starting out, and they recommended 7-to-1 scope. So that’s what Americans do.

Colin was scandalized. “Seven to one?” he asked. “Are you quite sure?”

And yes, Colin is right, as tremendous scope is often no longer necessary — 7-to-1 worked in the old days, when anchor designs were less advanced and there was tons of room in every anchorage. We usually do 4-to-1, just because we’re conservative about such matters, but 3-to-1 is fine if the anchorage is crowded or the water is deep. After all, we’ve got a good anchor.

But if it really starts to blow, putting out more scope — all the way to 8-to-1 or even 10-to-1 — is your first and best defense.

Redundancy is also important. Your primary and kedge anchors will see you through more than 99 percent of anchoring situations, but it’s the rare long-distance sailor who carries only two hooks. If you ever run into really severe weather, or if you lose your primary far from any chance of resupply, you have to have more metal on hand to put in the water. On Galactic we have that Bruce copy as a backup, as well as 40 feet of the old proof coil chain and lots of heavy nylon rode with spliced-on thimbles, in case we ever lose our primary anchor and chain. We also carry a 75-pound folding monster as an extra extra. With all that gear and a handful of spare shackles, we can rig up any number of backup systems.

Snub It, Set It

A windlass is designed only to pull up the anchor, not to take the load of an anchored boat. And if conditions get really bad, you can’t have waves rocking your boat back against a bar-tight chain. In that case, something has to give; you’ll either pull deck gear off your boat, or the anchor out of the bottom.

The solution is a snubber, a length of nylon on a chain hook, which takes the load to a cleat and stretches to prevent shock-loading to the gear. On Galactic, we use a 30-foot piece of ⅝-inch nylon, and if conditions ever get much worse for us than they have in the past, we have a second chain hook and longer, stretchier bits of nylon line that we could use to make an extra elastic snubber.

Now, if you just chuck the pick over the side and crack a cold one, how do you know you’ll hold when a squall comes through in the middle of the night? The answer is that you set the anchor — hard. I power up to 2,000 rpm (just about cruising revs for us) in reverse every time we set the anchor. I’m buying peace of mind; if the anchor can hold that load, it can hold in any weather that’s likely to come along. And if we have doubts about the bottom, I back down on it extra slowly. It’s not uncommon for me to spend 10 minutes slowly increasing the rpm, making quick transits from objects onshore to see if we’re moving, and occasionally going up to the bow to see if the chain is giving a steady pull or if it’s jumping around.

Tricky Business

That gear and those skills will allow you to handle the routine situations. But what about more challenging moments? There are a few extra tricks that you can break out if need be. For example, if we’re trying to sit on a little patch of sand that’s surrounded by coral, we use two anchors in series: the Fortress attached to the head of the Rocna with 12 feet of chain. The Rocna doesn’t actually set, but instead acts as a massive kellet (or weight) on the rode for the Fortress. This setup lets us sit happily on 2-to-1 scope, though we use it only if we’re confident that the wind direction won’t change, as we wouldn’t trust the Fortress to reset itself.

Another great trick when anchoring near coral is to float your chain with fenders or buoys so it doesn’t foul the bottom. We usually leave the half of the rode closest to the anchor unbuoyed, and then tie buoys to the second half of the chain so it floats free of obstructions on the bottom. When the wind comes up strong, the load on the rode pulls the chain down to its normal depth, preserving the desired angle of pull on the anchor.So, in a nutshell, that’s what we’ve learned about anchoring in seven years of cruising. The real knowledge, though — the feel and art of the thing — comes only with experience. So get out there beyond the horizon, and find yourself a palm-fringed bay to drop the hook in.

Mike Litzow is the author of South from Alaska: Sailing to Australia with a Baby for Crew. If you have further questions about anchoring, get in touch at his blog, www.thelifegalactic.blogspot.com. At press time, Mike and his family were in Puerto Williams, Chile, aboard Galactic.