Oleksiy Vorobyov, one of eight riggers on the worlds largest sailing vessel, paused on the foredeck of the 439-foot Royal Clipper to consider his predicament. By Caribbean standards, it was a cool day, but the Ukrainian was drenched in sweat as he gripped a grinder in his right hand. Clamped in his left hand was a wooden block the size of a melon. The oak and bronze block, one of some 200 aboard the Royal Clipper, represented a nod to tradition aboard a ship that blends 21st-century technology with a 19th-century sail plan. Oleksiy didnt pretend to comprehend the concept.

A 15-knot trade wind was driving the five-masted, fully rigged ship steadily toward the Grenadines under a robins-egg-blue sky. As the clipper bow plowed through the five-foot swells with barely a hiss, the ships cloud of sails cast a broad shadow over the water ahead–and Oleksiy cogitated. “Im sure we can afford good stainless-steel block,” he said with a thick Russian accent. “But owner wants traditional sailing ship, so we use wooden block.” He flicked an ash from his cigarette, then smiled. “This is never-ending project, but its my job. Better here than Baltic Sea, you think?”

I felt a kinship with Oleksiy. The last time I was in the Grenadines, eight years before, I was rebuilding the wooden mainsheet block on our 32-foot gaff-rigged ketch, Tosca, as we got ready for the hop to Venezuela. Theresa, my girlfriend at the time and now my wife, was recaulking the weathered teak deck, and our third crewmember, Steve Cannon, was treating the bilge with a noxious blend of linseed oil and wood preservative. We were nearly broke, mired in an endless cycle of maintenance chores, and spending more time in hardware stores than on sandy beaches–but we were happy. The trick, we learned, was to keep things in perspective. A better-here-than-the-Baltic-Sea attitude can work wonders when tropical dreams start to founder.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| Darrell Nicholson|

| |

|

|

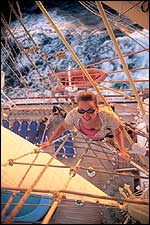

| And this was my quandary aboard the Royal Clipper, a ship that so tilts ones frame of reference that its numbers alone–56,000 square feet of sail area, a 500-horsepower bow thruster, an 18-inch-diameter rudder shaft, a four-ton bow anchor–make your head spin. And to swing in the rope net under the bowsprit, five stories above the foam of the bow wave, would leave most anyone weak in the knees. From the outset of this voyage, Id wanted to stay true to my small-boat roots and not be wooed by bigness or splendor, but my resistance began to fade fast.

Along with 200 passengers and 105 crewmembers, Theresa and I had boarded the ship 11 hours earlier in Barbados for the night sail to Carriacou, in the Grenadines, our first stop on a seven-day loop through the Windward Isles. Shortly after our departure, the 46-foot-long bowsprit began jousting with Orion as the ship gently rolled in the ocean swell and glided westward at 11 knots. Admiring starlight reflected in the varnished teak caprail that’s 10 inches wide and nearly a quarter of a mile long, I tried to imagine the man-hours invested in that finish. By the time the last coat had dried on one end, surely the sanding would begin at the other.

At the bridge I met the first mate, Oleksandr Onishchenko, who led me into the darkened wheelhouse, where three GPS units tracked our course and two radar screens scanned the horizon. After erasing the plots on the British Admiralty chart from the previous week’s cruise, Oleksandr extended a pair of dividers to mark the ship’s 2200 position, then switched off the red-shaded light over the chart table.

His routine was little different from one Id carried out myself hundreds of times, but in this chamber bristling with the latest electronics, the contrast between the LED readouts and Oleksandrs carefully penciled fixes was downright eerie. It was as if the Royal Clipper, a fairly honest replica of the German P-Liner Preussen, which was sunk in a collision in 1910, operated in a strange netherworld, neither past nor present. And with each tick of the log and each stroke of the pencil, her passengers and crew were being slowly drawn into it.

“If this was Russian training ship, wed need three times as many deck crew,” said Oleksandr, who uttered “Russian training ship” as if this were the standard by which any tall ship should be compared. It was an attitude that seemed to prevail among the deck crew of the Royal Clipper, a large percentage of whom had learned their trade aboard the sail-training vessels of the former Soviet republics. But Royal Clipper was no Russian training ship, and in many respects, she was a far cry from the Preussen, which, until her last voyage, made profitable runs around Cape Horn carrying nitrate and bulk cargo between Chile and Europe.

Once at sea, the Royal Clippers deck watch consisted of just three men: one officer and two ordinary seamen. Belowdecks, two computers monitored the electrical system, pumps, and machinery, while the engineer on watch occasionally clicked a mouse. Sailhandling was managed by an ingenious system of more than 100 belaying pins and snubbing drums (around which running rigging was led to larger electric winches, when needed), eight 18-inch-diameter electric winches (to raise halyards and trim sheets), five hydraulic Jarvis windlasses (first tested on the Preussen in 1897, these simultaneously braced all of the yards on each of the masts), and roller furling on the staysail stays and yards (from which the sails dropped like window blinds).

The setup allows 16 crew to command more than an acre of sail without ever having to leave the deck. A traditional rig, in which all sails were either hanked on stays or furled and brailed on yards, would require more manpower than that at each mast. But even with these advantages, coaxing the Royal Clipper through the eye of the wind under sail is no easy feat. The only practical way to do this is to boxhaul, in which the head yards are braced flat aback, the helm is put hard a-lee, and the ship gathers sternway before sails are trimmed for the opposite tack. The maneuver requires every deckhand, including those taking a much needed break on their off watch. When I later mentioned to the rigger Oleksiy that Id sure like to see the Royal Clipper strut her stuff and suggested he could pass this hint on to the captain, he gave me a friendly scowl and said, “Well boxhaul as soon as I finish with these blocks.”

The Lap of Luxury

Aboard Tosca, on an ordinary morning at sea, I’d awaken bleary-eyed for the 0600 watch, pour a cup of last night’s coffee from the Thermos, pull the least-battered banana from the mizzen shroud, and grab a soggy granola bar from the lazarette. My shower was a bucket of salt water, followed by a squirt of fresh water and dampened towel. Daybreak on the Royal Clipper erased any nostalgia I felt for those days.

On our first morning aboard the ship, as the sunrise filtered into our mahogany-veneered stateroom, I peered out our porthole to the sapphire water below, then perused the schedule of activities that our cabin attendant had placed, along with Swiss chocolates, on our pillows the night before. According to the itinerary, wed be spending the day snorkeling near Carriacou. Though the cruise schedule is fixed well in advance, theres wiggle room to accommodate wind shifts or to slip into an alternate anchorage when the weather demands.

I noted the spas special for the day–a warm seaweed wrap–then padded across the carpet and ducked into the hot shower. With the ships two watermakers pumping out 40,000 gallons a day, I could linger as long as I liked. After my ablution, I could take a dip in one of three pools (one with a glass bottom filtering light into the dining room below), work up a sweat in the health spa (with two submarine portholes revealing the depths below our keel), settle down with a good book in the Edwardian library, or hang out in the air-conditioned piano bar. It was all very lovely, but also a little unsettling. Any minute I expected the Archangel Michael to appear and tell me thered been a terrible mistake.

Admittedly, Im probably the least-qualified person to rate such ancillary charms aboard the $75 million dream ship of shipping magnate Michael Krafft. Launched in 2000 to join Star Clippers much smaller twin clippers, the Star Flyer and Star Clipper, the Royal Clipper, I was told, represented the pinnacle of luxury passenger sailing. But I hadnt come to marvel at the bathtubs (tested for size by Krafft himself) in the clipper cabins; Id come to sail. And in my experience, true sailing entailed bruises, rare tropical diseases, and wearing the same T-shirt three days in a row. Unless the Thai masseuse had a mean streak, malarial mosquitoes lingered in the piano bar, or the laundry service mistook my wardrobe for dishrags, this wasnt going to happen on the Royal Clipper.

Theresa, who was four months pregnant, was, of course, delighted by our temporary digs. “Relax and enjoy yourself,” she said, when I pointed out with genuine dismay that wed spent the whole night running in a following sea toward the Grenadines without any need for the leeboards stowed under our full-size bed. “Look, the breakfast buffet is already spread out,” she said.

As I watched her heap her plate with sugar apples, mango, and cinnamon crepes, I realized that even if this wasnt exactly sailing as I knew it, at least Señor Tiny (his nom de womb) would pack some meat on his newly formed limbs as his mom sampled the offerings aboard the Royal Clipper. So I downed my freshly brewed coffee, loaded my plate with pineapple, and began to wonder how Id pass the next few days. It was just about then that the Royal Clipper–5,000 tons of iron, steel, and canvas–assumed a perceptible heel.

It was a mild cant, but more than Id ever expected aboard a ship as big as the Royal Clipper, whose maximum angle of heel is about seven degrees. I ran up on deck and saw that we were booming along at 11 knots. The islands of the Grenadines were strung out before us like emerald stepping-stones on a turquoise lake. The new deck officer, Sergey Utitsyn, was watching with mild amusement as a small flotilla of sloops and catamarans, mere flotsam in our path, jibed and tacked for a closer look.

Nearby stood a Swiss passenger, Sven Müller, 33, who was there with his wife, Andrea, scouting territory for a future bareboat charter. Müller, who races a one-tonner on Switzerlands Bodensee (Lake Constance), figured this trip was an ideal way to narrow down the area they wanted to sail on their own. Our leg north from Carriacou to Martinique, with stops in St. Vincent and Bequia, offered a nice sampling of the region. For most of the trip, I knew just where to find him and Andrea: lying in my favorite spot, the ample net under the bowsprit. “We dont have sailing like this on Lake Constance,” Sven would say each time I joined them.

Conquest of a Cruiser

My conversion began in earnest at sunset on the second night as we prepared to weigh anchor in the lee of Carriacou, just a few hundred yards from where Tosca had once lain nestled for two days. Captain Jürgen Müller, who skippers the 60-foot racer/cruiser Germania VI in his downtime, strolled the bridgedeck with his thumbs hooked in the pockets of his creased, white Bermuda shorts. An old-school ship’s master, he casually aligned the vanes on port and starboard peloruses to take bearings on two nearby islands that flanked the ship. Pacing back and forth a few yards behind the Polish helmsman, Krzysztof Jaroszewski, the captain uttered barely audible commands: “Port rudder 10 degrees. . . . Port 20 degrees, hard to port.”

Then came the music, softly at first, then piping louder over the ship’s speakers: a magnificent, heraldic, triumphant arrangement–ironically from Conquest of Paradise, a decent soundtrack to a terrible 1992 film. (Tom Selleck as King Ferdinand V? What was Hollywood thinking?) The horns chimed in just as the anchor windlass begins to rumble.

“I wonder who gives the order to ‘Cue the music’?” Theresa whispered in my ear.

OK, it was a bit hokey, but as Captain Jürgen strode the bridge, glancing over each rail to watch as the ship slowly came up on its anchor, I couldnt escape the feeling that we were witnessing something remarkable. And we were. Manning two electric winches, one port and one starboard, the deck crew set and backed three of the five foresails. In a moment, the anchor clanged into the hawse pipe. Captain Jürgen took one last look at the port pelorus and turned his nose to the wind before giving the order to tack the jibs.

Moments later, the roller furlers in the yards on the foremast began dropping sails until 30,000 square feet of canvas, just over half of the sail area, ushered us back out to sea. As if they were taking the family daysailer out for a spin, the captain and his crew had sailed off the hook, spun the 5,000-ton ship in a fairly tight spot, and got under way using only the power of the wind. As if on cue, the sun dipped below the horizon and delivered a conspicuous green flash. Captain Jürgen turned and winked at the passengers clustered near the bridge. “Did you see that?” he said with a grin.

The engineer, Louis Deravet, a Belgian who wore a perpetual grin on his face, stood beside the captain, beaming more brightly than usual. Once clear of land, more sails unfurled until we were cracking along at nine-point-five knots. The sky shifted from yellow to purple as the few lights on the hills of Carriacou winked good-bye. Neptune, forgive me: I was having fun.

That night, we reached southward under reduced sail toward Grenada. The moist trade breeze had eased, but to prevent the boat from overshooting her mark, the deck crew reduced sail to only about 20,000 square feet, enough to keep us loping along at five knots. I ducked below to don a windbreaker, and when I returned to the deck, I flopped in a chaise longue and inhaled the sweet fragrance of the islands.

We covered the evening passage in just a few hours, but since we couldnt enter St. Georges until morning, we eased the yards, reduced sail, and bore off to the southwest. I watched the shore until the last lights of St. Georges twinkled off in the distance, then showered again before dinner. Having indulged in two showers in one day, my fall from grace was complete. Id never be taken seriously as a cruiser again. Frankly, I didnt care.

The next day Captain Jürgen invited passengers to the conference room to regale them with sea stories and explain the subtle art of sailing a five-masted ship. “I believe that we can only build a ship so big and still call it a sailing ship,” said Captain Jürgen. “And we are right at the threshold with this boat. They used to say that the captain didnt sail the Preussen, the Preussen sailed the captain. Happily for me, this is not the case with the Royal Clipper. I myself am surprised at how well she handles.”

His only complaint was the slightly unbalanced sail plan, which gave the Royal Clipper about eight degrees of weather helm under full sail. So except when racing, maneuvering, or posing for photos, the ship rarely flew the spanker or the topsails on the jigger mast, which, he said, had little effect on the boats speed. “Under engine power, we require about 4,000 horsepower to go about 12 knots; under trade-wind conditions, we can sail at about 14 knots. In Force 9 winds in the Mediterranean”–shortly after the boats launch–“we hit 17 knots with only two jibs flying. Here in the Caribbean, as you can see, we have to reduce sail so we dont go too far from where we want to be in the morning. These are perfect sailing conditions for this ship, and that, of course, is why we are here.”

This was just what Id hoped hed say.

That evening in St. Georges, a steel band came aboard, and I was glad to find the Grenadians hadnt lost their sense of humor during the eight years Id been away. As the passengers shimmied to the tinkling drums, the prelude to a familiar melody rang out: the theme song to Titanic. I glimpsed a sly smile on the bandleaders face as he silently mouthed the songs words.

The rest of the week flew by in a blur of night sails and day trips on St. Vincent, Bequia, and Martinique, and though I could have easily stayed aboard for another month, I was looking forward to the last day of our cruise, a 120-mile windward bash from Martinique back to Barbados. Unless Captain Jürgen had found a previously unknown countercurrent, I reckoned it was impossible to make the passage under sail alone. For two centuries, Barbados best defense was its location, some 100 miles to windward of the nearest Caribbean isle. As it turned out, I was right. A sail to Barbados on the Royal Clipper, which can point about 80 degrees to the wind, wasnt possible, at least not in time to pick up the passengers for the next weeks cruise.

So on the afternoon of the last day, we ripped out of Fort de France in 18 knots of gusty wind, the strongest breeze of our trip, and Captain Jürgen kept the square sails up as long as he could, fending off a challenge from a 50-foot catamaran. As we rounded Diamond Rock and turned hard on the wind, the square sails were furled, leaving the steadying lower staysails and twin 2,500-horsepower Caterpillars to carry us home.

As our last sunset aboard the Royal Clipper was lighting up the hills of Martinique, Theresa and I strolled to the foredeck and climbed into the net beneath the bowsprit. Lying there on our backs, we watched the last rays paint the sails golden and listened to the rush of the sea. What an extraordinary ride.

“So, what do you think of Captain Jürgen for a name?” I asked Theresa, glancing at her waist. She looked at me like Id gone mad. “OK, how about Oleksiy?”

She smiled, took my hand, and placed it on her belly: “Does this feel like an Oleksiy to you?”

By the time the Royal Clipper met the first swells of the Atlantic, the worlds biggest sailing ship seemed a pretty small thing. But at that particular moment, it was a fine place to be.

Darrell Nicholson is Cruising Worlds senior editor. Darrell and Theresas son, Ben, was born on August 13, 2002.