Back in the old days, from the earliest times of ocean racing to the late 1970s, cruising boats often raced and ocean racers often cruised. The best dual-purpose racer/cruisers, in my opinion, were designed and built between the early 1950s and the late 1970s. During that period, nearly all hatches were double-opening designs that enabled them to open facing forward in port, gathering plenty of air. At sea, they opened facing aft, still gathering loads of fresh air.

When the spray started flying, dodgers were rigged over the hatches to prevent water from being driven under them. The dodgers were secured to a grooved wooden breakwater that extended across the forward side of the hatch and down both sides by any one of three attachments. Alternatively, you could use an aluminium extrusion that accepted a luff rope sewn to the dodger. With the arrival of mass-produced boats, the double-opening hatch almost disappeared. The vast majority of cruising boats now have only single-opening hatches and no dodgers over them. In hot climates, if it starts raining in port, the hatches must be closed, and the boat becomes a sweatbox. At sea it becomes a sauna, as the hatches must be shut to keep spray from getting below. Modern, low-profile dorade ventilators, which we’ll discuss momentarily, do not gather enough air and thus worsen this condition.

The good news is that it’s still possible to retrofit double-opening hatches in the modern fiberglass boat. In Taiwan, H.B.I. Marine (hbimarine.com) still builds double-opening hatches with stainless-steel frames. They come in two sizes (24-by-24 inches or 34-by-34 inches) and can be delivered to the States in about five weeks.

The one drawback to double-opening hatches occurs when you’re in port with the hatches open and it starts to rain. Someone has to go topsides, get wet, close the hatch, switch the pins, and reopen it facing aft. This eliminates most of the rain but still allows some air down below.

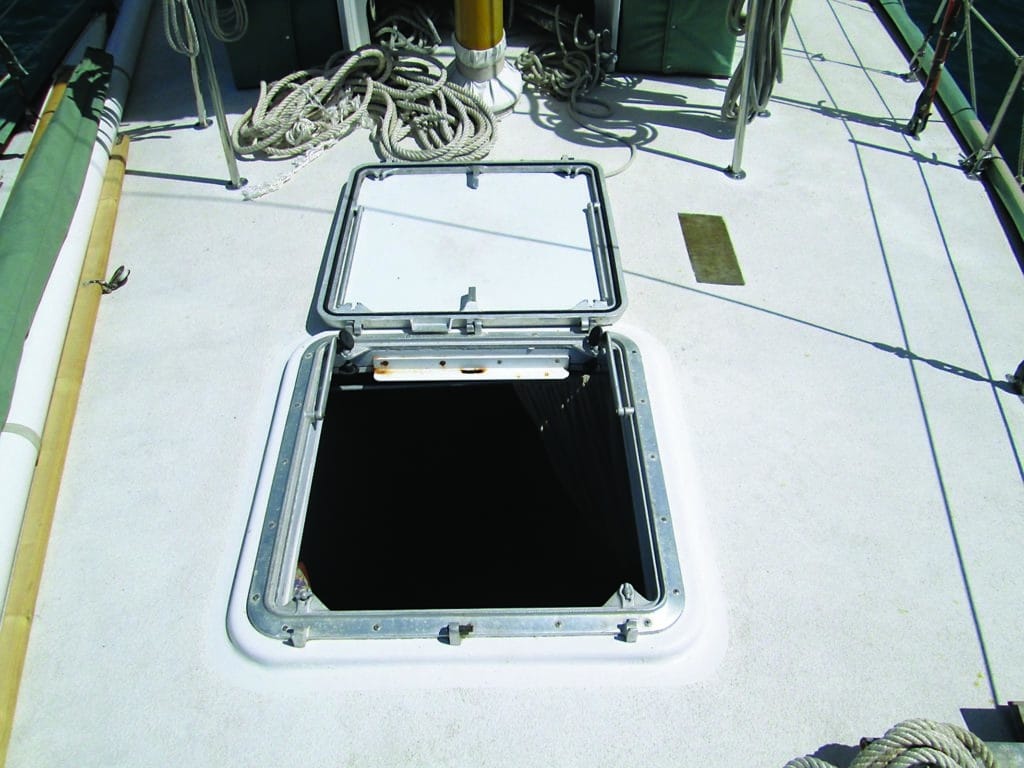

Recently, while walking down a marina dock in St. Lucia’s Rodney Bay, I saw a different double-opening hatch that could be reversed without going on deck, on a Bill Tripp-designed Mercer 44 called Synia, built by Cape Cod Shipbuilding in 1978. Not only could the hatch be reversed from below, but as the accompanying photos show, it could fully open fore or aft and lie flat on the deck.

Chuck Hogan has owned Synia for 10 years, and with his wife has cruised extensively down the east coast of Florida and through the Caribbean. He is very enthusiastic about the hatch, of which both the deck frames and hatch frames are cast aluminum. He reports that when the hatch is closed and properly secured at all four corners, it never leaks a drop. It’s also stood the test of time, as the previous owner logged over 52,000 nautical miles aboard the boat with that original hatch, including extensive high-latitude sailing.

Chuck did some investigating and discovered the hatch was made by Bomar in the 1970s and used aboard boats built by Cape Cod Shipbuilding, but not widely marketed elsewhere. (The French company Goiot also made double-opening hatches at one time, but no longer offers them.) Happily, Bomar still offers the double-opening option in a few of its original Cast 100 series models; depending on size, they range in price from $1,400 to $3,600. Bomar also offers the double-opening option in its line of Hood Yacht Systems stainless-steel deck hatches. For more information, contact the company (bomar@pompanette.com).

My advice is to spend some money, install double-opening hatches, and ensure your boat is well-ventilated both at sea and in port.

Dutiful Dorade Vents

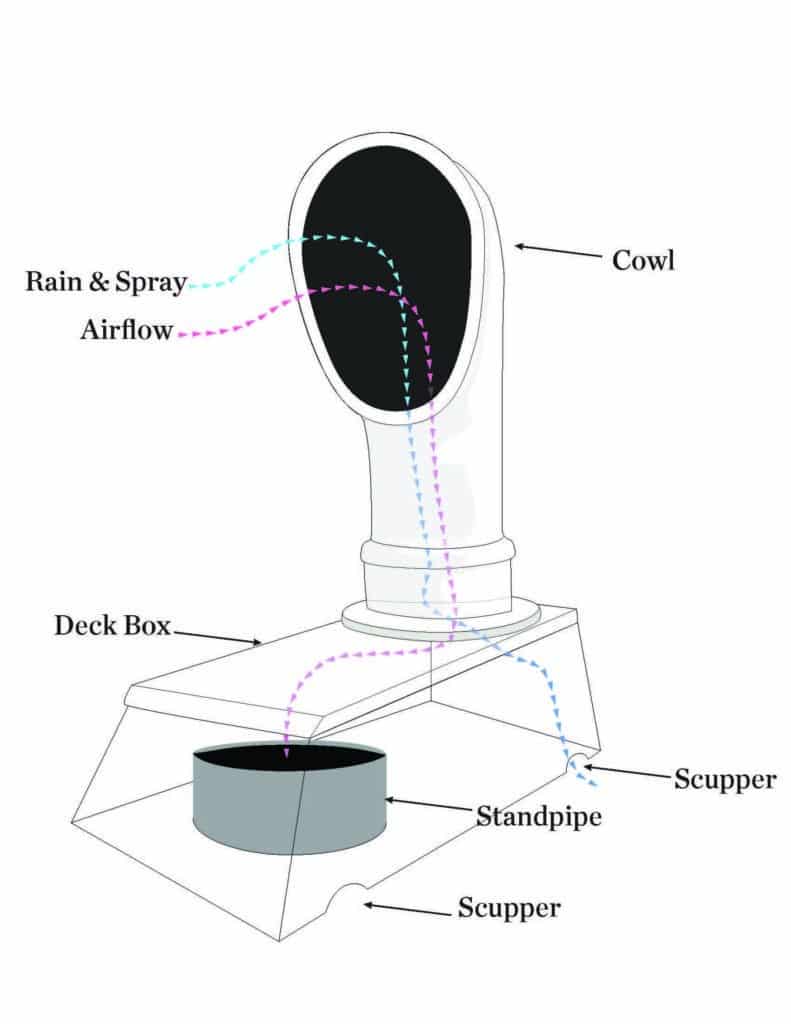

The original dorade ventilators were named after the famous yacht of the same name, designed by Olin Stephens in 1929. Dorade and other yachts of her era had extremely low freeboard, and dorade vents provided air down below when the spray was flying, the decks were awash, and the hatches were dogged down. The boat has undergone several refits and is still going strong; the accompanying photo on the previous page shows her dorade vent, which stands a full 3 feet above the deck. Because it’s tall, the vent’s box only has to absorb and remove rain and spray, which isn’t a problem given the box’s large drain holes.

In contrast, on modern yachts the so-called dorades are so low and close to the deck that they gather in little air. In heavy weather, these low ventilators take in a lot of water. The drain holes in contemporary dorade boxes are often too small and misplaced, making them little more than heavy-weather scoops that funnel water belowdecks.

In my opinion, the best stock dorade ventilators come from P.E. Luke (peluke.com) in Boothbay, Maine, available in either aluminum or bronze and in several sizes. Mounted on a high, proper box, these vents are tall enough to gather plenty of air but not much water — only spray. Furthermore, the lip on the Luke ventilator is so small that there is no danger of a flogging sheet inadvertently throwing a half-hitch around it and tearing it out.

All too often dorade boxes are installed in the side of the cabin house with the drain holes facing outboard. This is fine in port, but at sea, if you’re sailing in heavy weather on the same tack for a fairly long time, the windward dorade box will gradually fill with water. If the water level in the box becomes higher than its internal standpipe, it will flow down below instead of over the side. To see if your dorades are susceptible, put them to the bucket test. Go for a sail and strap the boat down hard on the wind. At intervals of about 20 seconds, throw four buckets of water at the windward dorade. I’ll bet you a few beers — Heinekens, of course — that the box will flood and water will seep belowdecks.

To cure this problem, plug up the outboard drain holes and cut two new ones in the aft end of the dorade box. Make sure they are big enough to stick your thumb inside. If your boat does not have dorade ventilators, I recommend buying a set from Luke and fabricating boxes of fiberglass or wood. These should be a minimum of 4 inches high (6 is better) and 14 inches long. For the top of the box, use Lexan, Lucite or plexiglass to shine light down below.

At 85 and still typing away, Don Street — legendary sailor, cruising guide author and consumer of green-bottled malt beverages from Holland — is the dean of American sailing writers.