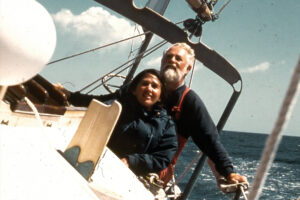

It’s not often that you get buzzed by a Coast Guard helicopter wondering what you could possibly be doing so far from civilization. But then, it’s rare to be sailing a wooden cutter toward the U.S.-Russia border in the Bering Sea in the first place. My husband, Seth, and I were a few miles away from the border — an imaginary but important line across the heaving, gray seas — on a cold, overcast day in July when the helicopter appeared. Our American voices blithely responding over the VHF that we were bound to Nome, Alaska, and thence to Barrow, to see the northernmost point of our country, satisfied them, although I wouldn’t be surprised if they were privately still mystified. A little wooden sailboat? Heading for the churning seas of the Bering Strait and the hard plates of ice covering most of the Alaskan Arctic? Crazy. Maybe, but then again, maybe not. Seth and I had done the “30-year refit” that was due on our cold-molded cutter, Celeste, at Platypus Marine in Washington state a year and a half earlier. It had included a Kevlar belt at the waterline to protect against ice, a new diesel engine, new satellite communications from OCENS, new electronics, a revamped electrical system that included new Rolls AGM batteries, and all kinds of safety equipment down to a Katadyn Survivor manual desalinator in our ditch bag.

Even if we were prepared — and experienced, with almost 40,000 miles under our life vests — we might still be crazy, because why would anyone sail up there? Why risk the ice? Why endure the cold and the nauseating waves? Our answer was simply that we wanted to see the Arctic Ocean from the deck of our own little boat. That’s akin to Everest explorer George Mallory’s “Because it’s there” and mountaineer Sir Edmund Hillary’s “You really climb for the hell of it” — not a very satisfactory reply for those who don’t share the same desire, but the truth.

In 2014, we had made — to our minds — a breathtaking voyage northwest from Washington state to the Aleutian Islands (see Cruising the Alaskan Peninsula). We’d observed black bears and sea otters on western Vancouver Island, sailed past waterfalls dropping hundreds of feet to the sea, gawked at the snowcapped peaks of southeast Alaska and picked our way among icebergs calving off glaciers in Prince William Sound. We’d marveled at humpback whales bubble-net feeding and brown bears fishing for salmon. At the end, we’d reached the misty islands of the Aleutians, a forgotten outpost of America that lies farther west than Hawaii.

Instead of retracing our steps in 2015, however, we swung the bow north out of Dutch Harbor. As we hoisted sail, the mountains and glaciers of the Aleutians behind us glowed in the sunset. Ahead lay the Bering Sea, Bering Strait and the Arctic Circle. Two days passed among lumpy seas, 20-knot southeast winds and hundreds of seabirds: murres, fulmars, storm petrels, even a Laysan albatross. We even saw a humpback whale spy-hopping, just before we reached the Pribilof Islands.

Originally uninhabited, the Pribilofs served as a kind of penal colony for Russians and enslaved Aleut natives, who turned the fur seal population into coats and hats, but are now — more happily — known for their nesting seabirds. Being amateur bird nerds and obsessive wildlife enthusiasts, Seth and I spent several days — in rain, fog and sun — lying above the cliffs, training binoculars on red-faced cormorants, crested auklets, tufted puffins and red-legged kittiwakes. We crouched in blinds to watch bull fur seals bark at each other over their harems, and we hid behind rocks to photograph the blue morph arctic foxes that are endemic to the Pribilofs. We also made friends with the fishermen sharing the harbor with us and celebrated our coldest and windiest Fourth of July ever in a modern Aleut community.

There are in fact three definitions of the “Arctic:” the Arctic Circle (66° 33” N), the timberline and the 50-degree-Fahrenheit summer isotherm. The Arctic Circle is the best known, but in terms of climate, the latter two are actually better definitions. They exclude most of Scandinavia, which is warmed by the Gulf Stream, and some of interior Alaska, Canada and Russia, but they include all of Greenland, the Bering Sea and the Aleutian Islands. Climatically, we were already well into the Arctic.

Certainly our next passage, 500 miles to Nome, felt arctic. Despite the fog, we had almost no darkness, only three hours of twilight. And despite our well-insulated boat, we slept in two layers of long underwear in sub-zero-rated sleeping bags. We were bundled in down jackets, foul-weather gear and insulated sea boots when the Coast Guard helicopter buzzed us.

Surprisingly, though, when we reached Nome itself, we discovered why most of mainland Alaska isn’t included in the 50-degree isotherm: It actually heats up in summer! Off came the layers as soon as we’d maneuvered Celeste into the dock, and we reveled in sunshine and 65-degree highs.

A generous local couple took us under their wing there. They regaled us with tales of their own Arctic voyages, of winters in Nome with the Bering Sea frozen, and of Iditarod sled-race champions they’d hosted. They took us fishing and pointed out the exact spot on the river where gold was discovered in 1898, starting the rush that created Nome. Today Nome is still a miner’s town: homemade dredging boats vacuum up rocks from the seabed and sluice them for nuggets. We shared the dock with several dredge-boat miners, and like gold rushers from the beginning, there were some hard workers and more big talkers.

Best of all, our new friends lent us bicycles to explore the vast Seward Peninsula on which Nome is just a speck. Pedaling along dirt roads, we found the hilly tundra alive with its short summer breeding season. Red-throated loons patrolled their ponds; arctic terns dived at our heads; a mother merganser fed her newborn flock. Most exciting — and high on our list of hoped-for Arctic sightings — were the four herds of muskoxen we saw. Musk oxen are a relic from before the last ice age, a prehistoric-looking creature with big horns and long, fragrant guard hair (hence the name musk ox) covering some of the warmest fur on Earth. Their range has been much reduced, and the Seward Peninsula was the only place on our voyage we could hope to see them. So it was with near disbelief that we spotted our first placid giant munching tundra plants.

Summer in the Arctic is short, so we couldn’t linger with the musk oxen if we wanted to voyage farther north. Consequently, Seth and I set out from Nome in worse conditions than we’d have liked. Beating against strong westerlies in order to round the Seward Peninsula and get into the Bering Strait was slow thanks to the steep chop that tried hard to stop Celeste dead. The strait’s ripping currents then helped us north, but they added to the already sickening motion of 100-foot-deep water and a 30-knot breeze. To add insult to injury, pea-soup fog enveloped us despite the high winds. Conditions didn’t improve for three days — we crossed the Arctic Circle still shrouded in fog and lashed by spray — until the wind clocked into the north. At first this was a relief, but the forecast called for it to build, reaching 30 knots two days later. We didn’t want to spend days beating against that, especially given the short, nasty chop of the shallow Chukchi Sea. But there was nowhere to hide. The only place was 50 miles behind us: Point Hope, a low peninsula that would block the waves if not the wind. It turned out that nothing better could have happened than our retreat. Point Hope was everything we’d anticipated when we dreamed up the voyage. At first glance, the peninsula appeared flat and bleak, with dust swirling through a modern Iñupiat village. But then we saw the blue foothills of the Brooks Range rising in the east, and the sun circling low in the sky but never touching the horizon. It brought a sense of eternity. We witnessed wildflowers flaunting their vibrant colors, ground squirrels hurrying to their burrows and a regal snowy owl lifting off from his whalebone perch. We watched thousands of gulls and terns, spotted seals, salmon, belugas and gray whales.

Seth and I also got to know some of the villagers, who showed us the deep human history of the place. Point Hope has been continuously inhabited longer than anywhere else in North America, and the modern residents have retained a traditional way of life. The last person to move out of her sod and whalebone igloo did so in 1975, and many people still use permafrost cellars to keep their whale meat cold in the summer. Racks of drying salmon lined the pebbled beach, and even smartphone-wielding teenagers described the spring whale hunt — in open sealskin umiaks propelled by wooden paddles — with enthusiasm.

So it was hard to tear ourselves away when southerly arrows appeared on our GRIB charts. But sail we did. The anchorage was an open roadstead exposed to the south for 200 miles, and as wet and nauseating as the low-pressure system would undoubtedly be, it was our only chance to reach Point Barrow.

For nearly 10 months a year, the Beaufort and Chukchi seas surrounding Point Barrow are frozen and impassable. In July, the sea ice along the coast breaks up and, if southerly winds push the pack and floes north, an alley of open water appears. In 2012, this was more a 12-lane highway than an alley, but 2013, 2014 and 2015 had colder summers, with more ice. Seth and I had watched the ice charts, satellite images and webcams closely while we were in Nome and had seen the ice stick stubbornly to the shore. The northerlies we’d had while at Point Hope had kept it there: The one other pleasure craft we’d met — a big motorsailer in Nome — had emailed us to report getting badly stuck in 70 percent ice near Barrow. We’d also been in touch with Jimmy Cornell, bound on his Northwest Passage transit, who reported similarly. But these strong southerlies, we hoped, would push it off.

Ellen and Seth ran with a husky dog team over the tundra outside Barrow.

This time, we left in the calm before the storm and motored through glassy water. We passed the cliffs of Cape Lisburne where the Point Hope Iñupiat harvest seabird eggs by dangling on ropes. The place was teeming with murres — thousands upon thousands — one of the awe-inspiring sights of an Arctic summer. Then low pressure overtook us and we had yet another taste of the white-crested chop that comes with high winds and a shallow ocean. Two days later, we successfully rounded Point Barrow, the northernmost tip of the United States, at 71.4° N.

We were lucky: The ice had retreated as we’d expected, and the strong winds moderated just long enough for us to navigate the 8-foot-deep entrance to Barrow’s lagoon. Once inside, it wasn’t long before we made friends with the locals; ours was the only sailboat they’d seen all year, and possibly the only one ever to make Barrow its destination rather than a place to scrounge for fuel for a Northwest Passage transit. Very soon we were running with a dog team on its summer exercises, playing on ATVs and exploring the endless tundra.

On a tip from a scientist, we took a day to sail north to the polar pack ice and look for walruses. We didn’t find any, though we did see gray whales and ringed seals. But my strongest impression was of the ice itself. Seeing the ocean in a frozen state filled me with a sense of awe. The uplifted and twisted shapes of pressure ridges marched into the distance as far as we could see. White, foamy floes drifted all around us, and as we approached even closer, I could hear surf breaking as the liquid swell met the solid Arctic ice cap.

One day the National Weather Service announced that the sun would set that night. It would rise less than an hour later, but it marked an important transition. Then, a week later, great flocks of birds darkened the sky, and we knew it was time to leave the Beaufort Sea and head south. Black brants, white-fronted geese and long-tailed ducks gathered by the thousands on tundra ponds to begin their own southerly migration. So as soon as a moderately hopeful forecast came over both the VHF and GRIBs, we weighed anchor.

The rhumb line back to Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians was a little over 1,200 miles, but we must have sailed a good deal more. At first, we could lay a course to the Bering Strait, and we flew along, averaging 8 knots before a ripping northeasterly. This time we could actually see the famous waterway: The Diomede Islands — one American, one Russian — and St. Lawrence Island were wreathed in cloud. Then the wind came south and we ceased to make headway on our course, so we hove to. When the breeze came southwest, we made two long tacks to reach Nunivak Island, where we planned to wait out the southerlies at anchor. But that was not to be: A northwesterly drove us out of the exposed anchorage, only to clock back into the southwest at 35 knots. Fortunately, we’d made enough westing to be able to reach for a day without hitting land; then finally the wind came north again and let us lay our course to Dutch Harbor. On the last day, we forgot all our travails as we dropped off the continental shelf and regained the long, smooth swells of deep water. Before we knew it, we were back in Dutch, snug among the Deadliest Catch boats and already reminiscing about the Arctic.

Was it crazy? Probably. But we’d witnessed the Arctic Ocean from the deck of our own little sailboat, seen rare birds and animals, learned about Iñupiat culture and run with a dog team. In the end, not a bad way to spend the summer.

Ellen Massey Leonard has a new video channel! Watch Ellen and Seth’s adventures at Gone Floatabout.