AIS Delivers News You’ll Use

A typical VHF Broadcast:

“This is the sailing vessel Three Blind Mice, WXY-1234, located at 41 degrees 03.20 minutes north, 71 degrees 24.86 minutes west, on a course of 272 degrees magnetic, to the northbound commercial vessel approximately 5 miles off my port bow.”

“They still won’t answer?” asks the skipper. “How many times have you called them, anyway?”

“This has got to be the fourth or fifth time in the last half an hour,” replies her trusty mate.

“OK. Since they’re not listening to the radio, we can only assume nobody’s on the bridge right now. Let’s change course and get out of this guy’s way.”

Anyone who’s sailed offshore has probably had a conversation like the one above more than once. You may have the best radar unit in the world or the finest binoculars, but neither will tell you the name of the vessel you’re seeing or where it’s headed. While not intended for the recreational sailor, the Automatic Identification System, which has been made mandatory on all seagoing ships over 300 tons, is a boon to those of us who share the sea with commercial vessels. With a simple, inexpensive AIS receiver, you can “see” commercial vessels on your chart plotter, navigation software, or even on a small display screen; these commercial ships can be as far as 30 miles away, even around points and bends in a channel that radar can’t see. You’ll be able to learn the name and radio call sign of the vessel, its cargo and where it’s bound, what its rate of turn is, and how fast it’s going over the bottom.

Marine-electronics and navigation-software companies have realized that AIS is an important tool for recreational boaters. While there’s a plan to develop a B version of AIS for the pleasure crowd-even small boats would have AIS transceivers sending and receiving position data-everyone understands that even today’s “dumb” receivers are a great way to provide boaters with crucial navigation data right now.

Because the technology is relatively simple and uses hardware that has become readily available, it’s not hard to integrate AIS into your electronics suite. AIS signals-which are digital, and as such, have better range than analog VHF transmissions-are broadcast on VHF channels 87B and 88B.

While the technology may be simple, there are still issues to consider if you’re buying an AIS-enabled receiver. For instance, debate continues on whether a VHF antenna should be shared between an AIS receiver and a VHF radio. Some companies are supplying signal splitters with their AIS receivers, so if you have two VHF radios aboard, the radio that shares the antenna with the AIS unit should probably be your backup set. Raymarine’s AIS250 receiver module, for example, uses a signal splitter. Other companies, including SeaCAS, one of the first to market AIS to the recreational-boating market, have decided that AIS works better with its own dedicated antenna. To help reduce the clutter aloft, SeaCAS offers a dual GPS/VHF antenna for its AIS system. “Using an antenna splitter isn’t recommended because it prevents you from receiving AIS position updates from a vessel while you’re using your voice VHF to make passing arrangements,” says SeaCAS founder Fred Pot. “The antenna splitter will reduce the sensitivity, or range, of both your voice VHF and your AIS receiver by 3.5 decibels.”

Once an AIS signal is received by the antenna, it’s sent to a black box that translates the data into NMEA streams that can be sent at 4,800 or 38,400 baud. The lower baud rate works with electronics suites still using the NMEA 0183 communication protocol; the higher baud rate works with proprietary networks, such as RayMarine’s, and devices using the more capable NMEA 2000 communications protocol.

Displaying AIS data can be done in three ways. The first and simplest way is with a small display that looks like a simple Automatic Radar Plotting Aid radar screen, showing the ranges and bearings of targets relative to your boat, with a vector line showing their courses. Each target’s AIS details will also be available in a tabular form. The display, with ranges between 1 and 32 nautical miles (about the maximum range of a line-of-sight VHF transmission), shows ships as you’d see them on a radar screen. Data taken from your boat’s GPS puts your boat at the center of the display. All other AIS-equipped vessels are shown with ranges and bearings relative to your boat.

You can also add AIS data to an existing navigation system that uses plotters and/or radar screens, including RayMarine’s C and E series, Furuno’s NavNet systems, and the Simrad system, among others. These systems all have multifunction displays that can include AIS information as an overlay.

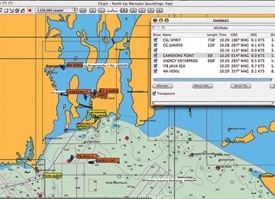

The third and perhaps most elegant way to use AIS data is with most any of the navigation-software programs available today. Unlike AIS data overlaid on a plotter, AIS data brought into a navigation program can be manipulated. I’ve had a SeaCAS AIS 300 dual VHF/GPS antenna rigged on an old carbon sailboard mast attached to my house in Newport, Rhode Island, for most of the winter. Because we’re located within a mile of Narragansett Bay, I’ve been watching shipping go in and out of the bay and seeing how the various programs interface and display AIS information. Thanks to processor power and smart software, it’s possible to assign different colors to different vessels, search for ships by name, and, if the vessel’s specifications have been input properly, see a properly scaled version of the vessel on the chart.

Systems from Raymarine, Furuno, and Simrad all have the AIS capability to help you safely share the water with commercial vessels transmitting AIS information. Those familiar with such radar acronyms as CPA (Closest Point of Approach) and TCPA (Time to Closest Point of Approach) will doubly appreciate AIS because it takes the guesswork out of radar by providing you with a vessel’s name, type, and Marine Mobile Service Identification number. For details of what’s included in an AIS transmission, go to www.cruisingworld.com/0507ais

As helpful as it is, AIS information needs to be taken with a grain of salt. There are certain areas of the world in which merchant skippers don’t particularly want to be read like a book. Captains in areas where pirates have been known to attack routinely shut off their AIS transceivers. Military vessels, including U.S. Coast Guard units, will most likely not be sending AIS data, either, for reasons known only to the folks at Homeland Security. Fishing vessels, unless they’re large factory vessels, won’t be sending AIS data because most of them are well under the 300-ton minimum mandated by SOLAS, the international convention for Safety of Life at Sea.

Then there’s the garbage-in/garbage-out theory. The U.S. Coast Guard recently issued a reminder to commercial vessels that use AIS that they need to update their data to accurately reflect their present voyage.

Still, when you encounter a ship at sea, any news is better than no news when it comes to making sound navigational decisions.

Tony Bessinger is CW’s electronics editor.