Part 3: Monday, July 13

“The dream is dead,” Billy told me, midway through our shared watch in the wee hours. Logan had devised a watch schedule where we all shared an hour with each other every evening. By now I was getting used to Billy coming up with some pretty interesting post-midnight observations; still, this one caught me by surprise. As did this, a little later: “When the horse expires, it’s time to dismount.” It was pretty clear Billy was considering bailing out and turning around.

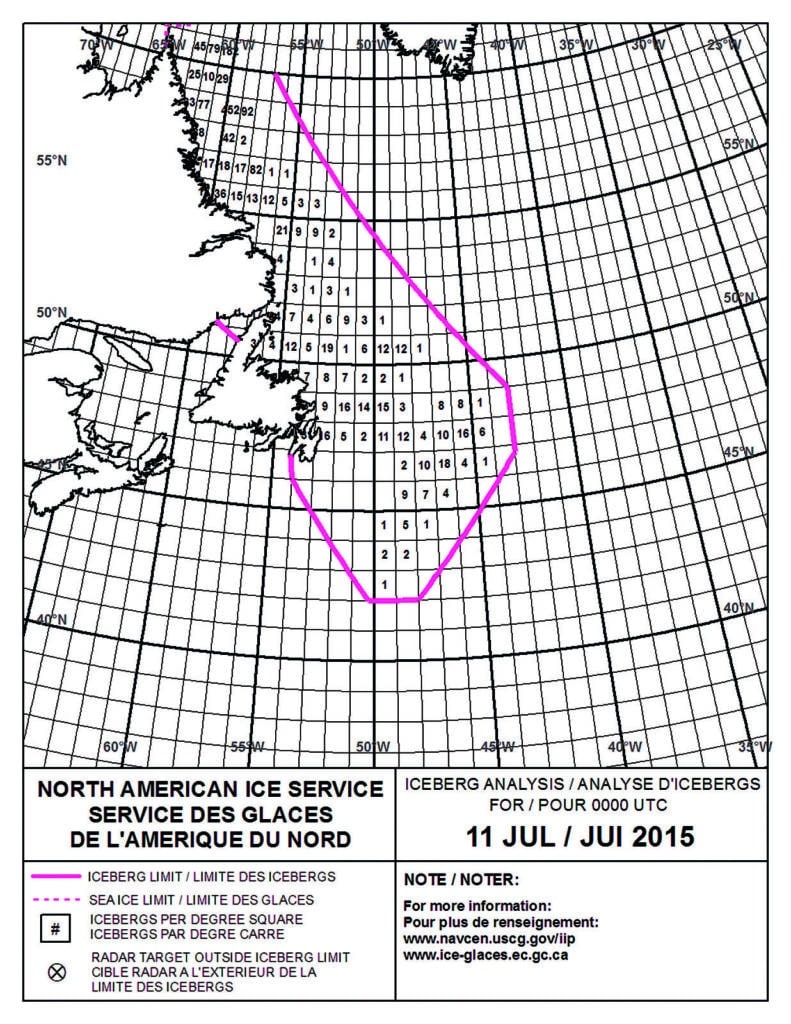

Like all of us, especially Logan, Billy’s consternation stemmed from the growing list of problems aboard Eleanor. At the moment neither the radar nor the AIS system was operable, and we’d discovered that the electronic charts for the waters we were currently sailing, and the countries we were headed for, hadn’t been loaded.

A call to Front Street a few hours later cleared up the technical issues; apparently, when the new arch had been installed, not everything was hooked back up. Emerging from the depths of the boat after getting things sorted, Logan said, “I feel like I climbed Mount Everest. It’s a scary place down in the bowels of these machines.”

The biggest issue, however, was with the rebuilt generator and the electrical system. With increasing frequency, the circuit breaker for the generator was cutting out as soon as we switched the thing on. Annoyingly, the reset button was buried behind a panel at the bottom of a cockpit locker loaded with heavy-duty anchors and ground tackle. And other breakers on the aging main electrical panel began popping as well.

Why?

We didn’t know.

Still, I told Billy that folks like Lin and Larry Pardey had crossed countless oceans with absolutely none of the things he was fretting about. We could too. Some of Eleanor’s systems were suspect, true. But she was a superb sailboat, strongly rigged, with a very complete and excellent sail inventory. That didn’t seem to reassure him. Even if we got to Scotland, he said, he wasn’t sure the work could be completed correctly. And even if it was, it would cost a fortune.

It didn’t make sense to argue with him, so when it was time to rouse Logan and hit my bunk, I bid Billy adieu half-expecting I’d wake up to find us heading west, back toward Maine. Lo and behold, when I arose a few hours later to what turned out to be an interesting day, we were still on course for the British Isles.

The weirdest part of it happened when I was snoozing. Apparently, Logan and Billy were approached by a pair of dudes in a 25-foot center-console powerboat with a single outboard — not something you’d expect to find in the open Atlantic 100 miles off the coast of Nova Scotia. They came alongside, mumbled incoherently, dropped back, shone a light on the hull, approached again and asked, “Where’s Lyle?” Then they bolted off for good. Logan reckoned they were harmless nuts, that it was some sort of botched drug rendezvous. But it remains a mystery.

When Billy told me the story a few hours later, he confided that the situation had been under control, but that if things had gone awry, we were packing heat anyway — we had weapons aboard. To be honest, this didn’t surprise or even faze me all that much. Billy’s a Texan, after all, and we’d had arms aboard Ocean Watch; Canadian law requires them in the Arctic to protect against polar bears. But it’s something I’d really have appreciated knowing from the owner prior to setting sail, before we were involved in some sort of crazy cowboy crap with a boatload of clowns in the North Atlantic.

The next bit of drama was of my own making. Midmorning, I swapped texts with my girlfriend on the Iridium Go! unit and received some highly disturbing news about our relationship and the tenuous nature thereof. To say that I’d been a distracted, annoying boyfriend would be an understatement. Indeed, here I was again, off on my own trip. So it probably shouldn’t have been a surprise. What I should have done was call her then and there; God knows we had enough phones on board. Instead, I texted back some “nasty-grams” and left it at that.

Being at sea with a clear mind is one of the greatest joys of life. But when things aren’t so hot, and you have endless time to ruminate, the sea can be your mind’s prison, a horrible place to inhabit. I admit, I was shaken. Over the next couple of days, I’d even make a couple of highly uncharacteristic sailing errors, which shocked me. I couldn’t tell if I was heartsick, preoccupied or just plain stupid. Whatever the case, it wasn’t good. If I’m not contributing a top level of sailing performance at all times, frankly, I’m not bringing much to the party except a lot of bad jokes. I had to snap out of it.

I did find solace in the beauty surrounding us. We saw countless whales, including a pair mating that we damn near ran over. There were porpoises, sharks and even a couple of velellas, the jellyfish sporting exquisite white “sails.” My close mates, especially Hasse, were of great comfort. My favorite hour of every day was the one she and I shared in the mornings before dawn, when she patiently gave me an impassioned astronomy lesson, pointing out the constellations and telling me the stories that connected them. And every moment of every day, sailing with Hasse, you learn volumes about the balance of fine sail trim, and by extension life itself.

And of course there was the sailing. God, I love sailing.

By midafternoon we were broad-reaching under working sail in a failing breeze. The barometer had started falling for the first time; the crystal-clear skies were giving way to high cirrus clouds. I suggested setting our asymmetric kite and got a raised eyebrow from Logan. But Hasse is always game for hoisting more laundry, so I dragged the big sail up on deck. Soon enough, it was up and drawing, and our speed had increased from less than 4 knots to more than 6.

“I hate it when you’re right,” Logan said — an extremely rare occasion.

Hasse was keeping a meticulous ship’s log and made this late-afternoon entry: “Feels like trade-wind sailing. Amazed at the warmth. Watching contrail movement.” The weather was definitely changing.

As the sun set in our wake, we carried the kite onward into the night.

Herb McCormick is CW’s executive editor and the author of As Long As It’s Fun, the award-winning biography of Lin and Larry Pardey.