I upgraded from Second Wind, a 35-foot Bavaria Cruiser, to Beckon, a 39-foot Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 39i Performance, in anticipation of cruising the Caribbean for a year or more. My home base is Puerto Rico, and Beckon was in Southwest Harbor, almost as far north in Maine for sailing as you can get. My friend and Jeanneau broker, Francis Shiman-Hackett of Bluenose Yachts, enticed me to sail the coast of New England for the summer, then head south in November after the hurricane season.

Little did I know that I wouldn’t even get out of Maine before learning some important lessons about being careful and resourceful as a singlehanded cruiser.

I departed just after Memorial Day under an unusually bold, sunny sky, with flat seas and scant wind. The mild conditions allowed me to work out the kinks of sailing a new boat. Beckon has electric winches, a self-flaking system, a sizable forward cabin with stowage, and solid navigation instruments. It has a taller mast and longer keel, which gave it the performance designation. All of this was great for me as a solo sailor.

There was not another sailboat to be seen on the 14-nautical-mile motorsail to lovely and protected Swan’s Island, where I picked up a mooring ball, as well as a lobster for dinner from the Fisherman’s Co-Op. The next morning, I motorsailed southwest against a prevailing but mild southwest wind, intending to anchor in Long Cove on Isle Au Haut for the night.

Because it was a cold, cloudy day with little to do on anchor, I pushed past the island and bypassed Vinalhaven Island, seeking a mooring at Tenants Harbor, which is full of lobster boats. By midafternoon, I calculated that I would reach the harbor at dusk—not ideal for an unfamiliar anchorage. My new plan became Home Harbor, located between Pleasant Island to the south and Hewett Island to the northeast, reachable with daylight hours to spare. It’s more of a bay than a harbor, and it’s protected from southwest winds, but the Hewett Rocks ledge was directly in my course heading. I sailed past the rocks at midtide, and a late-afternoon sun peeking out of the clouds illuminated their rugged beauty and dangerousness.

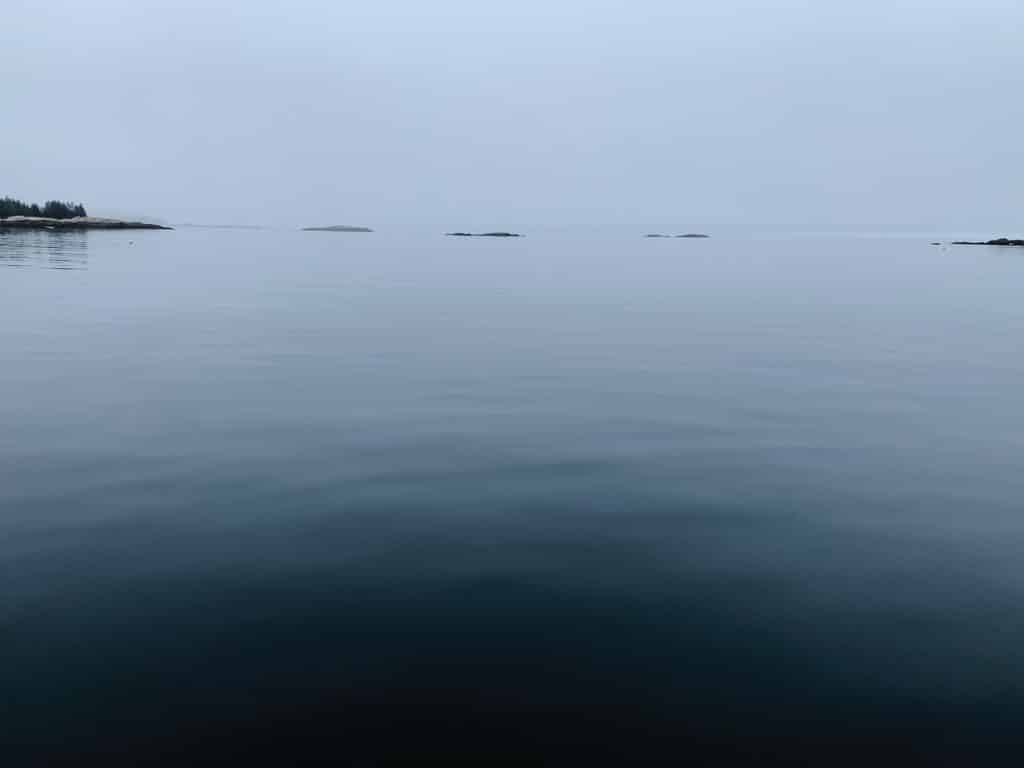

Once inside the tranquil bay, I dropped anchor in 16 feet of water. I am used to the sand bottom of Caribbean anchorages with no tidal range, so I tested my setting twice with hard bursts in reverse. I felt confident that I was securely set. The water was glass, the air was crisp, there was no movement to the boat, the late afternoon sun was bright, and the panoramic background was dramatic, with pink and white clouds ringing the horizon. Smooth and jagged rocks formed the shore. I thought that I would sleep safely and securely, and saw no need to use an anchor alarm. After dinner, I fell hard asleep in my V-berth.

At 1:30 a.m., I heard the screech of my carbon-monoxide alarm. Then I heard the unmistakable sound of my anchor dragging—not an occasional drag, but instead a constant, loud stuttering. I donned my cold-weather jacket and pants, turned on my navigation instruments, and raced up the companionway shoeless.

I was stunned to find myself in pea-soup fog and air full of cold, thick mist in pitch-black darkness. I could not tell where I was, but my depth sounder showed 16 feet. I felt temporarily relieved, deducing that I could not have dragged far.

Then I heard the water sway against what I thought was the rocky shore of Pleasant Island. I went below and grabbed my high-powered spotlight. It only emphasized the cold-water mist. Visibility was mere feet. I could see neither land nor shore, though I kept scanning 360 degrees.

I went below again, this time to fetch Navionics on my iPad. I could not find my location in the bay. I moved the chart in a circle to find my position, and I was horrified to find that Beckon was within feet of Hewett Rocks, the very ledge I had avoided the previous afternoon. I had drifted some 300 yards. I kept scanning with my light and finally saw the jagged rocks within feet off the port side of Beckon.

With keys already in the ignition, I fired up the engine. I went below to turn on my windlass, leaped back up the companionway, and walked forward on my starboard side deck, one hand holding the light and the other holding the lifelines. I did not take my thumb off the windlass remote until the anchor violently shook in its cradle.

Navionics seemed to suggest that Beckon was parallel to the rocks. I did not know whether to go in forward or reverse, but I needed to make a quick decision. With one hand on the wheel and the other holding my light, I chose reverse.

The question then became: How do I get back to the anchorage? After I reached sufficient depth, I took the protective cap off my binnacle compass. I stayed in reverse until I felt comfortable that I was a fair distance from Hewett Rocks, then I put Beckon in forward.

Slowly, I tried to connect the compass heading with the red arrow on Navionics. I could see nothing in the fog and darkness, but I knew that my only impediment to reaching the anchorage was a handful of lobster buoys.

There is a lag in the movement of the arrow on the screen following a course change with the wheel of the boat. During daylight, it becomes a part of how you drive, but in darkness, it was an almost insurmountable barrier. I tried to go southwest, but I continually overcorrected and was heading in a circle back to Hewett Rocks. More reverse. I did this several times before I started getting the hang of how to navigate by compass in the dark.

I was horrified to find that Beckon was within feet of Hewett Rocks, the very ledge I had avoided the previous afternoon. I had drifted some 300 yards.

Still, I seemed to be going in circles. I was trying to drive to the middle of the bay, but I found only the northern part, too close to the rocky shoreline. It took me the better part of an hour to find the middle. With my light, I kept seeing the same two orange-and-white lobster buoys, sometimes to port, other times to starboard. I thought that if I woke the residents of the nearby homes, they would think a crazy sailor was doing doughnuts in the bay in reverse with a searchlight.

I dropped anchor in the southeast corner of the harbor, very close to the shore. I could see the outline of the rocks with my light and thought that I was perhaps 20 feet from land. I weighed anchor and tried again, finally closer to the middle of the bay, and right next to the orange-and-white buoys. How I did not drive over any lobster buoys was beyond me.

My anchor did not set well. I dragged, but I was in a decent location. Fifth time’s the charm, I told myself. Exhausted, I decided simply to watch it.

I went below and looked at my phone. It was 3 a.m. I had to laugh at myself—I had narrowly avoided disaster on Day Two of my journey. But I had done it, and done it on my own. I briefly thought about making coffee; instead, with my jacket and wet clothes on, and with frozen feet, I collapsed in my V-berth, face up.

It did not hit me until I woke, when I looked at the chart again, that after my anchor dislodged, I drifted over 49 feet of water depth. My anchor reset, to a degree, in 16 feet of depth next to Hewett Rocks, all while I was sleeping soundly. Was I within minutes or more of crashing against the rocks? And why had the carbon-monoxide alarm triggered? Perhaps it was something divine or a warning from the universe.

The obvious lessons from this experience are to let out sufficient rode and to account for the tidal range. In that part of Maine, the tidal range is 10 feet. Sixteen feet at midtide, when I arrived, meant that high tide would mean at least 21 feet of depth, which requires a quite different calculation on anchor scope.

I was seduced by the beauty and serenity of that bay. In coastal Maine, conditions can change in minutes, and fog can roll in like a sandstorm without warning or forecast. So, set an anchor alarm, no matter the initial conditions. A captain I met on Mount Desert Island suggested keeping the GPS on and waking yourself at midnight to check your position. Had I done so, I could have seen my tracks and followed them back.

Overall, if you are going to cruise solo, be ready to rescue yourself. Another sailor would have navigated the compass and chart plotter in the dark much more effectively than I did.

The morning after my almost disaster, and after the heaviest of the fog had lifted, I motored the 6 nautical miles to Tenants Harbor and saw only the occasional lobster boat. I picked up a mooring ball and slept like a rock that night.

In the early-morning hours, my carbon-monoxide alarm shouted at me again. The illusion of a divinely inspired intervention disappeared like burned-off fog. I ventilated the salon, reset the alarm, and went back to sleep.

The final lesson learned is to keep the batteries in your carbon-monoxide alarm up to date. That alarm can save you in more ways than one.

Damian LaPlaca is currently in Puerto Rico aboard his Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 39i Performance, Beckon.