I have no problem being called a traditionalist sailor. I wouldn’t have made a brigantine schooner if I wasn’t. But that doesn’t mean I haven’t embraced some technology that has swept like a hurricane through the boating world, particularly in the area of electronics.

Undoubtedly, many of these modern inventions have made boating much safer and more enjoyable, but they have also created a dependency on the gadgets themselves. Far too many boaters are failing to learn and use the methods that have served, and many times saved, seagoers for centuries.

GPS, without a doubt, is the greatest innovation in the past 40 years. It might rival the invention of the wheel. Even so, I still mark our paper charts every hour because, if power is lost, the chartplotter will conk out.

I still use a lot of other traditional sailing tools, too.

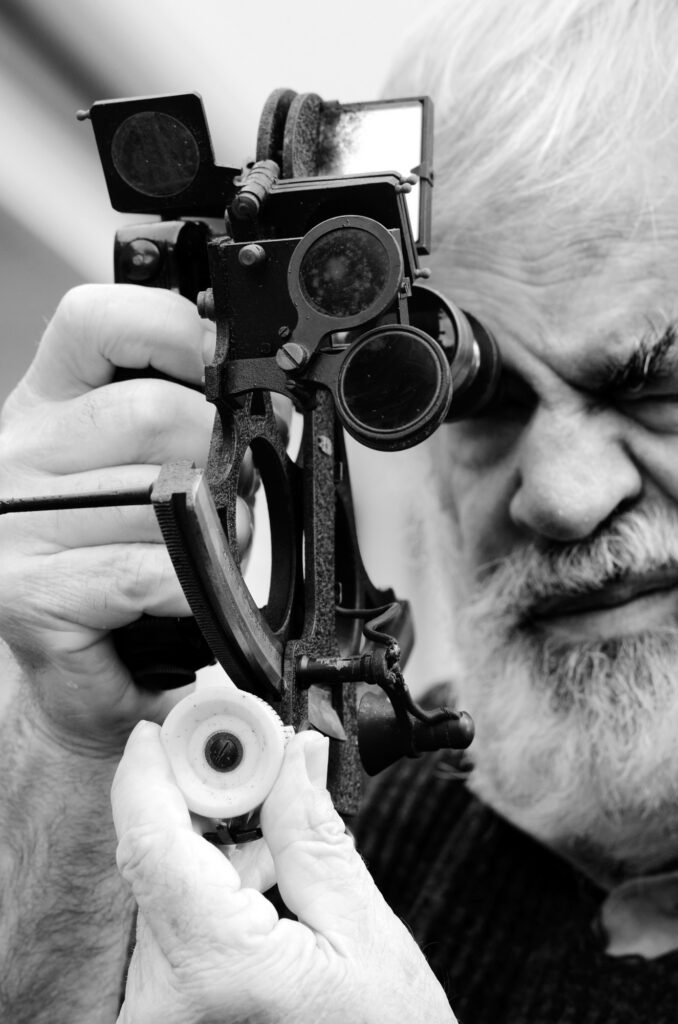

The Sextant

Only two satellites had been launched when we bought our first sailboat and set sail south, leaving England by the lee for our great Mediterranean adventure. There was a 12-hour delay in obtaining a position, which was not much use on a boat traveling at only 6 knots.

That’s why we learned celestial navigation with a sextant. I would take the sights, while my wife worked out the math and marked the chart. After four days of crossing the Bay of Biscay, we made landfall on the nail at Cape Finisterre on the tip of Spain. We felt a great deal of satisfaction in this achievement, and that same sextant still sits in its teak case on my latest boat, nearly 50 years later. Britannia’s sextant. There are other uses for a sextant as well, such as calculating the distance of an object like a lighthouse, but all have been superseded by the miraculously accurate GPS, with which we once navigated into the port of Oporto in Portugal in a dense fog and never hit anything either.

Still, if GPS failed the great majority of the boating public, I suppose they would pull out their mobile phones. They probably don’t even know what a sextant is.

Depth Gauges

My boat’s hull-mounted electrical depth gauge is nonfunctional at the moment, because of growth over the fitting. Britannia is also moored in the Intracoastal Waterway, which is shallow nearly everywhere and extremely shallow in some places. Some form of depth gauge is most advisable.

There are two substitutes for a depth gauge: a handheld, battery-powered device that’s a bit like an electric shaver and that needs to be held in the water to give a reading. On Britannia, this would need to be strapped to a boat hook to pass down over the 4-foot freeboard.

The other option is the classic lead line, which is accurate when set up and used properly, and can even tell you the nature of the bottom if you are about to anchor. And the beauty is, it’s never subject to power failure.

Bilge Pumps

Electric bilge pumps can automatically empty a bilge. They are ideal for a boat that is not regularly sailed, but the operative word again is electric. The boat’s batteries can run down, the pump can clog up, the float switch can fail to activate the pump, and so on.

As a backup, Britannia has a high-volume diaphragm pump operated from the cockpit. It empties a normal bilge level in a few manual strokes, and we often use it when we first get on the boat. It also has a manually activated 120-volt high-volume sump pump, which works from the dedicated generator battery.

A small bilge can also be emptied using a manual suction pump. And there’s always a bucket.

Steering

Most boats over a certain size have wheel steering, which usually communicates with the rudder by way of hydraulics. They’re easiest for manufacturers to install, and they only need an oil pump on the wheel, leading by hoses to a ram on the rudder stock.

Another method of steering uses cables running from a cog and chain on the wheel spindle through cables and pulleys to the rudder quadrant. Neither of these methods employs electricity, but they are not by any means failure-proof. Hydraulic fluid can leak out of the pump or the ram, and leaks can occur over time from badly installed pipes.

The pulleys needed for cable steering can corrode or jam from a lack of oil, but there is a certain peace of mind in knowing that a properly maintained cable system physically turns the rudder. And there’s always a tiller that acts directly onto the rudder stock, making it wise to have one aboard as a backup.

Autopilots

A hydraulic or electric autopilot needs an electrical supply. Hydraulic autopilots use an electric pump to circulate the fluid to operate the hydraulic ram that moves the rudder. There will also be a rudder angle gauge and a control box, also electrically powered. Britannia’s is an amazingly accurate device, and it has never failed yet.

But that’s because I treat my battery banks like a newborn baby, and I am conscious of power consumption when the autopilot is on but the engine is not.

Many cruising boats that ply the ocean trade winds use a wind vane mounted on the stern. It requires no auxiliary power whatsoever and keeps running forever—so long as there is wind.

Another backup that needs no power, except feeding from time to time, is called a helmsman.

Lighting

Britannia has LEDs, including for the long-range navigation lights. These LEDs use less than one-quarter of the power of a regular bulb and are just as bright, so long as the electrical power remains.

I have lived aboard with auxiliary oil lamps in the saloon and staterooms, in case of a power failure, but these lamps can be quite dirty if they’re trimmed too high or if they lack a heat shield over the flame, which can scorch the ceiling. They also require the storage of kerosene as fuel.

Charts

Paper charts are difficult to store and read in a cockpit, or on a small chart table. I still want them anyway.

On every ocean passage we make, the chart is spread out over the saloon table and marked every hour (more or less) with coordinates from the plotter. This will give us a fix if there is a glitch in the chartplotter.

It’s also a keepsake. Without such a record, a passage becomes just a means to an end with nothing to remember it by. Our most recent passage, 530 miles from Cape Canaveral, Florida, to North Carolina, is now a framed picture on our wall at home.

Fresh Water

Freshwater hose connections can be seen attached to many boats in marinas, especially if people are living aboard. Such a simple pedestal hookup has some advantages. The constant pressure saves using the boat’s water pump, and usually gives a greater and more even flow to faucets and showers. It also saves the batteries and is a silent operation.

But if a water pipe breaks or a connection fails, sure, the bilge switch would activate the pump, but the powerful rush of water would probably overpower the pump, with possible catastrophic results. This actually happened to me once. If we hadn’t come back within a few hours, the boat would have sunk.

I devised an idiot-proof (that would be me) backup using a water shutoff solenoid and a latching relay, which is just like a normal relay, except it stays activated even when the power source is removed. The solenoid is fitted in the boat’s inlet line and closes when the bilge switch activates it. Then, the latching relay keeps it closed, even when the bilge switch returns to an open circuit.

It’s a simple and worry-proof solution.

Parting Shot

Out on the water, especially on the open ocean, things can go wrong fast. Electronics and seawater don’t mix, and it is not possible to pull into a rest stop and call for assistance. It’s just plain common sense to have a backup available for the more important items, just like having oars attached to a dinghy in case the outboard fails.