Not long ago, a client told me that the diver who routinely cleans her sloop’s bottom and changes the zincs was reluctant to install the aluminum anodes that I had recommended. He told her that they would cause, rather than deter, corrosion.

This isn’t an unusual occurrence for me. Often, a well-meaning industry professional—who might be quite experienced in a certain field but otherwise has no formal training whatsoever in corrosion analysis—tells a boat owner something that could have a lasting effect. In my experience, corrosion is far and away the most misunderstood, and most misdiagnosed, phenomenon within the marine industry, with electrical-system issues a close second.

When bad information happens to my good clients, my goal is to educate rather than denigrate those who are misinformed. I’d rather create acolytes than enemies.

Electrons and Ions

Long ago, a corrosion mentor of mine taught me one of the most effective techniques in bringing misconceptions to light. He taught the American Boat & Yacht Council’s corrosion certification class, and when he was faced with an incorrect corrosion analysis, he would say, “OK, using a pencil and paper, draw a diagram showing the path taken by the electrons (which travel through wires and metal) and ions (which travel through water).”

If the individual being challenged could not accomplish this, then the theory would have to be questioned, if not dismissed. As a vessel owner, you too can use this approach with anyone trying to tell you something about corrosion analysis.

Leave Well Enough Alone

This isn’t the first time I’ve heard the line about how changing anode materials will cause corrosion. I believe that some of this thinking is due to concern that if any type of professional—divers, technicians, boatbuilders—recommends or endorses a change and corrosion does ensue, then they will be held responsible for potentially costly damage. They fall back on “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” to cover their tushes.

My opinion is that while change for the sake of change isn’t a good idea, change for something that works better should obviously be embraced.

ANODES, ZINC, MAGNESIUM and Aluminum

Let’s get back to my client and the diver’s advice that conflicted with mine. If the anode material was magnesium, and it is in seawater, then with a caveat, yes, the diver would be correct. Magnesium anodes should be used only in fresh water. In seawater, they are too aggressive, with the caveat being that overprotecting the metals typically used on the hull of a fiberglass sailing vessel is not harmful to anything other than antifouling paint. Overprotection can cause paint to separate from protected metals and the adjacent area.

Zinc and aluminum anodes, on the other hand, are well-suited for seawater applications, while aluminum anodes are one-size-fits-all because they can be used in seawater, brackish water and fresh water. They will provide proper protection, and paint will not be affected.

The diver is, therefore, incorrect. Aluminum anodes will not be harmful, and they will protect underwater metals. That’s why aluminum is my anode material of choice.

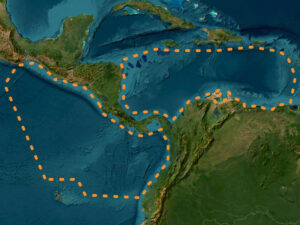

While the cost of anodes varies with the value of the respective metals, typically, aluminum anodes are the same—or nearly the same—cost as zinc anodes. They are especially well-suited to scenarios where a vessel might be in seawater as well as fresh or brackish water—say, moored in tidal estuaries or behind locks.

Zinc, when used in fresh and brackish water, develops a buff or brownish coating that essentially causes it to go dormant, providing no protection. The coating can be removed with a stiff-bristle nonmetallic brush, but doing so might be inconvenient.

The bottom line is: Follow the electrons and ions, and choose your anode material carefully.

Steve D’Antonio offers services for boat owners and buyers through Steve D’Antonio Marine Consulting.