Confession: I have an irrational fear. Not of heavy weather, but rather of having salt water back-siphon into my vessel’s diesel engine. Weird, right?

Actually, not so weird. On new diesel installations, I’ve found that a common cause of premature engine failure is exhaust-related.

Thus, a decade or so ago, when I installed a brand-new Perkins M92B in our 43-foot ketch, Ganesh, I paid careful attention to its exhaust system. I not only repeatedly rubbed it with hundred-dollar bills, but I also consulted various marine engineers and exhaust experts, including “Diesel” Dan Durbin, formerly of Parts and Power on Tortola, the guy who wrote the excellent “Please Don’t Drown Me” technical paper for Northern Lights.

I’m totally anal about my exhaust system. For example: I have a custom drain on my marine muffler (Centek Vernalift) so that I can empty it during severe gales, or at least monitor the water level during extreme weather or after a 360-degree roll. Not only that, but the large exhaust hoses going into and out of that Centek muffler are different sizes at different points to reduce back pressure. And, yes, I’ve physically tested the back pressure in my system to make sure it is within spec.

Even better, I have a water-exhaust separator (also Centek) mounted high up in my engine room, a setup that allows the raw water to flow out independently of my exhaust fumes. That’s right—my exhaust gases exit through one through-hull, and my exhaust water through another.

Why so complicated? Because I am a poor man who sails in rough water with empty pockets, and I need my exhaust system to be bulletproof. It is much harder for a hose without salt water to allow salt water to back up into your engine than it is for a hose that contains salt water.

Notice I said “much harder” but not impossible? That’s because nothing is really impossible for a determined, malevolent water molecule—nothing.

Anyway, the good news is that my system has worked perfectly, often in extreme weather conditions, for more than a decade and 50,000-plus ocean miles. The littlest details of seamanship matter most. For example, I always check my engine’s fluids before cranking up, and I always check the raw-water flow after cranking up. Always. (Well, except once in 62 years.)

Here’s a quick overview of marine exhaust basics: There are two types. The hot-exhaust type is excellent at not allowing any salt water to back up into the engine, but the whole system is red-hot and often inadvertently catches the boat on fire; so often, in fact, that hot exhausts aren’t allowed on certain charter boats. They are just too dangerous on passenger-carrying craft. Fire at sea can be almost instantly life-endangering.

It is much harder for a hose without salt water to allow salt water to back up into your engine than it is for a hose that contains salt water.

Most sailboats have a wet-exhaust system where the raw (salt) water mixes with the exhaust gases just after the manifold, and the coolish water/exhaust gets pumped into a muffler where the force of the exiting exhaust fumes lifts them both up and overboard.

The problem with a wet exhaust is that there is always the possibility of water backing up and getting into the head of the engine. This often results in catastrophic failure of the engine—and, as a bonus, mental breakdowns among the boat’s owners.

Which brings us to two days ago. I was waiting for a crowd of Singaporean friends to come aboard to go island-hopping with us. They were slightly delayed. I checked the fluids in my engine, carefully eyeballed it, cranked it up (it started perfectly), and immediately visually checked its raw-water output by leaning over the side of my vessel. The raw water was pumping overboard just fine. Oh, what a good boy am I.

I ran my engine for a couple of minutes to allow it to come up to temperature, and then shut it off. During that time, I heard a clink, which I thought was something rolling off the cockpit table onto the cockpit sole. I lazily searched around the cockpit for the fallen object but couldn’t find it. (Clue.) No biggie, right?

Once everyone was aboard, I recranked my now-warm engine, but this time it did not fire up on first revolution. It cranked a bit. That was unusual. (Clue: Anything unusual is a clue.)

Hmm, I mused to myself, thinking I needed to file, sand and clean my battery cables to get rid of any building corrosion. I did not check my raw water because, hey, I’d just checked it four minutes ago. What could go wrong in such a short span of time?

Plenty.

In blissful ignorance, I yelled, “Cast off!” at my wife, Carolyn, on our bow. She dropped the mooring pennant.

All my Singaporean guests were huddled in the cockpit, thrilled to be underway on such a primitive, wild, daring-do sea adventure.

“Is this safe?” asked a fellow who had never been on such a life-endangering voyage.

“Oh,” I smirked confidently, “after three circumnavigations, I think I can get you to that placid isle called Ubin a few hundred meters ahead.”

Yes, pride always cometh before the fall.

I attempted to increase my throttle—and, to my amazement, my engine slowed. It was at this point that it occurred to my seldom-used little pea brain that I might have a problem worthy of my feeble attention. (Clue: All problems are worthy of a skipper’s attention.)

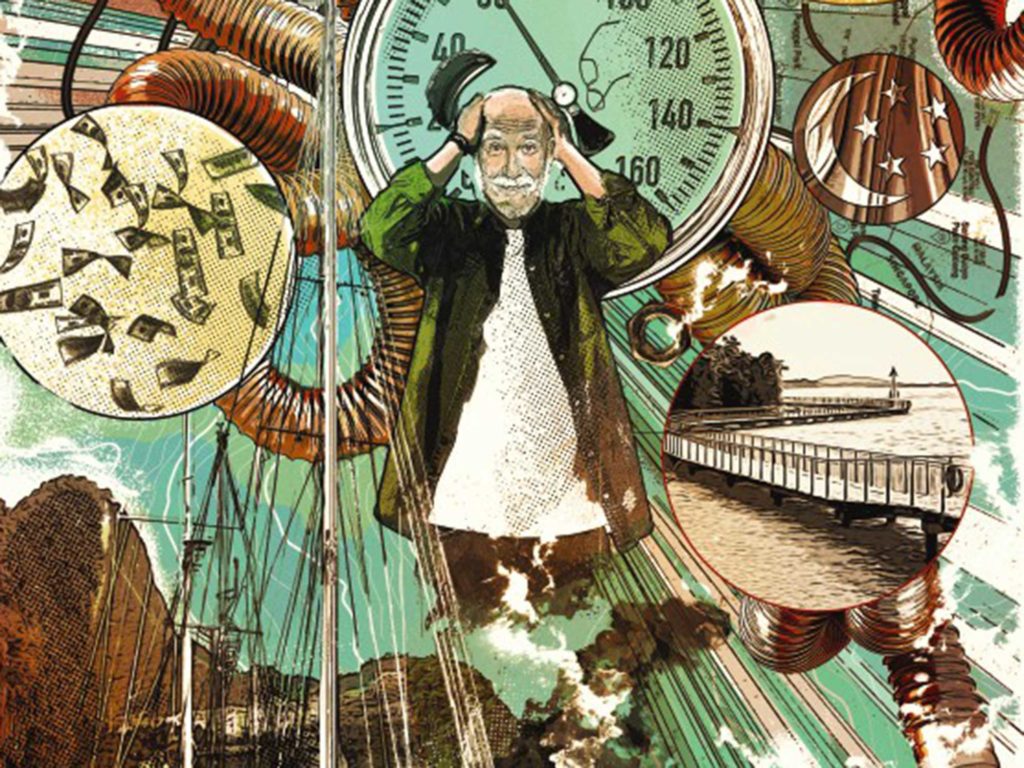

While I was scratching my head where my hair used to be, and wondering if I had a throttle linkage problem, all hell broke loose. Huge billows of thick, gray smoke started coming out of all the hatches, companionways and opening ports. Coughing people came rushing on deck, terror in their eyes.

“Fire!” someone screamed.

All this happened quickly, just as I realized my engine was losing rpm because there was no oxygen in my engine room, only smoke.

We were on fire.

Carolyn and my daughter, Roma Orion, bravely hopped below to grab fire extinguishers, but both came shooting right back out, coughing heavily and bleary-eyed.

“Poison!” Carolyn screamed. “Deadly gas!”

The situation was deteriorating quickly. Our Singaporean friends were desperately attempting to wave down a passing supertanker, screaming to be taken off Ganesh before their imminent and inevitable deaths at the hands of ocean-intoxicated, thrill-seeking Westerners.

My reputation as a respected circumnavigator was plummeting fast. I now did what I always do in emergencies: I glued on a confident smile, as if I possessed intelligence. I took a deep breath and asked myself, What the hell is going on?

I shut off my engine and ordered the crew to the foredeck (they were all coughing and tearing up from the poisonous fumes). Next, I opened all the hatches for maximum ventilation, shut off the main battery switch (by feel while holding my breath) and, back on deck, unrolled the genoa to gain steerage.

Once the engine and battery switch were off, the emergency was over. Well, except for our crying, terrorized guests, many of whom have since purchased rural property far inland. One claims to throw up whenever he sees a seascape. “It was exactly like the Titanic!” he tells his therapist and anyone else who will listen.

What, exactly, had happened? In a word: corrosion. When I initially cranked up, everything was fine until the clink. This sound was the flange connection between my manifold and exhaust system breaking three of its four corroded bolts. The breakage permitted the heavy pipe connection to gape open.

Once there was no exhaust pressure in my exhaust system, there was nothing to force the raw water out of my muffler. Hence, my entire exhaust system and large-diameter hoses filled with seawater.

After I shut off the engine the first time, some salt water flowed into my engine, not overboard. That’s why the engine hesitated while cranking the second time. But I didn’t realize the significance; I was too busy cracking dirty jokes in Mandarin.

Mistake No. 2 was failing to recheck my raw water visually. It wasn’t pumping overboard, and if I’d have checked it, I’d have never cast off. Again, my bad.

Before Carolyn cast off the mooring pennant, we were already in trouble. I was just too dumb to realize it. Pressurized salt water was spraying down the entire engine compartment. This caused numerous wires in my engine room to short out and begin melting their insulation. All this burning plastic, of course, produced massive toxic fumes.

Once we were back on the mooring, we aired out the boat, unloaded all the praying, happy-to-be-alive, we’ll-never-go-to-sea-again guests, and attempted to troubleshoot our problem.

Troubleshooting, of course, requires intelligence—why I thought I should be involved, I have no idea. I put Carolyn to port and Roma Orion to starboard, and cranked up the engine. They were supposed to tell me if they saw any new smoke or any tiny drips of water.

Roma was immediately drenched with salt water. From where? The raw-water injection riser after the manifold, where the raw water gets injected into the exhaust system to cool it.

At this point—idiot of limited intelligence that I am—I figured that I fully understood what had just happened. The hose clamp or hose had failed where the raw water goes into the injection point, and it had squirted under pressure, setting off a chain reaction.

Clever, me not.

At 3 a.m. the following day, I sat up in my bunk and said, “Oh, darn!” At first light, I unwrapped the vision-blocking fireproofing from the exhaust flanges that connect the manifold to the exhaust system. That’s when I saw the large, angled gap between the two. Without exhaust pressure in the system to evacuate the raw water, my engine exhaust system had filled completely with salt water. When I shut off the engine for the second time—thinking the emergency was over—the natural rocking and pitching of the vessel allowed salt water to get back-splashed into my cylinder head.

I now did what I always do in emergencies: I glued on a confident smile and asked myself, What the hell is going on?

The evil, ever-focused water molecules had finally had their day. I’d been too myopic to think through all the ramifications of the squirting water. Thus, corrosive salt water had been trapped in the cylinders for 18 long hours before I managed to get it out, and to fire up my no-longer-so-new engine.

How much damage did this salt water do? I don’t know. My engine currently starts fine. And runs OK. (Yes, I changed the oil a couple of times.) But, surely, having the engine flooded with salt water for almost a day didn’t help its compression, now or tomorrow.

And do I have another $20,000 laying around for a new engine? Nope! I could barely afford the new exhaust gasket and my extra-large serving of crow.

Why write such a depressing sea yarn? Because, as the T-shirts say, “Poop happens.” Despite a lifetime of guarding against salt water getting into any of the numerous engines that I’ve installed, my ever-plotting nemesis finally won a round.

Cap’n Fatty and Carolyn are currently in Langkawi, Malaysia, slapping paint on their bottom. (Did that come out right?)