The old saying “sooner is better than later” makes sense to most sailors. It’s especially true when it comes to safety training. The sooner you sign up for a safety-at-sea seminar, the better.

But the seminar is only Step 1. It’s the follow-up practice and vessel preparation that will ingrain those lessons and likely lead to the right response if an underway mishap occurs.

“Man overboard!” is a shout-out that no sailor wants to hear, and one which requires an immediate response. The skipper and best boathandler may be off watch, asleep in their bunks, and those on watch may have waited too long to tuck in a reef. Darkness, rough seas and a cross-swell can conspire, causing a crewmember to go over the side. The least-experienced sailor might be at the helm and see the incident unfold. At that moment, he or she is the most important person on the boat.

Preparing the crew for such an event is a skipper’s responsibility. A three-pronged approach works best.

The first step includes participation in a US Sailing Safety at Sea seminar, especially one that includes a hands-on in-water session on the second day.

Next comes the acquisition of equipment appropriate for the conditions and type of sailing.

Third are the practice sessions aboard your own boat, to implement everything learned at the seminar and get comfortable with the boat’s gear. The goal is to make a rescue as reflexive a response as possible.

Marine accident reports, which include feedback from sailors after overboard incidents, often allude to deer-in-headlights hesitation. Apparently, the big challenge stems from having to switch from watchkeeping’s familiar routine to the unfamiliar challenge—the magnitude of which can also hinder the response.

Fortunately, crews who have practiced fare better. So do their shipmates who have gone over the side. With enough practice, not only will your crew-overboard recovery skills improve, but so will your ability to pick up a mooring under sail.

The golden rule, when it comes to recoveries, is staying as close to the victim as possible. The quick-stop maneuver is meant to maintain that proximity, but the hasty tack into a heave-to position can be troublesome, especially if a boat is deep-reaching with large headsails or a spinnaker set. There’s also a jibe to handle as the vessel makes a circular- or ellipse-shaped maneuver and approaches the victim on a close reach.

An alternative maneuver—reach away, tack and reach back—eliminates the abrupt tack and jibe inherent in the quick-stop. But the “sail away from the victim” portion of the maneuver should be minimized. It adds the potential of losing sight of the person in the water, especially at night.

An overly hasty return also spells trouble. Excess boatspeed can result in a flyby that leaves the victim flailing in the wake and that lessens the chance of a recovery.

The ideal final approach concludes when a decelerating close reach and turn up into the wind results in a knot or less of boatspeed just as you approach the victim.

There’s no one-size-fits-all rescue maneuver. Some techniques are better-suited to fully crewed racing sailboats, while others fit the needs of those cruising shorthanded. The biggest challenge is everything that must happen nearly simultaneously. In addition to maneuvering the vessel, someone must shout: “Man overboard!” Others must deploy the MOB buoy and flotation, mark the position on the GPS, roust the off watch, keep the victim in sight, trim and douse sails, and steer the boat back to the victim. This can be tough, especially for the doublehander who suddenly assumes singlehander status. It’s why streamlining the recovery process makes a lot of sense.

I prefer a hybrid recovery for shorthanding situations. The process begins by stopping the boat via a tack into a heave-to position. With the victim in sight, mark the location electronically and deploy the MOB device. This ensures reference positions, just in case you lose sight of the victim.

Next, start the engine (leave it in neutral), furl the headsail, centerline the main, and motor a circular course similar to the quick-stop. Deploy the Lifesling and be sure the victim is to weather before rounding up. Tow the Lifesling line so that it intersects with the victim.

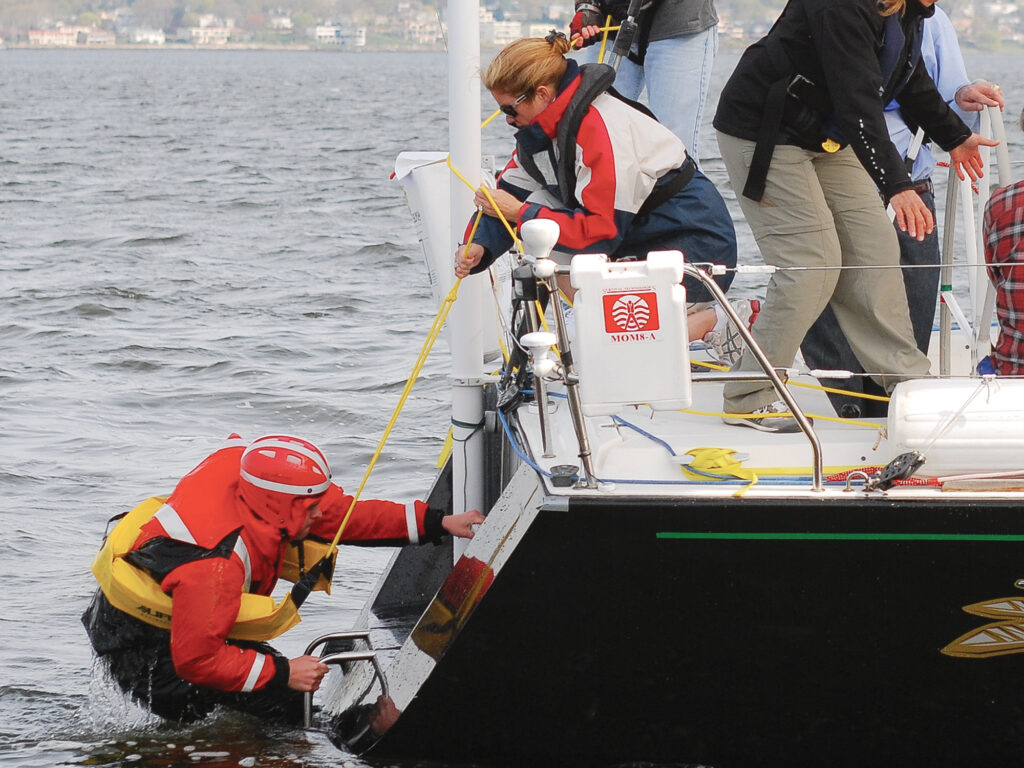

Before the horseshoe reaches the person in the water, the boatspeed should be near zero, with the engine in neutral. Once the Lifesling is secure around the victim, shut down the engine, make sure the boom is on centerline, and hand-haul the victim toward the boat.

Once the person is alongside, explain reboarding via a halyard hoist, stern platform or boarding ladder. When a swim platform at the stern is the choice, care must be taken, especially in heavy seas, to avoid the pitching stern’s downward plunges.

M.O.B. Must-Haves

Three of the most useful pieces of MOB recovery equipment, especially for shorthanded cruising sailors, are the Man Overboard Module, the Lifesling and an Ocean Signal rescueMe personal locator beacon.

The MOM is a quick-to-deploy inflatable pylon with a light that’s elevated 6 feet above the water. It’s attached to an inflatable, underarm lifting sling/flotation aid and has a ballasted 16-inch drogue. It comes in two sizes: 8-A and a smaller 8-S. The compact rail-mounted design is another big plus.

The Lifesling2 is a towable floating collar attached to a floating polypropylene line that the victim can grasp. This tool connects the victim and the vessel. The Lifesling2 also serves as a lifting harness during the final haul aboard to conclude a rescue.

Ocean Signal’s rescueMe MOB1 provides a digital link between a person in the water and all AIS units within range. It can also alert the person’s vessel via a digital selective calling alarm link. There’s a built-in strobe, and the unit can be set up with a PFD to activate automatically upon inflation of the life jacket, or it can be tucked into a foul-weather-jacket pocket and operated manually.