Back when tech-savvy kids could easily program a VCR clock while their parents were stymied by the blinking 12:00 display, sailors also slipped into a digital divide that remains today.

Shelving the lead line because the electronic depth sounder is a better tool upset no one. The progression of improving navigation electronics from radio direction finder to loran, and then satellite navigation was welcome. These tools gave us fast and accurate positions that we plotted on paper charts with a parallel ruler and dividers. If the magic box failed, we could revert to how we navigated before.

The slip really came when GPS and chart plotters became common. Press the “on” button and watch the screen light up, handshake with distant satellites, compute a position, and then plot it on an electronic chart. Each generation of new electronics became easier to use. Paper charts got musty, crammed into a locker.

But behind this apparent digital simplicity is complexity. There are circuit boards, processors, diodes, LEDs, network wiring standards, voltage drops, and a multitude of thin wires directing electrons to perform magic.

And when the magic box stops working, all kinds of challenges can result.

Trials and Tribulations

On approach to another beautiful, unpronounceable Maldivian atoll, we came in second place racing a nasty squall to the anchorage. We waited in the coral-studded lagoon with more maneuvering room for when the gust wall hit. Moments later, the air turned frothy white just about the same time our chart plotter displayed this message: GPS device not found.

“Not good,” I said, blinking rapidly, hoping that somehow my eyes would fix the empty display.

Our latitude, longitude, boatspeed, course and boat icon were all missing. The wind from the upper atmosphere was chilled, but I was sweating and tense. The magic-box fail felt, well, consequential.

In 45 knots of wind, a sailboat without sails up moves surprisingly fast. I was coming up empty on how to troubleshoot the GPS when a blinking sign in my brain reminded me to hold station. Point into the wind, and try to stay in this deepwater spot.

Without visual references, maintaining the correct rpm was a guess. I then realized that all the other electronics were working normally. On a whim, I dashed below, passing the helm to my wife, Behan. I disconnected the GPS antenna drop cable from the NMEA 2000 network, paused for two long seconds, and plugged it back in.

“It’s back!” were the sweetest words my wife could say in that moment.

After a minute of acquiring satellites, the boat icon appeared, and we remained clear of the reefs. The tense situation faded to just another squall waiting-for-the-rain phase, followed by calm so that we could aim for the anchorage again.

The Big Question

Paper-chart aficionados vigorously nod their heads when asked if we all rely too much on electronics. But paper-chart navigation offshore is still a complicated solution requiring a GPS (let’s be real: no cruiser relies on a sextant today) position to plot. We had spare GPS units, but not at the ready. Our glitch fix was to add a tablet with built-in GPS and chart-plotting software for redundancy.

Regardless, the digital divide is not in the tiresome debate between tradition and tech. Rather, it is owning the electronics so that they don’t own you when inevitable failures occur.

While in Cape Town, South Africa, our refrigerator stopped. It was as dead as an outboard drawing from a tankful of water. The breaker was on and the compressor wasn’t, so I checked voltage at the device. It was fine. I was stumped except to assume that the compressor motor had expired.

We found a marine fridge tech who figured out, in about two minutes, that the electronic controller had died. The what? I hadn’t really been aware of this magic box, that it could fail and be easily replaced. Lesson learned.

What electronics do you have on board? It could be more than you realize. Beyond navigation systems, electronics are commonly alternator and solar-charge controllers; monitors for batteries, tanks and engines; inverters and transformers; communication devices; computers; controllers that manage watermakers, refrigeration, outboard- and diesel-engine fuel systems; medical devices such as a defibrillator and blood-pressure monitors; EPIRBs and other safety gear; photography gear, drones, water toys, galley appliances, and a collection of little batteries charged with an electronic controller, preventing overcharge.

Ask yourself how inconvenient life would be if any or all of the above failed. Can you live without it, or should you have a spare? Is it field-repairable—by you and your anchorage buddies?

A coaching client of ours recently messaged to say that they couldn’t cross over to the Bahamas as planned because their autopilot was acting up. It drifted off course and gave incorrect headings.

I had them check around the autopilot’s electronic compass for tools, canned food, and other ferrous metals that might be creating electromagnetic interference. Tucked next to the compass was a work light with powerful neodymium magnets in the base. They didn’t realize that was a no-no, but they do now, and they were underway soon after.

The Art of Troubleshooting

Faulty electronics can be unrepairable, like our fridge controller. In Indonesia, we had an indirect lightning strike that fried our radar screen. But often, electronic glitches are field-repairable.

A must-have tool for the modern cruiser is a multimeter. It’s used to measure voltage and continuity, indicating if a circuit is open (no electrical flow) or closed. A DC clamp meter is also helpful. It’s much like a multimeter, but it measures current (amps) without having to touch the wire conductor. Another relatively new tool is a thermal imaging camera. As a smartphone attachment, these cost around $200 and easily show electrical hotspots.

Troubleshooting involves handling wires and connections, mostly of low-voltage DC electrical devices. This doesn’t pose an electrocution risk, but faulty components can become hot enough to cause burns. AC circuits do post electrocution risk. Always use extra caution when working around them.

When a device doesn’t turn on, or it turns on but has intermittent problems, start by questioning the power source. Is the power cord plugged in all the way, or does it have a loose connection? Is the circuit protection, breaker or fuse open?

The next step is using a multimeter to measure the voltage at the device. Does this show no voltage, open circuit, good voltage about the same as the house batteries, or something in between? Voltage more than 10 percent below the power source (batteries) indicates a physical wiring issue.

When the symptoms of a faulty device are intermittent, the root cause is almost always a loose, corroded or damaged connection or wire. An energized circuit with damage usually gets hot because of the resistance in electrical flow. A hotspot like that will show nicely on a thermal camera. This is especially useful because connection problems are often hidden under shrink tubing, buried in a wire bundle or inside a multiwire connector.

If the electricity reaching the device is good and the device still isn’t functioning right, check the settings for error codes and firmware updates. Many electronic devices have controlling software that can become outdated or corrupted. Last year, I found a calibration setting bug in our ultrasonic wind transducer. Tech support had a firmware update, but uploading it to the device failed. Customer support promptly sent out a replacement unit. Some devices don’t have easy updating procedures, but keeping the firmware current can eliminate problems down the road.

A final troubleshooting technique is to change the variables. If the device is on a network, then replace the network cables, network connectors and adapters. Try temporarily moving the device to a different place on the network or replacing it with a device known to work correctly. If a VHF radio has poor range and you don’t have a VSWR meter to test it, then connect a spare or emergency antenna to the radio and test again. If range improves, the problem is the coax cable, connections or antenna.

Success Is an Option

Magic boxes do fail. Cruising on our Stevens 47, Totem, since 2008 with a moderate level of electronic devices, our failures were mostly repairable, sometimes preventable and occasionally, albeit temporarily, a total loss. Provisioning to be remote for nine months during our recent North Pacific crossing required creative storage locations. I found the perfect place in which to stash box wine, but I didn’t recall placing an NMEA 2000 backbone cable connection there 17 years prior. The newly replaced ultrasonic wind transducer stopped working some months later. Tracing the cable led me to the vino stash, one bag leaking, a smell like a sommelier’s laundry hamper, and one rotten cable connection.

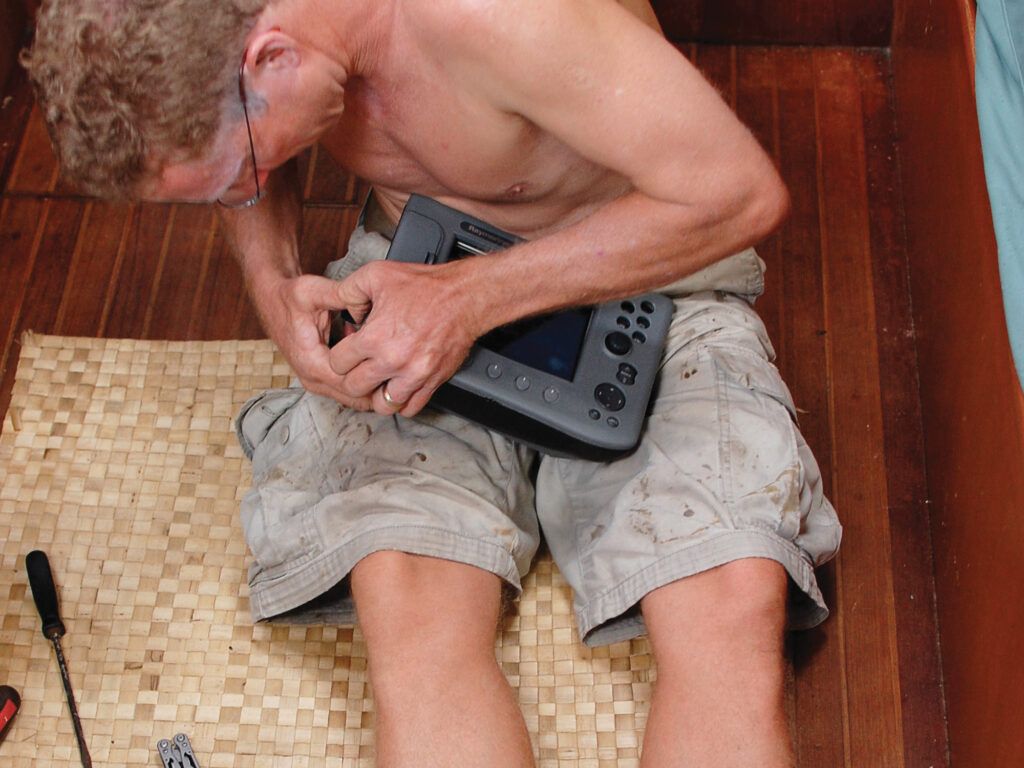

I thought it was a fixable problem as I cut off the cable ends, peeled back the covering insulation, spliced five thin wires, wrapped it in electrical tape, and secured it away from the ship’s stores. The wind instrument blinked to life.

A challenge of provisioning for so long is that it’s easy to lose track of where everything is. On that day, I had the wine wired, and it was about blinking time to get a bag of it chilling.

Starter kit for electronics troubleshooting

- Thermal imaging camera (smartphone attachment type)

- Multimeter (inexpensive end of the range is fine)

- DC clamp meter (for measuring amps by clamping around the wire)

- Wire cutter, stripper, crimper

- Soldering iron and solder

- AC receptacle tester

- VSWR meter