Bilbray Family

Parents Brian and Karen Bilbray of San Diego raised their five children around boats at the Coronado Yacht Club. When they decided to sail their 40-year-old Piver Lodestar, Barbarian, down to the Panama Canal and up the U.S. East Coast, they knew they’d have to “commuter cruise” between the boat and their jobs on both coasts. Their two youngest kids, Patrick, who was 22 at the time, and Briana, 20, crewed on long passages and boat-sat when Mom and Dad flew home.

On Christmas Day 2008, the Bilbrays departed from El Salvador’s Barillas Marina and motorsailed across the Golfo de Papagayo en route to Puntarenas, Costa Rica. At about 2200 hours, Brian, Karen and Patrick were asleep below when a papagayo, the region’s violent northerly wind, sprang out of nowhere.

“Briana was on watch,” Brian said. “She’d been clipped in on the foredeck watching porpoises cavort in the dark waters and had just returned to the cockpit when it happened.”

| |On the night of the dismasting, Brian and Patrick work to secure stays and mast on deck.|

Everyone heard one tremendously loud crack, then two more. First, one stay of their three-spreader rig parted. In the gale-tossed seas, the mast folded in half, and the entire rig collapsed astern to starboard, where Briana had been sitting a moment before.

A Family’s Self-Rescue

“Patrick jumped up and instinctively threw the throttle into neutral, accompanied by some strong expletives,” said Brian. “His quick action kept the prop from getting fouled by any lines.”

Struggling in the moonless dark, they lifted the mast pieces onto the cabin roof. Karen and Briana dragged the tangled lines, wires and spreaders back aboard, while Brian and Patrick secured them on deck and got Barbarian‘s trusty Yanmar auxiliary back in gear. When daylight arrived, they motored into the nearest shelter, Bahía Santa Elena, a well-protected bay within the uninhabited Santa Rosa National Park, on Costa Rica’s northern border.

Fortunately, no one had been injured, and the Bilbray family pulled together during the emergency. They never flipped on the EPIRB or tried calling for help, and they didn’t succumb to panic. “We just did what needed to be done,” Brian said.

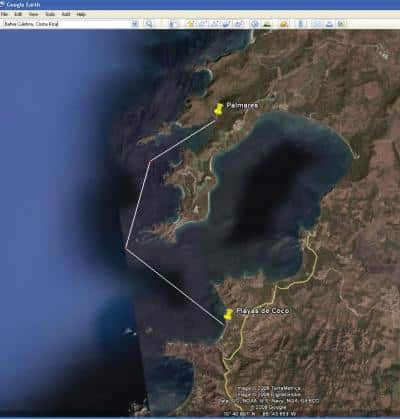

| |Brian used Google Earth when looking for a spot to effect repairs.|

They beached the trimaran for a thorough inspection, then spent a week making simple repairs. Bahía Santa Elena is so isolated that they didn’t see another soul. After the papagayo subsided, they motored back out into the Pacific. Puntarenas harbor was 175 nautical miles down the coast, which was too far to attempt. Their best chance was Bahía Culebra, 40 nautical miles south, with its 22 small but sheltered jungle anchorages. Barbarian came to anchor in Bahía Coco, located in the southwestern part of the larger Bahía Culebra; the boat lay off Coco’s primary village, Playas del Coco, population 200.

Matching the Mast

Piver Lodestars have been around a long time, but what were the odds of finding the perfect 48-foot replacement mast from an identical Lodestar in this remote Costa Rican outpost?

The Bilbray family lucked out. “Roy Bragg of Papagayo Marine found the mast for us,” said Brian.

It cost the equivalent of $20 to hire a truck to haul it out to the beach. Playas del Coco had no dock, so the Bilbrays anchored Barbarian in chest-deep water off a hard-sand beach along the only access road. A tourist walking by made the mistake of asking “Do you need any help?

| |Armed with a machete, Brian climbs a tree overhanging the water to secure a hoisting block.|

Brian, Patrick and their new best friend tied PFDs to the mast (just in case), hefted it onto their shoulders, then half-walked, half-swam the mast out to Barbarian. Quickly learning lessons in leverage, they hauled the mast up onto the cleared deck of an ama. That alone was a huge accomplishment. With some new wire and fittings purchased in town and their salvaged shrouds and spreaders, the Bilbrays pieced their whole standing rig back together on deck.

Over the next few weeks, Patrick stayed aboard Barbarian while Brian, Karen and Briana shuttled back and forth to stateside jobs.

The Jungle Hoist

| |Patrick works to make sure Barbarian is tied securely in place against the bank|

The Bilbrays’ stickiest quandary was how to raise the new mast without a dock or crane in this remote area. (Marina Papagayo has since opened in the region.) In search of a solution, Patrick took to his surfboard to scout the 20 nautical miles of the Papagayo peninsula and Bahía Culebra’s jungle shoreline. In Spanish, culebra means snake; caution was imperative. Patrick was searching for an ideal juxtaposition of shallow water below just the right height of overhanging tree limbs. On the north side of the peninsula, he found what he was looking for: the sandy, tidal mouth of a tiny seasonal river at the back of a narrow, steep-walled ravine clad in a jungle canopy.

When he was back in the United States, Brian used satellite imagery on GoogleEarth to gain a bird’s-eye view of the Bahía Culebra region. When he returned to Costa Rica, he excitedly shared with Patrick the spot he’d discovered from his outer-space vantage point. Father and son had pinned their hopes on exactly the same jungle location.

They anchored Barbarian as far as possible up the tidal stream. While Patrick secured the boat to hold steady amid the mangroves, Brian hacked his way along shore with a machete to reach the overhanging tree that Patrick had found.

Carrying a big block and messenger line on his back, Brian climbed the tree trunk, secured the top block as high as possible, then rove a lower block and tackle lines to the top of the mast lying on Barbarian‘s deck. Getting the new mast foot secured into the old mast step atop the cabin entailed more muscle and sweat.

| |As they begin to lift the mast, they discover two things: The blocks are set too low to complete the job with a rising tide, and the tree they’ve chosen is swarming with killer bees.|

“Soon Patrick and I were raising the head of this 48-foot mast a few feet at a time,” said Brian. “By afternoon, we had her halfway up at a 45-degree angle. But the incoming tide raised us so much that the blocks were now too low to lift the mast any farther.” They realized that they’d have to chop more branches off the tree to secure the block a few feet higher up.

About this time, an excursion panga full of tourists stopped to hail the exhausted, bare-chested gringos wading in the mangroves. Seeing the hull so deep in the jungle, the panga driver feared that the sailboat had wrecked. Although relieved to see that the sailors were OK, he warned them that the reason he brings tourists way out to Bahía Palmares is because they’re sure to spot crocodiles.

But the coup de grâce was delivered when the panguero, suddenly wide-eyed, pointed up at their hoisting tree. A writhing swarm of bees had settled a foot above the top block. The panguero called them “bees that kill.”

“Patrick is allergic to bee stings,” said Brian.

Local Knowledge Helps

| |Waiting until nightfall gives them the tide they need to complete the job, and the ability to reset their blocks while the bees sleep.|

Ingenuity and local knowledge proved to be the sharpest tools in the box. Seeing that the gringos still had to move their block even closer to the bee swarm, the panguero asked them if they could postpone the tree climb until after dark and if they could get the whole job done before dawn. Because, he explained, the “bees that kill” go to sleep at night.

The panguero wished them luck and departed. When night engulfed the jungle, sure enough, the bees went sufficiently dormant for Brian to inch back up the hoist tree. In the dark, he gently sawed off more branches, untied the line securing the top block to the tree, scooted up to within an inch of the bee mass, and resecured the top block.

“I kept one eye on the bees and the other on the boat,” Brian said. His plan was that if the killer bees awoke, he might not break his neck in a fall to the deck if he jumped into the snake- and crocodile-filled stream instead.

Getting the mast top elevated from horizontal to 45 degrees had been easy compared with the task of raising it to 90 degrees. As the clock ticked, the tide dropped and forced them to stop for a midnight nap. By 0230, the boat again floated, so they continued hauling on the block and tackle, keeping the hull correctly positioned in the pitch-dark mangroves.

Patrick finally was able to get the forestay wire attached on the bow. They then quickly hauled the new mast erect with the topping lift and secured it with the shrouds and backstay. Patrick was so relieved that he insisted on rowing Barbarian out of the creek by himself against the incoming tide. As dawn broke, Barbarian had so many lines still dangling from her new rigging that Patrick thought she looked like an ancient square-rigger.

Capt. Pat Rains, with her husband, Capt. John E. Rains, delivers yachts worldwide. Pat is the author of the nautical guidebooks Cruising Ports: the Central American Route