La Cruz, Mexico

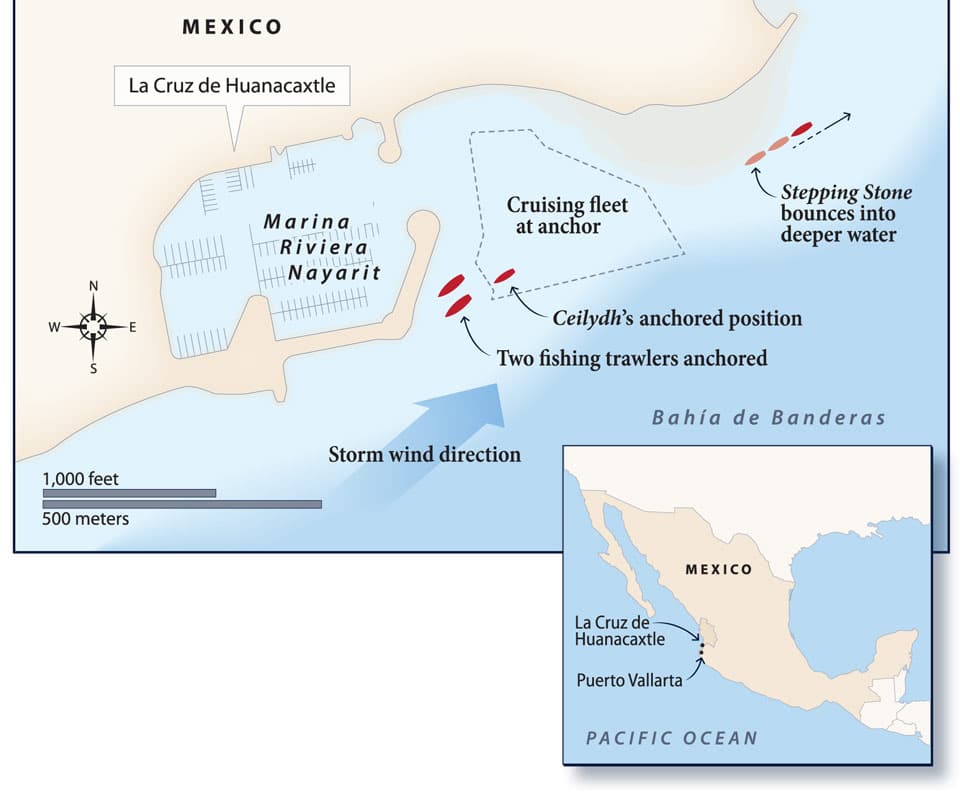

Bad weather is something we’re prepared for—at sea. But when the passage is over and we’ve dropped the hook, hurricane-force winds and 6-foot seas are the last things we expect. But we realize that extreme weather can happen just about anywhere. We experienced this firsthand when winds in excess of 80 knots ripped through Bahía de Banderas, on Mexico’s mainland near Puerto Vallarta, toppling trees, blowing windows out of high rises, and cutting power to towns around the bay. Over half of the 60 or so boats anchored in La Cruz de Huanacaxtle, in the northern part of the bay, dragged or lost their anchors, and dozens more ended up with shredded sails or impact damage. Two boats went aground.

We’d pulled into La Cruz in the afternoon of February 3, 2010, having just completed a four-day, 500-mile light-wind passage from Bahía Magdelena, on the west coast of the Baja peninsula. After taking a pass through the packed anchorage, we chose a spot on the seaward edge of the fleet. In a light offshore breeze, we set our anchor with 150 feet of chain and 30 feet of rope in 33 feet of water.

It was raining and a swell was running, but my husband, Evan Gatehouse, our daughter, Maia, and I headed to town to enjoy an early supper. When we got back to the boat, we noticed a polypropylene fishing line wrapped around our propeller. After failing to free it, we decided the 1/4-inch line would be easier to remove in the morning.

Around 2130, our digital barograph’s weather alarm went off, signaling a rapid drop in barometric pressure; it eventually dropped 7 millibars over 2 hours. By the time the big swell arrived, it was clear that something odd was going on, and we decided to pull our dinghy up into its davits.

Thirty minutes later, the storm hit at near full force, spinning Ceilydh, our Wood’s Meander 40-foot catamaran, 180 degrees and placing her at the head of the fleet, with a lee shore astern. The massive noise of the wind drowned out the thunder, but bolts lit up the sky all around us. While Evan monitored things outside, I kept an eye on the GPS and turned the radio up to full volume. It was clear that things were going very wrong. Anxious disembodied voices on the VHF wavered in and out. A voice reporting a dragging boat faded into other frantic voices: “Close your through-hulls!” and “Mayday!” and “It’s blowing 77! Now 82!”

| |The author and crew of Ceilydh, a 40-foot cat, fared well in the storm.|

Our anchor held, but the two 100-foot steel fishing boats immediately upwind were dragging toward us—and the rest of the fleet. I called a warning over the VHF while Evan turned on the engine. But because of the line around the prop and the force of the wind and seas, we weren’t sure it would help. We made a plan to slip our anchor and sail out under staysail if we couldn’t avoid the fishing boats. I got Maia into her life jacket, and I mentally prepared to lose Ceilydh.

The fishing boats dragged past, eerily close, one on each side of us while their crews struggled for control in the driving winds, pelting rain, and turbulent seas. They didn’t hit anyone else because, unknown to us, all the boats around us had dragged away.

Ceilydh came through the blow relatively unscathed—a situation that may have been due more to luck than skill. Our bow roller was damaged, requiring replacing, and our anchor line partially chafed through, but that was the extent of our damage. But we were curious to learn how the other boats had fared, wondering if we really had just been lucky or if there were clear lessons to be learned. So several days later, we invited the crews of five other vessels to share their experiences and tell us what they learned.

**_

Vessel:** m/v _OuttaHere, a Custom Trawler 60

Ground tackle: 121-pound Rocna with 250 feet of chain

John and Liz O’Cull first considered the approaching weather when the big fishing boats came into the harbor. “We’d been in La Cruz awhile, and we’d never seen them come into the anchorage before,” Liz said. She starting paying attention when “there was a big swell, and the wind—it just seemed different.” The subtle changes didn’t prepare the O’Culls for what came next. “The wind hit at 45 knots, then kept rising at a consistent rate. I could count off the numbers—46, 48, 50. It finally hit 85,” Liz said.

Located at the back of the fleet, OuttaHere was holding, but boats were dragging toward her. “In the lightning flashes, we could see them fly by,” John said. “Sailboats were in full knockdown position, with masts kissing the water.” His fear was that one would get tangled up in their still-deployed flopper-stoppers or snag their anchor.

“One boat did come dangerously close, but it missed colliding with us when the next wave picked her up and carried her away. We lost some canvas covers, but other than that, OuttaHere did fine,” John said. But the two cruisers were quick to point out that their experience was the exception. “We tend to anchor as far from everyone else as we can, so we were on the outer edge of the action,” John said.

Vessel: s/v Tynamara, a Spencer 53

Ground tackle: an 88-pound Delta with 300 feet of 3/8-inch high-tensile chain; 5/8-inch double braid secured the bitter end

For Jerry and Winn Brian’s Tynamara, the storm began with a hard gust. “The wind generator exploded while we were talking about putting the brake on,” Winn said. The next moment, a boat hit their starboard side and their two 1/2-inch anchor snubbers snapped with the force. Then the windlass let go, the anchor rode ran out, and the bitter end tore free. The couple got their kids up into the cockpit. “We didn’t have life jackets on yet, but the boat was getting trashed. Water was pouring in through open hatches and glass was breaking—we had to be in the cockpit,” said Winn.

With Tynamara heeled over at 45 degrees, Jerry was trying to get the prop to bite so he could steer the boat into the wind. “There wasn’t time to be afraid, but I thought we were going to hit the beach,” Winn said. Then the boat’s big engine started to move them forward. “That was when I knew we’d be OK,” Winn said. “Once we got moving, we got control.”

Disoriented by stinging spray and the lack of lights on shore, Jerry took Tynamara out through the anchorage and into the middle of Banderas bay to wait out the storm. “We didn’t even have the radio on,” Winn said. “We had no idea what was happening in the anchorage.”

**

Vessel**: s/v Prism, a 33-foot Hans Christian

Ground Tackle: a 35-pound CQR with an all-chain rode

In the anchorage, the other boats continued to struggle. “The storm arrived as a wall of water,” Joanie Werner said. “We had no idea where the wind was coming from, and we couldn’t see to figure out which boat was where.” Part of the problem were the fierce seas: “They had no rhythm or predictability,” Joanie said. “It was like those storms you see in the movies, the ones that are so violent that they don’t seem real.”

Joanie and Leon, her husband, had their life jackets on but realized there was nothing they could do but hold on and be prepared to escape. “We had the depth sounder on so we’d know if we were dragging, and we had a compass course set for open water,” she said. “But we knew there was no way to add scope, and we doubted that we could even motor against the wind.”

The couple, who’ve been sailing for 35 years, said that time seemed to stop during the storm. “We knew we’d set the heck out of the anchor, but the storm just kept going and going,” Joanie said.

Vessel: s/v Star Dancer, an Outbound 44

Ground Tackle: a 66-pound Spade anchor with 200 feet of 5/16-inch high-tensile chain

On Star Dancer, it was the roar of the wind that woke Dave and Mary Ann Plumb. Turning on the VHF, they heard a Mayday—a boat was on the rocks. “Then we were hit,” Dave said. A large ketch crashed into Star Dancer’s bow with a force that the Plumbs thought was sure to hole her. The blow ripped their anchor free and set them hurtling downwind.

“We grabbed our safety gear and headed outside,” Dave said. The Plumbs realized that they couldn’t hold position as they tried to make their way into the wind, so they started keeping an eye on the depth. Their effort to get to safety, Dave said, “was like the wrestling contest of my life.”

Dave followed the contour of the coast until Star Dancer was free of the anchorage. They checked for water from the collision; amazingly, the hull was intact. “Everything stayed strong,” Dave said.

**

Vessel**: s/v Stepping Stone, a Maple Leaf

Ground tackle: a 55-pound CQR with 250 feet of 3/8-inch chain

The Mayday heard throughout the anchorage was from Stepping Stone. Located in the center of the fleet, Elias and Sarah Anderson reported that they didn’t have enough scope out. “The anchorage was crowded, and we wanted to be near the dinghy dock,” Elias said. When the gust came, it knocked them over and spun Stepping Stone 180 degrees. “We went from one end of the rode to the other, and then just kept going,” he said.

“I instantly knew that we were dragging,” he said. “We were sliding sideways. I ran up to the bow to let out all my rode.” They caught for a moment, but then the shackle tethering the bitter end to the mast ripped free. Meanwhile, Sarah was trying to start the engine, a diesel with glow plugs that needed to heat up. “It was the longest 30 seconds of my life,” she said. “I watched us fly past six boats. I thought we were going to hit every time.”

The engine started, but with the boat knocked over, it was useless. “All I could do was get the centerboard up and wait to hit the beach,” Elias said. Sarah had their girls, Kimberly and Savona, in their life jackets and in the cockpit when the boat suddenly slammed into a rocky reef jutting out from the beach. “We were on our side,” Sarah said. “The mast was pointing at the beach. I could hear the boat grinding on the rocks. Water was coming over the coamings.” Elias turned the engine off and told his family that they’d done their best, but they were going to lose the boat. He had time to call the Mayday and secure things. “He even gave us a little pep talk,” said Sarah.

“Then a wave lifted us up and we were free,” Sarah said. “We turned the engine back on and couldn’t believe when the prop caught. We were motoring, on our side.” Elias thinks they must have caught a brief lull, “The wind sure hadn’t dropped yet,” he said. They made for open water, shocked by their luck but still not sure what was happening with the weather or when it might end.

After 45 minutes of sustained 75-knot winds, with gusts reported as high as 92 knots, the wind began to drop. After an hour, the wind was 35 knots and had clocked around to an offshore breeze. On the VHF, relieved chatter began replacing urgent radio calls. Boats that had broken free began limping through the confused seas, estimated at between 6 and 8 feet, and into nearby Marina Riviera Nayarit. There was a lot of damage to the fleet, but no boats were lost. Human injuries were confined to sprains, bumps, and bruises. The fleet consensus was that storm planning needs to come well before the wind hits. Leon Werner from Prism said it best: “If you didn’t do it when you anchored, you’re not going to be able to do it when it hits.”

Lessons Learned in La Cruz

• Buy the right anchor: Manufacturer guidelines typically suggest sizing an anchor according to boat length and for maneuvers in average conditions; they’re not envisioning a heavily loaded cruising boat anchoring in a wide range of situations. Err on the side of “Bigger is better,” then set the heck out of it.

• Use enough scope: More than a few sailors on boats in La Cruz admitted to using too little scope, the length of rode paid out based on a ratio of length from the seabed to the height of the bow.

This was something the cruisers all thought they could add once bad weather hit. The reality was that the boats that tried to let out scope were among those that lost their anchors.

• Secure the bitter end: More than a few boats lost their anchors because the bitter end wasn’t secure. After their snubbers chafed through or the windlass brake failed, the anchor rode ran out. The bitter end was either not attached at all or attached too weakly.

• Have a plan for recovering your anchor: Several anchors were lost in La Cruz, but only a handful were recovered. No one had time to buoy their anchors, but one boat had a 20-foot length of yellow polypro line secured to the bitter end. The yellow line floated below the surface and marked the end of the anchor line for searchers.

• Stay prepared: The boats that had just completed passages and still had gear stored away and their decks clear fared better than their less orderly neighbors. Boats with dishes and computers out ended up with cabins filled with broken glass.

• Watch the weather: The weather anomaly, which pushed a subtropical blast north to collide with a cold front that had strayed down from California, caused a near classic weather bomb. No one forecasted the storm, but the falling barometer and other atypical weather signs did provide clues.

• Keep the safety equipment handy: Easy to grab life jackets, flashlights, handheld VHFs, and ditch bags topped everyone’s lists as items that they should’ve had better organized and available. Having a snorkel and dive mask handy can also help with visibility in heavy spray.

• Establish a radio net: If you’re in a harbor with more than a few boats, assign one person the role of net control. In La Cruz, the radio chatter got in the way of Mayday calls and other information. No one, for example, ever followed up with Stepping Stone after the crew’s Mayday call.

• Have an escape plan: Once the lights on shore went out, most of the crews became disoriented. Having an escape route programmed into a GPS and knowing the compass course out to safe water saved at least two boats.

• Double-check your furling gear: Be sure you furl your sail with several wraps securing it, and tie the furling line so it won’t unwind in a blow. At least 30 sails were badly damaged because they were poorly furled.

• Label your stuff: It’s amazing what can blow away in 80 knots of wind. Jerry jugs, dinghies, oars, kayaks, surfboards, and paddles all littered the shoreline the

next day. Most carried no identification.

Diane Selkirk set sail from Vancouver, British Columbia, in September 2009. After a year in Mexico, she and her family continued on through the South Pacific to Australia—carefully watching the weather and avoiding storms whenever they could.