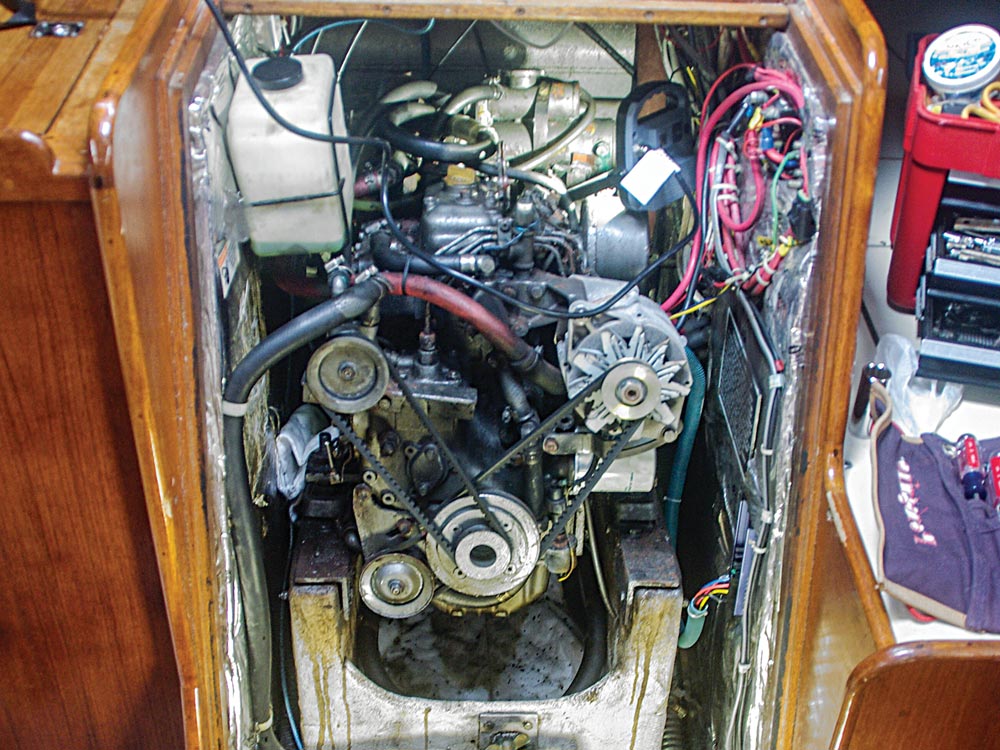

The 30 hp Yanmar 3HM30 diesel engine had given good service since my C&C 40 cruiser/racer, Peregrine, was built 36 years ago, and though it still fired up the instant the starter button was pressed, keeping it running had become a constant chore. Every time my wife and I went for a cruise, I had to waste precious time fixing the engine. I was craving a nice, low-maintenance alternative — especially given our plans to sail to the Caribbean one winter soon. After spending one more sunny summer afternoon while moored in Vineyard Haven, Martha’s Vineyard, attempting to fix the engine, I finally gave up and placed a call to Mike Muessel, owner of Oldport Marine in Newport, Rhode Island. I told him I was ready for that new engine we’d discussed at the Newport International Boat Show the previous summer. He told me to come on over because he just happened to have the engine I needed sitting in his office and he could have me sailing again before Labor Day weekend. A glorious night sail upwind in 20 knots of breeze got me home to Newport, and in the morning, Mike said he was ready for me. I sailed over, and just off his dock in the heart of town, I fired up the old Yanmar. Just as I tied up at the Oldport dock, the overheating alarm went off for the last time.

A good way to keep a diesel engine operating well is to run it under load on a regular basis. That never happened with my boat’s little engine. Like pretty much every sailboat auxiliary, it had been laid up for the winter, was often run slowly to conserve fuel on long passages, and spent many hours idling to charge batteries — about the worst way to operate a diesel engine. That it was running at all was a testament to the maintenance done by the previous owners and me, as well as the quality of the rather “agriculturally” marinized little Yanmar tractor engine to start with.

Deciding Factors

The Yanmar 3HM30 is a three-cylinder 30 hp diesel (at least, it developed 30 hp when it was new). Muessel and I had pegged Yanmar’s new 30 hp 3YM30AE as the best replacement. Like its ancestor, it is mechanically injected, meaning the timing of the spurt of fuel that the injector sprays into the top of the cylinder is mechanically controlled by the revolutions of the engine, but it emits far less exhaust gas and was expressly designed for marine use. Muessel and I had toyed with the idea of upgrading to Yanmar’s super-efficient new four-cylinder common-rail engine, the electronically fuel-injected 4JH45, which yields 45 hp for nearly the same fuel economy as the 3YM despite having even more in the way of emission controls. It would have fit in the engine compartment, but the fact that it is marginally bigger in an already tight space (and $3,000 more), and the fact that my C&C 40 hits hull speed under sail in very little breeze, made me opt for the less powerful cousin.

The decision being made, Muessel introduced me to the guys who would be doing the work: head mechanic “Diesel Mike” LeBlanc and Ethan Salsberry. They came down to the boat to assess the extent of the project and talk about timing of various work stages. Budget being a serious consideration for me, and knowing that I’m not entirely incapable on a boat, Muessel allowed me to do as much of the work myself as possible.

The next couple of days involved much wiggling into tight spots, removing hoses and wires, and repeated applications of PB Blaster — and occasionally heat — to free up rusty bolts. An 18-inch breaker bar for 1/2-inch sockets was invaluable for disconnecting the shaft coupler; there’s nothing like leverage for loosening rusted bolts!

Prep Time

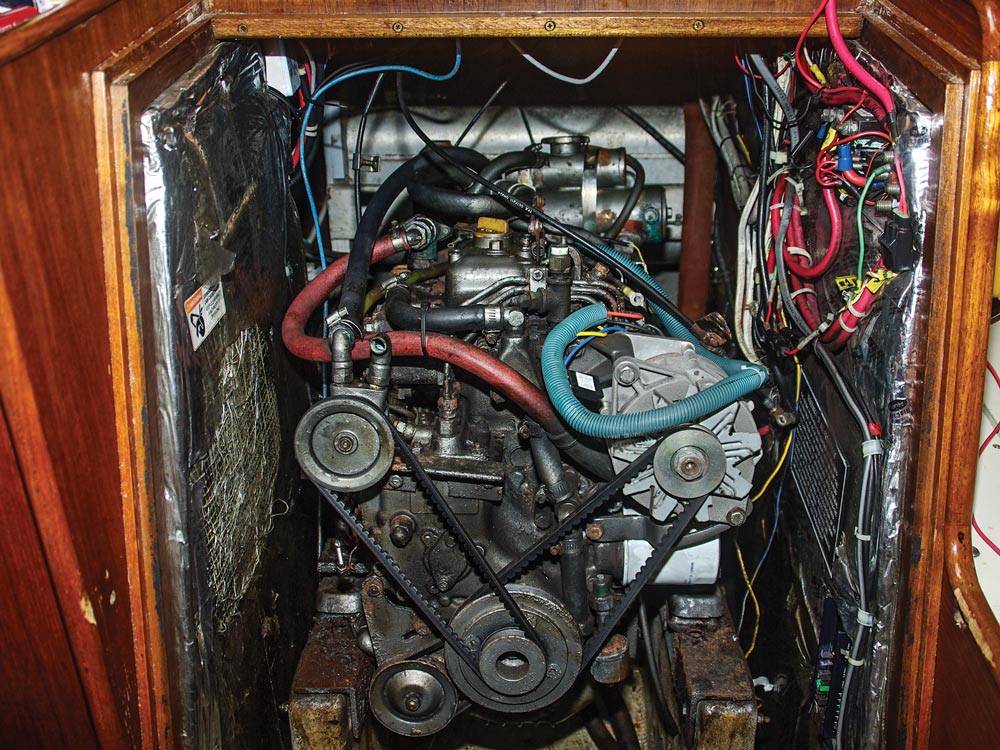

Many years ago, when I was starting out in the marine industry, my many mentors impressed on me the desirability of keeping engines and their surroundings clean. It makes maintenance much easier, and drips of this or that will show up immediately, allowing the skipper to get on top of problems while they’re still minor. It had been driving me nuts that I wasn’t able to keep the engine and its compartment sparkling on my own boat. That wasn’t my main reason for replacing the engine, but it was certainly a lurking factor in my decision.

Several rolls of paper towels, a couple of cans of degreaser, scrub brushes and many sheets of green Scotch-Brite pads later, the engine compartment was clean enough to eat off, though still stained and brown. I also found several lost wrenches and sockets.

While I had the space to work, I decided to replace the insulation on the side of the engine box near the fuel lines, lift pump and other parts from which wrenches and drivers had slipped in oily fingers, tearing the foil surface. Using the old piece as a template, I cut a new sheet of 2-inch-thick leaded Soundown foam insulation and installed it. At this time, I also removed the old Racor primary fuel filter and took it to my workshop, where I thoroughly cleaned, repainted and replaced all the old O-rings before reassembling and remounting it. I even soaked the bronze T-handle in Coca-Cola overnight to remove the corrosion, and then polished it just to make sure the whole thing looked new when it went back in.

The next project was one I’d been looking forward to since I bought the boat: painting the engine compartment with gloss-white Interlux Bilgekote, an excellent heavy-duty finish designed to stand up to the oil, water and detritus often found in bilges — not that my clean engine room would ever be subject to that filth again! A couple of days and two coats later, I had the immaculate engine compartment I craved. Now it was time to turn the project over to Ethan.

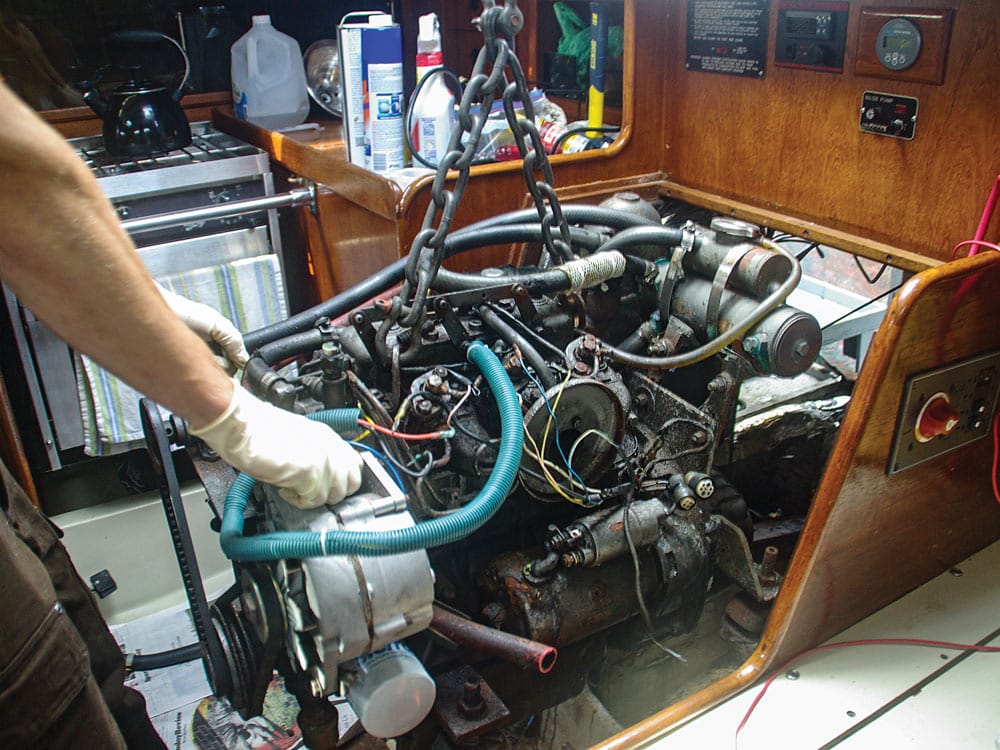

Relative to the coupler for the prop shaft, the mounting brackets on my new engine were a little higher than those on the old one. That meant that the engine supports on the boat would need to be cut down. This is a very precise operation at a skill level far above my pay grade. Ethan (“I don’t know how many re-powers I’ve done in the past seven years at Oldport — lots.”) measured the height of the prop shaft coupling — assuring me as he did that the shaft was nice and straight — and cut the supports to the precise height. Aluminum rails were bonded to the fiberglass and laminated-wood supports with epoxy and bolts. These replaced the old rusty steel rails I’d removed as part of the cleanup process.

As Ethan was taking care of his projects below, I started mounting the new control panel. As expected, the dimensions were different from the old one, so I cut a piece of StarBoard to cover the hole in the old location and then fit the new panel onto that and screwed and sealed it in place.

All Systems Go

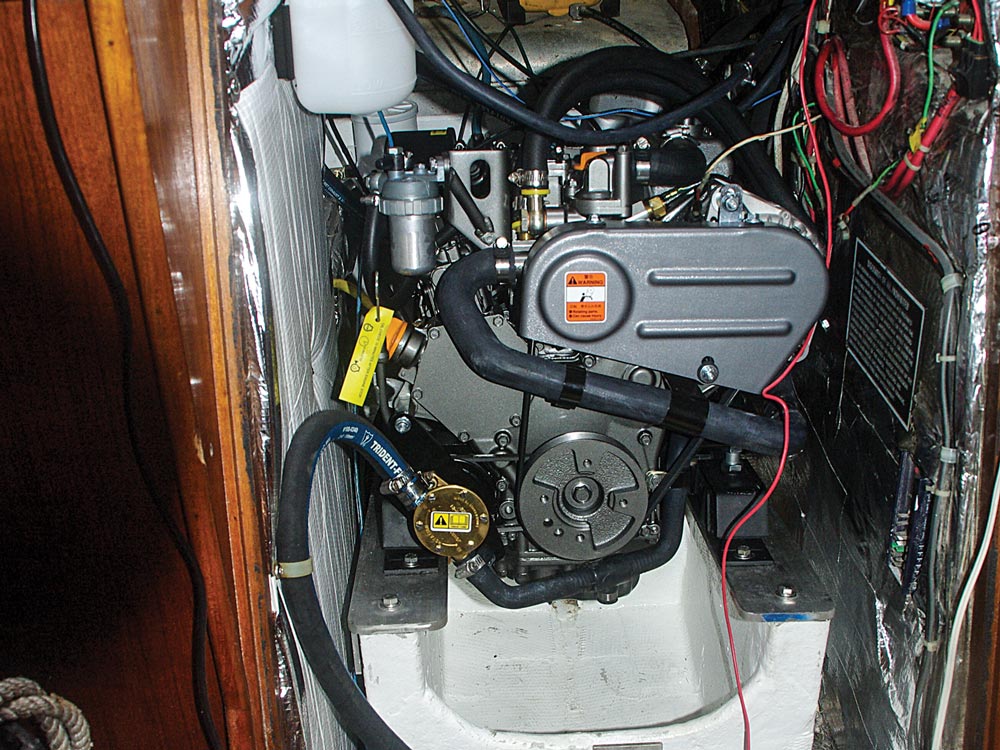

Just a week after arriving at the Oldport Marine dock, we were ready to install the new engine. Out came the chain-fall hoist again, and soon the new diesel was sitting in its new home. A few measurement checks later, Ethan and I pulled the engine out into the galley so he could drill and tap the holes for the mounts into the aluminum rails. Moving the engine back into place, Ethan bolted it down before moving aft to attach and align the propeller shaft, a process that, thanks to his expert preparation, took remarkably little time. The fun part came next: hooking everything up. I left all the electrical systems and the exhaust to Ethan while I got the fuel lines, raw-water hoses, water heater and assorted other hoses attached. One important change Ethan advocated was to raise and put an anti-siphon loop in the exhaust water line between the exhaust manifold and the mixing elbow. He felt that underway — especially while sailing — the top of the engine might be below the boat’s waterline, allowing seawater to back-siphon into the exhaust manifold, filling the cylinders and causing a hydrolock.

The engine had been shipped with no fluids, so we added engine and transmission oil and coolant. And then, while he watched below, Ethan gave me the go-ahead to push the button and start it up. With just a touch it fired up instantly, purring quietly beneath my feet! I took a video of the running engine — with sound — and emailed it to my wife, who somehow managed to contain her excitement, though I’m sure she was as enthused as I was.

The next step was a sea trial, with Ethan observing and adjusting. The 3YM30AE is designed to max out at 3,200 rpm. Underway in forward gear, I ran it up to full throttle, and it turned a little better than 3,500 rpm, which meant that there wasn’t as much load on the engine as it was designed for; in other words Peregrine was under-propped. At cruising rpm (75 percent of maximum throttle), we only made about 5.3 knots instead of the 6.5 it should cruise at, confirming that we needed either a bigger propeller or more pitch in the existing one. We had expected this because the old transmission had a 2.1-to-1-reduction gear ratio, meaning that for every revolution of the propeller, the engine had to turn 2.1 times. The new transmission has a 2.6-to-1 reduction. Fortunately, Peregrine has a racing heritage, which had included installation of a low-drag feathering Max-Prop from PYI in Seattle. PYI’s Fred Hutchison consulted his tables for that particular engine in a deep-keel C&C 40 and suggested that we adjust the prop to dial in an inch or two more pitch. Ethan advised that we start with just one more inch, pointing out that too little propeller pitch was better for the engine than overloading it with too much.

Chris Ringdahl, manager at Brewers Cove Haven boatyard, a few miles up Narragansett Bay, said yes indeed they had time to do a “short haul” to change the pitch on the prop while Peregrine sat in the travel-hoist slings, so off I went, reveling in my new quiet, smooth-running little engine.

After the increase in pitch, the engine turns up to 3,400 rpm — still too high — but cruising at 2,500 rpm I’m able to do a solid 6 knots in flat water, which is better than I had been able to eke out of my old engine.

As part of this winter’s maintenance I was planning to send the prop to PYI for refurbishment anyway, so while it’s there, they’ll dial in the extra inch before sending it back to me in the spring. A change I didn’t plan on, but should have expected, is that when I reverse, the boat pulls harder to port than it did with the finer pitch. I can easily adapt my maneuvers to the added prop walk.

Now that I have motored most of the way to Maine and back, racking up more than 50 hours on the new engine, I’m delighted to note that I’m going faster than I used to for the same fuel economy, burning just over half a gallon an hour. The only reason I’ve had to go into the engine box is to check fluids and give the engine its 50-hour oil change (though I have to admit that I sometimes open the lid while we’re underway just to watch and listen to it tick over). Both my wife and I appreciate the difference in the noise level and the huge reduction in vibration. I do, however, feel sort of guilty that I haven’t been in to visit my old engine in the back of the shop at Oldport Marine.

Andrew Burton has been a yacht delivery skipper for more than 30 years, logging more than 350,000 nautical miles on various boats. He and his wife will cruise from their home in Newport, Rhode Island, to the Canadian Maritimes and the Caribbean aboard their new (to them) Baltic 47, Masquerade