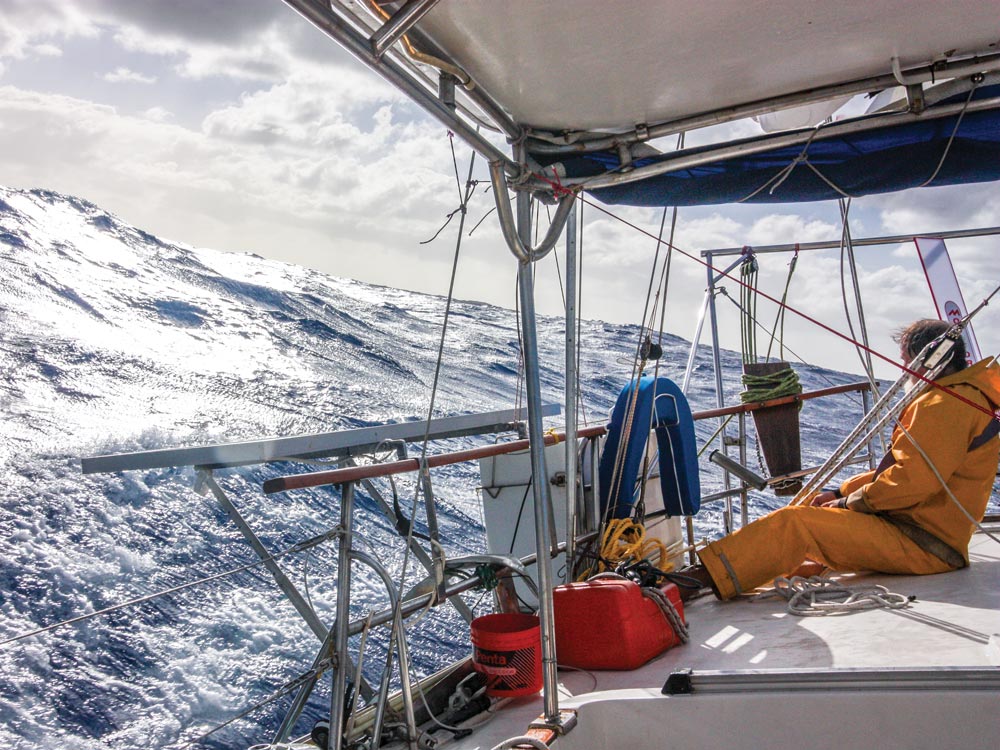

Coming out from under the lee of Tongatapu, Tonga, we were rail-down despite flying only our small trysail and tiny storm staysail. The wind was easterly. It was blowing a steady Force 7, gusting to gale force. The resulting seas were huge. Our boat speed was 8 knots on the crests — slightly less as we labored in the troughs. We were attempting to punch through the high-velocity wind wall of a BFH (big fat high) that had established itself between us and our destination: New Zealand.

Ganesh, our rugged but weary 43-foot Wauquiez Amphitrite ketch, was beam-reaching amid mountainous seas, not the most comfortable point of sail when Mother Ocean is in a boisterous mood. Rolling is a real possibility while beam-on.

Occasionally, a boarding breaking wave would ring us like a bell. We had a thousand miles to go to reach Opua, with air and sea temperatures plunging the whole way. Wise?

“Damn it,” said my wife, Carolyn, irritably. “I thought you said it would be fresh, not frightening.”

It was a tricky weather window. This passage is usually the most difficult of any circumnavigation. Speed was of the essence. We needed to be anchor-down in the Land of the Long White Cloud before an intense low-pressure system rolled up from the Tasman Sea. There are lots of reasons for a sailor to loathe a high-pressure system in the Southern Hemisphere, but a fair wind is a fair wind, even if there’s too much of it.

Sure, Carolyn and I had repeatedly discussed this emerging window, as a blockage in faraway Cape Horn caused the BFH to stall out. But the final call to leave safe harbor had ultimately been mine, and perhaps I’d called it wrong. Hell, we’d only been offshore for a few minutes and I was already thinking of running off before it or heaving-to — hardly a positive sign. And the sleepy inner harbor of lovely Nukualofa, which we’d just left, had been flat as a pancake. Tonga is a very romantic place. We were in no rush. Happy hour at Big Mama’s is always fun. So, how stupid was I?

Ganesh heeled sharply to starboard, buried its bow up to its windlass and attempted to round up. Our trusty Monitor windvane muscled the boat back on course. Wet, straining halyards tat-tat-tatted against the mast. I glanced at the wind speed: a sustained 37-knot gust. Carolyn and I locked eyes. I could tell she was forcing herself not to ask, “Why do you call this pleasure boating, Fatty?”

Our lee rail dipped into solid green water, and a frothing deck sweeper boarded us. Our cockpit filled. A hardcover book that had stayed wedged in place across the entire Indian Ocean flung itself across the main cabin with pages splayed. Something plastic fell and rolled. Our Dyneema staysail sheet hummed like a taut bowstring.

“Oh, it’s a sailor’s life for me,” I sang without conviction. Carolyn glared at me again, as if to say, “Misery loves company.” I stood with cold seawater swirling up to my knees, asking myself how old I’d have to become before I’d know better.

I considered turning back.

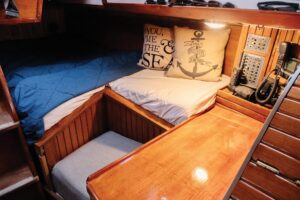

“I hate this,” Carolyn said from the companionway, eyeing her pilot berth below. “This is silly, sailing into 30-plus-knots when we could be in safe harbor.”

I remained quiet. She’d be back to her jolly old self soon. Why agree on the obvious: that Ganesh had an idiot for a skipper?

“Nowadays, only a supercomputer can figure what our ancestors used to know by glancing at the sky.”

Traditionally, I’ve not been overly fond of weather routers. It strikes me as somehow dishonest to consult some electro-dirt-dweller who sits ashore surrounded by broad-banded computer screens; it’s as if I’m unfairly conspiring against the wind gods. Did Joshua Slocum use a weather router or defer to PredictWind? Buoyweather? Windy.com?

Then why should I?

“Perhaps because you want to stay married?” a feisty Carolyn would ask.

Well, there’s that.

Whenever I launch into my “Embrace the storm!” rant to a group of unsuspecting sailors, Carolyn rolls her eyes and twirls a finger at her graying temple to visually add her two cents. As far as she’s concerned, the only good storm is the one you ride out in a protected harbor.

She’s not alone in being weather-shy. More and more sailors are purchasing various professional weather products while circumnavigating and sailing offshore. “You’re talking through your hat,” I’ve been told more than once by a wealthy sailor with a satphone, a credit card, and an expensive custom forecast from some unseen weather nerd in Boston, Florida or South Africa.

It used to be that every Jack Tar was his own weatherman, but not anymore. Now you’re supposed to ignore your barometer falling into your bilge and wait for your remote weather guru to consult with NOAA to inform you thereof. Ditto dew on the decks, a halo around the moon, or the wind backing or veering. Nowadays, only a supercomputer can figure what our ancestors used to know by glancing at the sky.

If the above isn’t bad enough, I’ll admit that Down Under weather forecasting is more difficult. The highs and lows rotate backward from what we Northern Hemisphere sailors are accustomed to. Worse, not everything goes the opposite direction. The tropical trades on both sides of the equator still blow from east to west regardless of the Coriolis effect.

As a young, brash sailor, I focused solely on my boat prep and ignored long-range weather predictions. But as slivers of maturity intruded on my life, I began to realize that passage didn’t have to be a synonym for suffering. I developed a system of getting in sync with the weather before shoving off. We’d plan to sail in 72 hours’ worth of benign conditions at first, then stoically take whatever came next. After a half-century of offshore sailing, last month I asked myself how this was working out and came to the undesired conclusion: not too well.

We’ve done the trip down to New Zealand five times now. It would usually take us more than two weeks and two full gales to reach the Bay of Islands. Yuk!

Enter David Sapiane and Patricia Dallas of Gulf Harbour Radio (ZMH286). They are two wacky ex-sailors who washed ashore in New Zealand and have a sort of demented morning marine weather show on 8 megs SSB (ghradio.co.nz). She’s a Kiwi-born unfulfilled news presenter, and he’s a frustrated weatherman. Their program sounds as though it’s written by the ghost of Groucho Marx. Best of all, David proclaims, “We will never, ever charge for a weather forecast!” Even a struggling writer like myself can afford free.

So I listened for a couple of weeks, and was impressed by how David could convey complex global weather concepts so that even I could understand them. The whole trick of our upcoming passage was to ride a slow-moving high-pressure system down to Kiwiville — the only problem being, the higher the pressure, the higher the initial winds of the outer bands.

“Anything over 1030 millibars will have high winds in the Tongan area as it stalls, and often a full gale in a trough on its backside,” noted David.

The center of this particular BFH was 1038 millibars, and it was predicted to just sit out there for 10 days, blowing anyone into New Zealand who could survive the first two days of heavy air. Hence our current predicament.

RELATED: 7 Affordable Low-Bandwidth Satellite Systems For Offshore Sailing

Of course, since weather forecasting consists of dealing with both pattern (weather systems) and chaos (how they interact), it is as much art as science. Any modern sailor with the proper communications equipment can download GRIB files, but those are only a part of the picture, the raw data. This data needs to be interpreted. David is good at this. Damn good. And he has the advantage of having studied the same little watery patch of our planet for decades.

I decided to give his advice a try.

In order to do so, I had to pry Carolyn out of port, which is never easy. Carolyn loves with the open heart of a child, and was firmly embedded in her watery tribe. Each evening we’d have a different cruising couple over for dinner aboard Ganesh: Kyle and Maryann of Begonia, Rob and Carly of Yonder, Hank and Lisa of Harlequin, and Franco and Cath of Caramor. They were all part of our rainbow cruising community, a true movable feast.

The good news is that everywhere we sail, my wife loves dearly; the downside is that she never wants to leave her current Harbor of Eden. Over the past 49 years, I’ve learned I have to lure her away with the combined promise of fresh adventure and old friends.

“Won’t it be great to spend Thanksgiving on Kawau Island with Lin Pardey again?” I asked Carolyn. “And having Alvah and Diana Simon of Roger Henry aboard in Urquharts Bay will be a blast, right? Comforting Sequester’s Ted after Karen’s passing, and visiting Sharron and Brian at the Town Basin in Whangarei, it’s all good, no?”

My shipboard challenge was entirely different. Normally, we have days at sea to prepare for a gale, but this time we were going to experience 30-plus-knots and large seas just beyond the harbor mouth. We had to be ready or chaos would result and morale would plummet. I double- and triple-lashed the upside-down dinghy on the foredeck, stowed all jugs belowdecks, and inspected every inch of the rig with a magnifying glass. (Yes, I spotted a corroded mainsheet shackle in the nick of time!)

Fuel, check. Water, check. SSB, check. Jordan series drogue and Para-Tech sea anchor, check, check. Good luck charm, check. A non-Friday departure, check!

Finally, I cranked up our Perkins diesel and watched the oil pressure build.

“Are you sure?” Carolyn asked as she came on deck.

“I’m never sure,” I said. “That’s for dirt-dwellers who return to the same dreary place each evening. Uncertainty is the price of adventure. Life is risk. Anchor snubber off, please.”

Carolyn ambled forward, leaning into the wind and shaking her head ruefully.

So, how did the passage pan out? Thanks to David’s superb long-range offshore forecasting, nearly perfect. We suffered no damage and averaged twice our normal speed because we were never forced to heave-to or sail to windward. Hell, we never even tacked as we clicked off seven 150-plus-mile days in a row.

“Those shrouds on the starboard-side were dead weight,” I joked to Carolyn as we powered past the old whaling town of Russell on the way to Opua. “We didn’t need them a’tall!”

Ashore in New Zealand, Carolyn immediately immersed herself in a weeklong welcome-back party, courtesy of the local marine industry and a dozen cooperating bartenders. And as I write, we’re on a mooring in front of Lin Pardey’s island home and about to dinghy ashore for a traditional American Thanksgiving feast.

I smelled baked apple and cinnamon as I stood on our aft deck, yards away from her tidy dock. It felt good to be alive, even if I was wearing long thermal underwear and a wool watch cap.

“I love New Zealand,” a hungry Carolyn whispered to me as we hugged before climbing into the waiting dinghy.

“Even the bad parts?” I asked.

“Bad parts?” she asked, and smiled at me. “What’s a capful of wind between lovers?”

Cap’n Fatty and Carolyn are recovering from hosting their daughter, Roma, and granddaughters, Sokù and Tessa, for the holidays aboard Ganesh in New Zealand.