Sometimes life brings a moment that stands out from the rest. Time stands still for one brief, clear instant. You look up with astonishment and realize that the circumstances into which you’ve somehow been delivered are well beyond your wildest imaginings.

I had one such moment recently, in the unlikely location of Rongerik Atoll: a tiny, uninhabited slice of beach on the northeastern edge of the Marshall Islands archipelago. My partner, Liam, and I had sailed into Rongerik’s lagoon several weeks earlier. It was our last stop before making the jump from Micronesia back to North America. We had greatly enjoyed this quiet paradise, exploring the reefs, sharing the company of resident coconut crabs and seabirds, and looking for turtle tracks on the wide sand beach. Eventually, our weather window had arrived, and we’d dragged ourselves away from the easy island life to poke our noses back out into the wide, empty Pacific.

It was at this moment, as the protected calm of the lagoon gave way to the relentless churning of the ocean, that I realized I had gotten myself into something much bigger than intended.

On previous passages, we had always departed with much fanfare: farewell gatherings with friends, numerous last-minute trips to the store for “one more thing,” visits to customs, radio calls to other departing vessels. This was different. There was no one to witness our departure, or to mark that we had ever been there. We felt utterly alone in the world.

Steering our little 32-foot boat out through the pass and emerging into the largest ocean in the world, knowing that landfall was 4,000 miles and more than a month away, the scale of our voyage came sharply into focus. How on earth had we ended up here?

Liam and I had spent the past five years sailing Wild Rye, our 1971 Wauquiez Centurion 32, from our home port in British Columbia south to New Zealand. For most of that time, I had only the vaguest idea where the Marshall Islands were, and no expectation at all that we might go there. Beyond making it to New Zealand, our plans were hazy and formless.

By then we had begun to feel the pull of home, but we hadn’t given any thought as to how. We only knew that we couldn’t leave our stalwart vessel behind in the Southern Hemisphere. Few of the books and articles that had inspired us to explore the South Pacific offered any guidance on how we might get home again.

Decision Time

Crossing the Pacific against the prevailing trade winds is no joke. They’re a good reason why many cruisers (especially those hailing from western North America) choose to sell their boats in New Zealand or Australia. The trip from New Zealand to British Columbia is upwards of 7,000 nautical miles, with the potential for a significant portion of the sailing to be upwind.

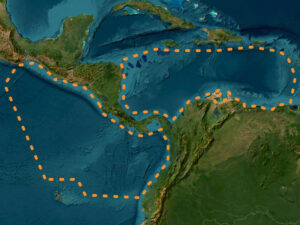

The most obvious course of action is to make use of the prevailing westerlies. One option is to sail east from New Zealand and aim for, perhaps, the Austral Islands and Marquesas, followed by Hawaii; from there, one can skirt north around the Pacific High and then head for the mainland.

Another choice is to head north until one reaches the westerlies, then turn right. Sailors taking this route would likely aim for Alaska, British Columbia or Washington.

The Southern Ocean has, on average, stronger and more-established westerlies, and the lack of landmasses allows the uninterrupted winds to churn up some impressively large swell. The North Pacific Ocean, by contrast, tends toward flukier wind patterns and smaller sea states. The latter option has the advantage of the North Pacific High, which, depending on its strength and location, can offer a helpful boost to vessels sailing east.

We had a few cruising friends who had sailed parts of both our prospective routes. Those who took the southern route, sailing from Picton, New Zealand, to Gambier Island in French Polynesia, reported 48 hours of 40-knot winds, and waves tall enough to rip their solar panel off its stand, 10 feet above the waterline. The accounts we heard of sailors taking the northern route sounded cold and foggy, with frequent gales even in summer months. Several discouraging sources also told us that for the past several years, the North Pacific High had barely materialized at all. Eastbound cruisers had been met with headwinds almost all the way across. One unlucky couple, aiming for Seattle, had somehow been pushed by contrary winds all the way to Mexico.

Liam and I decided that we would rather have the cold, potentially miserable high-latitude portion of our voyage closer to the end of the trip. We had hoped to get used to passagemaking again before encountering any truly bad weather. We would sail north from New Zealand to the Marshall Islands and cross our fingers that, by the time we were headed to Alaska in July, the Pacific High would be well-established and help to minimize the amount of upwind sailing required.

The Passage

It was late June when we arrived in Rongerik, nervous but committed to our voyage home. According to weather lore, the Pacific High should be starting to slide northward, increase in barometric pressure, and stabilize.

In reality, it looked like a tiny blob on the chart, wobbly and unreliable. Meanwhile, low after low was spinning eastward from Japan and careening across the North Pacific, with angry-looking spirals of red tracking across our prospective route.

Days and weeks passed with no improvement. I had nearly (and happily) resigned myself to spending the rest of the year in our tranquil blue lagoon, but one day, Liam checked the weather and let out a victorious cry of “This is it!” The swell was down, the northeasterly trades were blowing from due east, and the North Pacific High was expanding and sliding westward toward us.

We started out strong. By Day Three, the trades were blowing from their typical northeasterly direction, and we were closehauled in 20 knots. We sailed either closehauled or close-reaching for 10 days, sheeting in and heading up when the sea state allowed, bearing off a bit and easing the sheets when the waves were steep and crashing with too much vigor over the bow. Liam trimmed the sails obsessively, adjusting jib cars and lines. I was amazed that the minute changes in sail trim could make the difference between Rye cutting smoothly through the waves and being shoved about.

For two or three days, we were down to the third reef and storm jib, while the headwinds strengthened to 25 to 28 knots and whipped up a short, steep wave period. Time crawled to a foggy stop as we alternately tried to sleep, knees and elbows wedged tightly in place to keep us from bouncing out of the sea berth, and tried to stay awake, arms braced in the companionway, fighting the stupor that comes from so much jolting and nausea.

The trick in these conditions is to stop thinking altogether. Try to exist purely in the moment. It’s a misery meditation of sorts. There is a Buddhist concept that when we react to discomfort with aversion, we cause ourselves more pain, so the better course of action is to welcome the discomfort with open arms. I don’t claim to know much about Buddhism, but I strongly suspect that when I look back on my life years from now, any ounce of spiritual insight I possess will have come from time spent at sea.

Miraculously, after 10 days of this unpleasantness, we found the North Pacific High. The wind veered, and suddenly Rye was flying over a gorgeously flat sea, its light-air sails pulling for all they were worth as phosphorescence lit up our wake.

On the 15th day of the passage, which happened to be my birthday, we crossed the dateline that bisects the Pacific Ocean at 180 degrees of longitude. How bizarre that one can cross an invisible line and time-travel into yesterday. It was a once-in-a-lifetime chance to celebrate my birthday twice.

The next week passed in a blur. We always find that the farther we get into a passage, the more time seems to accelerate. It no longer feels painful to wake up every three or four hours. The watches go by effortlessly. When we’re on land, there’s always so much to do that my brain feels overstuffed. At sea, there’s just space, time, and the sounds of the boat and the ocean. A week passed this way, as Rye worked its way steadily clockwise around the edge of the North Pacific High through an endless sea. The only markers of miles under the keel were the falling temperature and the fog that began to blanket us every day, spilling down from the Arctic Ocean.

Eventually, our easy run came to an end, as the Pacific High deteriorated and a low-pressure system marched down from the north. We didn’t want to meet it face-to-face, so we diverted course for two days to skirt around its southern edge. And we thanked the universe for the creation of modern weather forecasting. Inaccuracy in the forecast could have meant the difference between 25 and 40 knots of wind, but we never saw more than 2 or 3 knots beyond what our forecast predicted.

Our last week at sea passed uneventfully. Sitka, Alaska, was so close that we could smell it in the briny quality of the air and feel it in the warming of the breeze off the mainland. At the tail end of a good passage, we often feel bittersweet—the anticipation of arrival mixed with sadness that the trip will soon be over, and dread of returning to a faster pace of life.

Still, every passage brings a greater sense of pride in the boat and in our own sailing abilities, and this passage in particular brought a deep sense of satisfaction. We had both wondered, on many lonely night watches, whether we were equal to the challenge. In the end, the North Pacific delivered some of the finest sailing we had experienced together. We had honed our weather-routing abilities. Above all, we were giddy about sailing back into our home port and closing the loop on the voyage that had been at the forefront of our lives for so long.

I could have used a few more days at sea to sort out the heady mix of emotions, but the winds were steady. Too soon, we emerged into the middle of a fleet of purse seiners. There, just beyond them on the horizon, was Alaska.

We had sailed close to 20,000 miles, and we still had a long trip down the Inside Passage before we could truly say we’d made it home, but pulling up to the dock in Sitka still felt like a victorious arrival.