I’m constantly asked, after more than six decades of offshore cruising and four circumnavigations, what the most difficult part of the sailing lifestyle is. The challenge now, I always pontificate, is to find a harbor where I don’t owe a lot of people a lot of money.

Yes, the most important item you can bring aboard your boat is your sense of humor—not to laugh at others, but to laugh with them as they laugh back at you. Everything marine can be humorous if you view it the right way.

Let’s take oars or propellers as examples. Many newbie sailors aren’t sure why propellers even exist on small sailboats. The truth is that mean-spirited, desk-bound designers include them to unexpectedly “suck in” dropped dock lines, stray sheets and wayward halyards. That’s right: King Neptune and his pals are sadists. There’s no other way to explain it.

Ditto inboard engines. Their job is to stop in narrow harbor entrances, up-current of jagged rocks and upwind of closing bridges. And the lowly tiller. This is an ordinary wooden stick that, once at sea, forces the person holding it to yell nasty insults at all the other folks aboard—and not quite grasp why the crew isn’t smiling.

There’s no end to the creative humiliations that sailboats provide. I’ve powered away from the dock so many times with my power cord attached that my wife thinks huge blue sparks catching the dock on fire is a normal part of casting off.

And it’s not just me. A rum-soaked Floridian friend of mine traded his fiberglass sloop for a classic wooden yawl at the Bahia Mar Resort and Yachting Center—and went sailing while hugging a bottle of rum. Alas, he wasn’t too sure how to reef his new vessel. In a relatively minor squall, he lost his mainmast over the side. It had to be cast off when it threatened to poke a hole in his semi-rotten planking in the Gulf Stream. Oh, he was bummed, though not as bummed as when he went under the (closed) 17th Street bridge an hour later and lost his mizzen as well.

My wife refuses to let me use my portable drill without supervision. Why? I once drilled through the top of our water tank. Then, to prove that my mistake wasn’t a fluke, I drilled through a picture of our daughter (which was, like, hiding on the other side of the bulkhead). No, I’ve never drilled through our hull, but, according to my long-suffering wife, it is only a matter of time.

Electrically, I’m no better. All the marine electronics I buy are filled with smoke—which usually leaks out the moment I (mis)connect them. “Did you check polarity?” my wife always asks with a smirk as their plastic cases begin to melt. I long for the good ol’ days of my sailing youth, when tube radios tuned to 2182 AM had metal chassis.

I also regularly wear wraparound Tahitian pareos around the boat. I’ve had them get entangled in my windlass, my engine’s flywheel and various other moving parts. Once, during the America’s Cup in New Zealand, while powering in front of a dock crowded with Kiwi spectators, my outboard engine lost power. I immediately whipped off its cover to wiggle its spark-plug wire. Somehow, this act yanked off my pareo and spun me around in the dinghy like a top while those on the dock covered their eyes.

Dinghies are as ego bruising as their motherships. I’ve face-planted myself coming onto beaches too fast, bonked my head standing up too quickly while going under docks and, of course, guillotined myself on a dozen evil dock lines.

Dock hoses? Oh, please! I’ve filled up many a fuel tank with water, and vice versa. Seriously, never attempt to shower with diesel fuel, no matter how dirty you are.

Booms are aptly named. The first time I was hit in the head while tacking, I vowed never to allow that to happen again—and I didn’t until a few minutes later, when the thought was knocked out of me during a jibe. Of course, now that I’m sans hair, I can knock myself out just standing up under a boom.

Don’t get me started on navigation. Once upon a time, during my celestial daze, er, days in the ’60s, it was easy to mistake Bermuda on the East Coast for Catalina Island off the West Coast. Nowadays, with modern GPS included in each toothpick that Apple sells, not so much.

Things were much more laid-back in the Caribbean when I arrived in the ’70s. For example, if people spoke French and served croissants, it was probably Fort-de-France on Martinique. If they spoke Spanish and whipped up tortillas, it was probably Mexico. Or Colombia. Or Barcelona in Spain. That’s why it was called dead reckoning, because that’s how many of us ended up when our doctors were off a thousand miles or so.

Marine radios present their own set of problems. While it is perfectly OK to talk about a September day over the VHF radio, never use the same phrase for the month between April and June, unless you want a search-and-rescue helicopter hovering overhead. Speaking of those folks, it is always good to know what ocean you’re in. It speeds things up if you can inform your rescuers about needing assistance in, say, the Pacific instead of forcing them to guess.

Why are marine toilets called heads? Well, because that’s always what they’re messing with—your head. Seriously, they do call it a joker valve, don’t they? It’s impossible to explain to a landlubber the indignities of such satanically possessed devices. I’ve been squirted so many times that I wear my heavy-weather gear while pumping. In fact, this is how foul-weather gear got its name. (Not really.)

As a result of the pandemic and my shrinking income, we hadn’t hauled in a few years. This meant we had to scrape the boat’s bottom before we went sailing. And here’s the truth of it: As an aging sailor gets arthritic, those freaking barnacles are fast. And not only that, but we’re tenacious too. I used to remove them with a putty knife. Now, I use a cold chisel and a sledgehammer.

In the tropics, ventilation is important if you live aboard, especially in places where the local cuisine includes beans, beans and more beans. Yes, wind scoops can be cruising necessities in laid-back Mexico. Tugboats aren’t the only vessels that toot. (Why exactly is Montezuma so vengeful?)

This brings us to the subject of tender traps. The bottom line? I’ve never had a dinghy I couldn’t fall out of, capsize or pitchpole. Wanna know how to swamp a dinghy? Buy a new outboard. In my experience, both will be upside down and underwater within days.

I remove the engine covers of my new outboards before I even mount them, and I paint the insides with antifouling paint. Think I’m kidding? I’ve found crabs swimming in my carburetor float. I’ve had seaweed snarling our starter cord. Our murderous dinghy drowns our outboard so often that I don’t need to tilt it up to check its prop for nicks. Hell, our lower unit needs sunblock.

Batteries? I use the lead-acid variety for the convenience of being able to remove their caps and peer inside to see if they’re full of juice. Simple, eh? Why waste money on an expensive battery monitor?

Yes, I have a laptop aboard to keep track of our finances. The moment I keyboarded in our floating home as an asset, the software quickly transferred that amount into its liability column, and then the whole screen started flashing, beeping, and proclaiming: “You’re broke, Skipper. You’re officially bankrupt in every currency in the whole watery world.” Ah, the joys of circumnavigating.

Of course, I prefer not being too negative. In fact, I once wrote a book singing the praises of cruising vessels. It fit on the back of a postage stamp.

Actually, I’d have included more positives in this article, but, if I remember correctly, my short-term retention has been poor since the ’60s. Where were we?

Don’t get me started on the customs process. Once the guys in uniforms begin asking me for money, I whip out a rubber hose from my back pocket and strike myself in the head with it. This saves time. If they ask me if I’m carrying drugs, I always reply, “None that I haven’t already ingested,” with a wink and a grin.

Regrets? None! I look back on watery life and remember all the glorious free rides I’ve had on US Coast Guard vessels, on search-and-rescue choppers, in the back of various squad cars—oh, what a lucky guy am I.

Incidentally, I’ve developed a cosmically cool way of dissuading those determined bean counters with long memories who foolishly want us to pay back the money we borrowed from them on previous circs. As they approach, I calmly inform them that there are three types of people in this world: people who can count and people who can’t.

That line usually gives us just long enough to hoist anchor and sail away. Ah, the great blue sea.

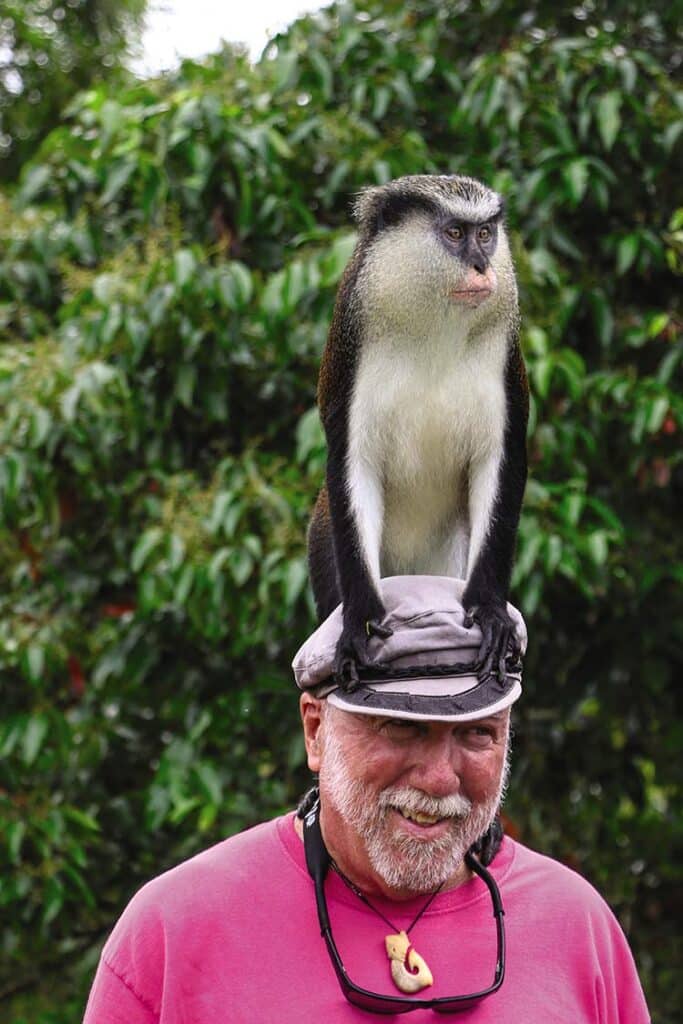

Currently on his fourth circumnavigation, Cap’n Fatty is an eternal “boat kid” who was raised aboard an Alden schooner and never grew up. He’s lived aboard for 63 years while amassing hundreds of thousands of miles under his keel and has authored a dozen books on the subject. He says his biggest problem as a serial cruiser is “finding anchorages that don’t contain people who I owe a whole lot of money to!”