There’s an alarm clock on the nightstand beside Tim Jackett’s bed in his home in Erie, Pennsylvania, but he doesn’t need it. Every weekday morning, at the otherwise sleepy hour of 5 a.m., he’s already wide awake, up and at it, ready to go. The drive to Painesville, Ohio, the current home of Tartan Yachts, is a 75-mile straight shot down I-90 that he can generally knock off in a bit over an hour (though he once got stranded on the highway for 11 long hours in a lake-effect blizzard).

Jackett started working for Tartan as a summer job in college almost 50 years ago. Though he hasn’t toiled there continuously since then, the work has been the central thread woven through his long, eventful career as a boatbuilder and naval architect. These days, he not only designs the boats at Tartan, but he also oversees the operations and production. The plant gets underway at 7 a.m. sharp, and he won’t be late.

Jackett’s a boatbuilder all right, but, to be more specific, because his roots play such an important role in who he is and what he does, he’s a Midwestern boatbuilder, a born-and-bred northeast Ohio boy, a child of Lake Erie, where his passion for sailing was kindled and the seeds of his lifelong craft were sown.

The sixth of seven kids, Jackett’s the son of a US Navy veteran who briefly set down stakes in Florida following his service in World War II but soon returned to good old Cleveland, where he and his wife were raised. The family eventually moved to the east-side suburb of Mentor, pronounced Menner: “No ‘t’ in there,” Jackett said. “If you’re from Menner, you’re from Menner.”

Jackett attended the public high school there, but, more important, the little town had a cool, cozy, communal sailing club. It was a no-frills outfit (unlike the nearby hoity-toity yacht club) where his parents sailed their little wooden sailboat, a Privateer named Jacquette (the original spelling of the family name, in honor of the old man’s French-Canadian heritage). That club is where the racing bug bit Jackett.

“There certainly wasn’t any junior sailing program, but it was a great place,” he said. “We were kind of the outcasts. We raced on Thursday nights because the yacht club raced on Wednesdays. And we used their marks. We did try to be courteous about it, but, yeah, we were the hoodlums across the water.”

Following high school, Jackett applied to exactly one college: the tiny, focused Cleveland Institute of Art. “I thought I was going to be a painter,” he said. “I was a bit of a loner at that point, and going up on a mountaintop somewhere and painting sounded pretty good. But my very practical dad didn’t think much of that as a career choice and encouraged me to go from the fine-arts side to the more-commercial program, which was industrial design. So I went down that path. And I spent my whole time there drawing boats. I got a copy of Skene’s Elements of Yacht Design and learned how to draw lines plans. When everyone else was drawing toasters and headlights, I was drawing boats.”

The boat-crazed lad searching to find his place on the watery planet went through a family friend to land the ideal summer gig: as a gofer at the busy local boatbuilding concern, Tartan Yachts. Launched in 1951 and originally called Douglass & McLeod after its two founders, the company switched in 1961 from building small one-design racing dinghies and launched the Sparkman & Stephens-designed Tartan 27, a wild success commercially and on the racecourse. By the mid-1970s, however, after a fire wiped out the company’s base in Grand River, it was owned and run by a passionate sailor named Charlie Britton, who would come to play a major mentoring role in Jackett’s life.

Jackett’s job involved mostly warranty work, though he once leapt into murky Lake Erie to see if one could reattach a centerboard pennant on a Tartan 37C without hauling the boat (one could). During the couple of summers that he worked there, he never actually crossed paths meaningfully with Britton. That all changed thanks to, of all things, a local bar called the Beachcomber that the after-work Tartan crew frequented.

Jackett’s sister was a friend of the owner, who wondered if her art-school brother could build a model sailboat to display in the center of the joint. (If you strolled to the men’s room, you couldn’t miss Jackett’s framed boat renderings from his college classes lining the walls.) Jackett was mightily enamored of the slick Tartan 41, of which there were several on the lake, including the one campaigned by Britton.

“I’d spent a lot of time looking at the boat and found a brochure and decided to do the 41,” he said. “The model was fully rigged, sheathed in fiberglass, had the keel, winches, everything. Charlie had a look and asked, ‘Who the hell made that?’ And that’s when I got to know him a bit.”

That first impression proved lasting. The summer after graduating, in 1977, at the tender age of 22, he was hired full time at Tartan. Little did he know then, but he’d embarked upon his lifelong pursuit.

If, at the time, jackett had any inkling about the tenuous future of American production boatbuilding, or about the twisting, turning marine-industry journey that lay ahead of him personally, he just might’ve packed up his easel and headed for the hills. In the moment, however, there was no time for deep contemplation. His first project was the 33-foot, one-design Tartan Ten racer, and it was full-on.

Britton was betting the farm on the boat, with the ambitious goal of having 40 boats on the starting line the following season (other than the prototype, none had actually been built). Sparkman & Stephens had drafted the lines for the hull but little else. So, Britton set up Jackett in the development shop with a drafting table and told him to get to work.

“I ended up doing the deck design and what little interior there was to it,” he said. “Charlie was a product guy, not a designer, but he loved the development side of it. If you had a sketch, he’d put his notes all over it. And we’d sit down and talk about stuff, and I’d take his thoughts and help him turn it into what we were trying to do. I felt really privileged to work with Charlie. He was such an experienced sailor.”

Collaborating with Britton on this inaugural effort was an almost perfect introduction to the business of creating yachts for a consumer market. And it would lay the groundwork for so much more to come. But working with Britton was also an adventure because it was almost never exactly clear what would happen next.

For instance, the union situation in Ohio was problematic, so much so that Britton shut down the production floor and moved that whole shooting match to Tartan’s second facility, in Hamlet, North Carolina, to which Jackett was also dispatched. In Hamlet, Jackett graduated from conjuring deck layouts to engineering entire systems, with Britton once again looking over his shoulder and working through problems and challenges. “It was a great experience,” he said. “Talk about a hands-on education.”

Also in Hamlet—because what else was a boatbuilder going to do with his time off—Jackett decided to rent a little shop and design loft, and build his own cold-molded, 24-foot-6-inch racing sloop (it was actually his second personal boat, having completed one earlier in Ohio).

“I’d work all day at Tartan, grab a six-pack, and go to work on my next boat,” he said. “One day I’m down on my hands and knees, and Charlie comes in and says, ‘What are you doing?’ And I tell him I’m building my next boat. Next thing you know, he’s down there on his hands and knees with me.” The sensei and student, back at it.

Like Jackett, Britton always had a side project going; under the auspices of a company he called Britton Marine, he commissioned Southern California naval architect Doug Peterson to draw a powerful 43-foot offshore racer, exposing Jackett to yet another facet of design work and the approach of a renowned designer. But the move also signaled Britton’s own growing wariness with union labor and Tartan in general. In 1984, he pulled the plug and put it up for sale.

Partners John Richards and Jim Briggs (of Briggs & Stratton power-equipment fame) were the next owners, and their five-year tenure was characterized by missteps and false starts. But Jackett said that he will forever be indebted to them for one satisfying opportunity: to design his own boat, soup to nuts, the Tartan 31.

“Charlie was so enamored of Sparkman & Stephens,” he said. “I don’t know that he ever would’ve given me free rein to be the complete designer of the product. I made my pitch to John and Jim, and they said, ‘OK, we’ll do it.’ At that time, the development cost for a 31-foot boat was about $400,000. At that point, I’m like 30 years old, and I’ve got a company committing major resources to something that I conceived and drew up. It was cool.”

The new owners’ confidence was not misplaced; the production run for the 31 totaled 165 units, which made it profitable. The design also earned a Cruising World Boat of the Year award, which made it a critical success. Moreover, it gave Jackett a new title: chief designer of Tartan Yachts.

But Briggs and Richards weren’t in it for the long haul. When they decided to bail out in 1990, Jackett took the molds for a Tartan side effort called the Thomas 35, a one-design racer, and hung out his own shingle to build them: Jackett Yachts. Which is just about the time everything once again came to a fork in the road. A businessman named Bill Ross picked up the Tartan pieces and lured Jackett back into the fold, this time not only as the brand’s designer, but also as chief of operations.

Ross cared little about boats, per se; his expertise lay in finding distressed companies and making them whole. His stewardship was oftentimes a rough ride down a road littered with potholes. But two significant events occurred during the time he owned the place. The first, in 1996, was acquiring the popular, longtime Canadian brand, C&C Yachts. Jackett was thrilled, and in rapid order designed three C&C’s: the 110, 99 and 121, of which some 400 yachts would eventually be built.

“They were my favorite boats growing up, even more than Tartans,” he said. “Really good performers, more toward the racing side, and now we could take on

J/Boats a little bit. The two brands worked together very well. Dealers were hungry for them. It was a really smart move. I stopped racing my own little boats and started racing the C&Cs I designed. I took the 99 to Key West and did some nice events with it. It was all fun stuff.”

The second seismic shift happened in the late 1990s. With their Fairport, Ohio, plant bursting at the seams, Ross enlisted the services of a fellow named John Brodie, who was exporting some of Tartan’s stainless-steel parts from a facility in China, to build the Tartan 4600 there. The tooling was loaded on a ship, and Jackett landed in China the same day the molds arrived. After inspecting the decrepit infrastructure, he almost immediately realized that the entire idea was disastrous and wouldn’t work.

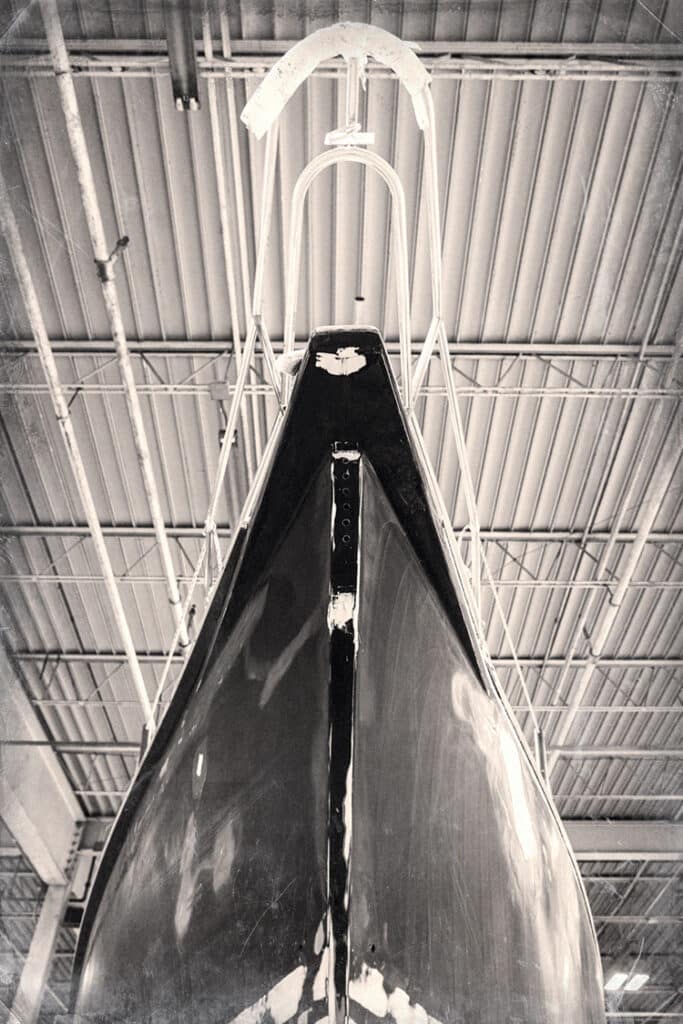

But one significant development arose from the otherwise failed experiment: Brodie wanted to build the boats in high-tech, vacuum-bagged, two-part epoxy laminates—a superior mode of construction—and Ross was all in. He told Jackett to make it happen (his arm didn’t need twisting; he’d been employing West System epoxy, which he loved, on his own cold-molded boats for years). Jackett enlisted some of the top names in materials and composite structures, eventually bringing all the new technology to the Ohio floor. At the same time, Tartan acquired an autoclave and started fashioning its own carbon-fiber rigs and parts. It was a major shift in how the boats were built, and, for that matter, marketed.

“All of that dovetailed into our advertising, which Bill was really smart about,” Jackett said. “It was all about ‘engineered to perform.’ Audi was running a similar marketing program at the time, and Bill didn’t mind plagiarizing from the auto industry. It was an important element back then, and it still is. Our boats are different from a run-of-the-mill production boat.”

But the roller-coaster ride was far from over. The early 2000s were good years for Tartan, right up to the Great Recession of 2008, when the hammer fell on the entire economy. Tartan wasn’t immune: Ross sold out. Jackett Yachts reopened for business. There was a collaboration with Island Packet on a boat called the Blue Jacket 40; the launching of a new little daysailer, the Fantail; and the acquisition of the Legacy powerboat brand from Freedom Yachts. In 2014, thanks to the Legacy business he brought with him, Jackett teamed up with Tartan’s latest owners and rejoined the firm.

If Jackett had never done another thing in the marine industry, you could say he’d enjoyed a rewarding, stellar career. But it turns out that there was another chapter yet to unfold.

the heart attack—yes, heart attack—that Jackett suffered after racing sailboats on Lake Erie this past August was certainly unexpected. At first, he thought the tightness in his chest was from sitting too long in an awkward position on the boat. Once ashore, he realized it was something far more serious. Quick action by several folks at his yacht club averted what otherwise might’ve been tragic. And he was a lucky dude indeed, surviving with all systems intact and sparking.

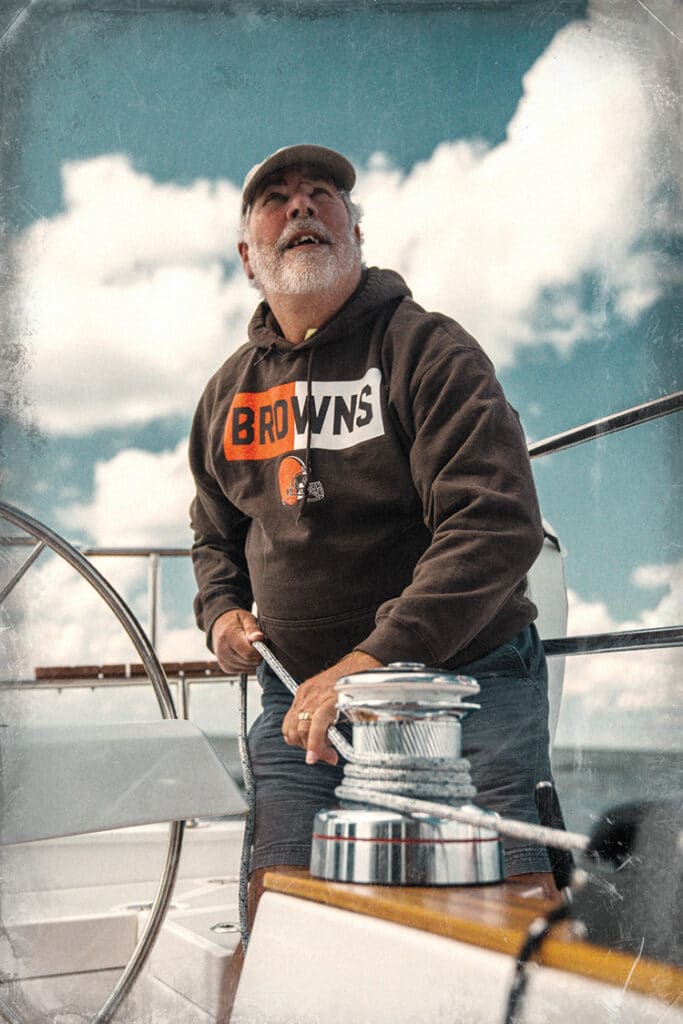

I learned of Jackett’s health situation and other personal matters on a visit to the Painesville plant this past September while on an assignment to review the Tartan 455, his latest design. It’s a pretty sweet, powerful sailboat, with a raised deckhouse very much outside his usual purview. But as I discovered on a windy test drive on Lake Erie, like every Jackett design I’ve ever helmed, you get some sail up and it will haul the mail. So there was no real surprise there. Instead, the surprises came, one after the next, on a tour of the factory.

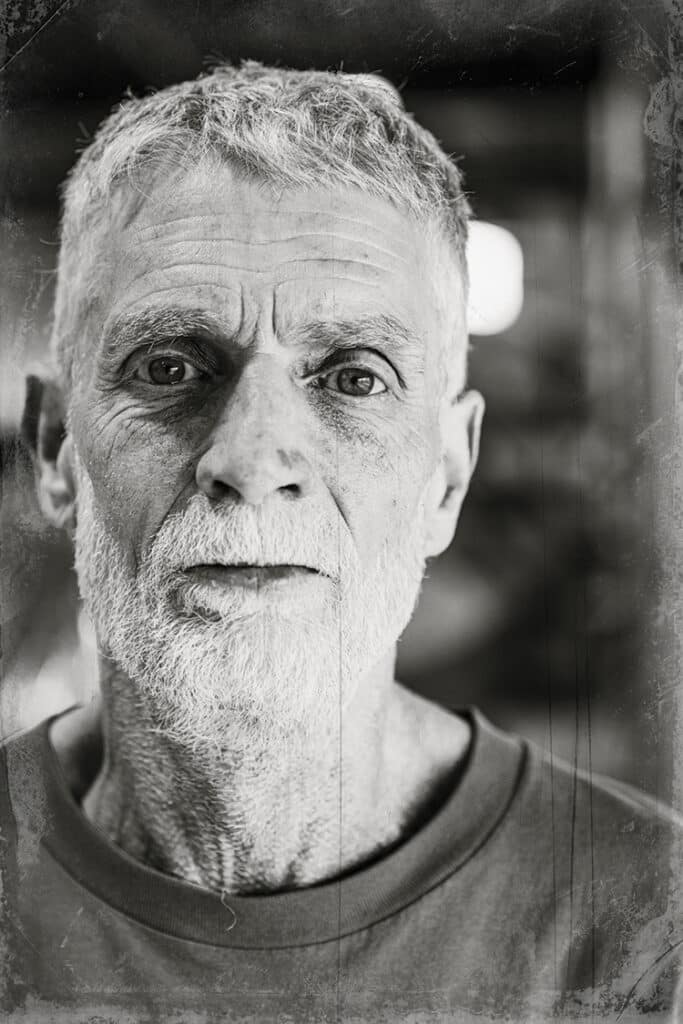

It was bustling place full of frenetic activity but with a palpable feeling of camaraderie and purpose. Pink Floyd blared from the wood shop. A makeshift help-wanted sign was placed near the entrance: “Marine Mfg, Now Hiring, Apply Inside.” Jackett was bearded (his last shave was the day he graduated from high school; his wife, Donna, and their three kids have never seen him without it) and bedecked in a Cleveland Browns hoodie (his beloved Brownies were playing that evening on Monday Night Football), and he looked every bit the image of the burly, no-nonsense Midwestern boatbuilder. He was clearly quite proud to show some visitors around. “We make two things here,” he said by way of introduction. “Boats and dust.”

At the front of the shop, a trio of older Tartans, including a 4400 that had been thrashed in the Bahamas during Hurricane Dorian, were undergoing complete refits, which is a welcome and steady stream of business. Around the corner, a new rudder was being cast for a Tartan 37C. If you have an older Tartan that needs parts or an upgrade—“regardless of vintage,” Jackett said—the company’s happy to address it for you.

The hulls and decks for several new Tartan 365s, one of three models currently in production, including the 395 and the 455, were in various stages of construction. The 365 is Jackett’s latest critical triumph, the Cruising World Domestic Boat of the Year for 2022 and one of his 31 overall designs, including the C&Cs and the five backyard boats he ultimately built. (When complimented on that impressive number, he cracked, “We become prolific and old at the same time.”) In the rigging shop, a worker was laying up swaths of carbon fiber, straight out of the fridge, in the autoclave for a new spar. Out back, the original Tartan 27, Hull No. 1, was propped up and ready for a complete makeover, set to coincide with the 65th anniversary of its launching in 2025.

Jackett led us from the factory floor to the stairs and his second-floor office, where a window overlooks the entire hectic scene (and where his contented pooch, Ella, a German shepherd/husky mix, waited patiently). At the foot of the staircase was a pair of sneakers painted gold and mounted on a plaque.

“That’s the Golden Tennis Shoe Award,” he said with a laugh, “for the guy most improved in staying at his workstation and not wearing out his shoes.”

This is where Seattle Yachts, the latest entity to own Tartan, comes in. In early, pre-pandemic 2020, Jackett was running the place with Rob Fuller, but matters “reached a financial rough point.” They reached out to Peter Whiting, a managing partner of Seattle Yachts, an established Tartan dealer that had several boats on order. Whiting paid a visit to the plant. And, in rather short order, Seattle Yachts took over Tartan Yachts. It was a strong move by the Pacific Northwest firm to commit to a good, old American brand.

Originally a brokerage office, Seattle Yachts had pivoted into boatbuilding and owned several brands. After purchasing Tartan, it made several six-figure investments, including the purchase of the new plant in Painesville. Eventually, the new owners put Jackett back in charge of overall operations. Always a stickler for running things efficiently and incentivizing his workers, Jackett witnessed a few too many folks taking too many breaks. Hence, the Golden Tennis Shoe Award for sticking to the task at hand, one of several new employee incentive programs.

The new overall responsibilities have once again changed Jackett’s life, adding a daily commute back and forth from Erie, where he’d moved to be closer to his grandchildren. On top of everything else—actually, more than anything else—Jackett’s a family man, and being closer to his kids is a huge priority as he navigates his 60s. Taken in context with his recent health scare, this desire leads to inevitable questions. Like, do you ever consider wrapping up your career? And what, exactly, does it feel like to be one of the business’s lone survivors, the proverbial last man standing?

The answers took some of those old twists and turns. Under a photo on his office wall of the Tartan 31 under full sail—his first design, and still a fond memory—he offered a few thoughtful responses.

Sure, he’s given some thought to moving on, but he needs a successor, someone he trusts, to whom he can pass the baton. He enjoys the operations side of management, building the team. He’s proud of continuing the long manufacturing tradition in northeast Ohio. He likes the fact that he’s there for owners of older Tartans, that when you buy one of his boats, you join the Tartan family. And the feeling he gets when setting the sails of a new design after months of hard work, that initial rush as it heels into the breeze, remains a cherished one.

But what about it, Tim? How long?

“There’s a country song that asks that question: ‘What would you be doing if you weren’t doing this?’ And the answer is: ‘I’d be doing this,’” he said. “Maybe not with Tartan, but maybe I’d set up a little shop and build my own cold-molded 25-foot boats. Just for the pleasure of building them, putting them in the water, and sailing them.”

Once a boatbuilder, always a boatbuilder.

Jackett had one last remembrance and anecdote to share. Fittingly, it goes back to where this story began, on that nightstand in Erie, next to the useless alarm clock.

“Back in the mid-1980s, I actually sent a job application to Sabre Yachts, and I asked Charlie Britton to write a letter of recommendation,” Jackett said. “And he wrote one, in longhand. I tell people, you have your wooden box that you keep by your bed, and Charlie’s letter is in there. He was a man’s man, and there’s a line in there that I really appreciated: ‘The men have respect for you.’

“And that’s a cool statement, you know?”

Herb McCormick is a CW editor-at-large.