ClinkerSt

Last September, we announced Cruising World’s Westlawn/Island Packet Yachts Design Competition, reviving a tradition that dates to the 1980s. The competition’s purpose was to “encourage and highlight new and exciting designs for serious cruising under sail.” The announcement unleashed a veritable explosion of creativity, and when the deadline arrived on March 1, the in-box at Westlawn groaned under the combined output of 53 yacht designers from 12 countries.

Flattered, I readily accepted Cruising World’s invitation to be a judge. Others-Dave Gerr, the director of Westlawn Institute of Marine Technology, Norm Nudelman, the provost of Westlawn, and Chris Wentz, the president of Z-Sails (hereafter referred to collectively as the Westlawn Group)-took on the initial heavy lifting for the judges. They spent a day going over each one of the entries, then skimmed the best 10 off the pool for the rest of the panel-Bob Johnson, the founder and president of Island Packet Yachts; Rod Johnstone, the co-founder of J/Boats; Bruce King, an eminent yacht designer; and me-to review.

The finalists hailed from five countries, and they banged every corner of the envelope, from a superlight, superfast (and, at 57 feet, rather large) catamaran with accommodations in a pod to a boxy, plywood monohull with triple chines.

To encourage as many entries as possible in this revived competition, the design brief was loose. The basic requirement was for a boat between 30 and 60 feet LOA capable of serious cruising with two or more people for a minimum of three weeks. Entrants were asked also to submit a “mission statement” of up to 1,000 words in which to refine objectives; some designers let themselves-and their designs-down by not using this requirement to their best advantage.

Each of the judges graded the designs from 1 to 10, using the parameters set out in the competition rules and some of their own, and the final tally was a simple arithmetical average of each design’s scores. Each judge has his own gazing mirror, so there was quite a spread of ratings, but all concurred that the designs that floated to the top deserved to be there.

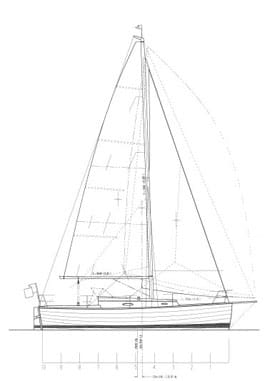

The winning designer, Richard Boult, of the rugged Australian island state of Tasmania, wrote a succinct but detailed mission statement and followed it through to deliver a lovely-looking sailboat and a novel take on an old construction technique with which to build it. In many ways, his Quick Clinker 31 embraces the spirit of the design competition of years ago, which elicited many variations on the theme of “Go simple, go now.” He won over most of the judges with his boat’s “clean hull lines and appearance” (Johnstone), “very thoroughly thought-out construction” (King), and “simple, straightforward arrangement” (the Westlawn Group). I faulted the design for being scant on such cruising necessities as light and ventilation in the cabin and a clearly defined anchoring system. Johnson thought it “attractive” but “too small,” and he asked, “Who wants wood?”

Nevertheless, we both gave it high marks for the same reasons the others did. (For more about the Clinker, click here.)

Bruce King’s comment-“Nice presentation of a contemporary design”-echoes most of the judges’ thoughts about the runner-up, a 57-foot sloop from Keimpe Reitsma, who lives in the Netherlands, though Bob Johnson noted that it would be expensive simply because of its size.

In third place, Paulo Bisol’s Deep Blue 48 also impressed the judges with its “nice, attractive profile [and] good presentation” (the Westlawn Group), but some felt it might be tender and suggested that its displacement target was overly optimistic.

All the judges were excited by the volume and variety of entries, compelling evidence that the cruising dream still fires imaginations with ideas, from the weird to the worldly, for making it come true. There is, certainly, a boat to fit every voyage.

Gerr, with his colleagues at Westlawn, guides countless aspiring designers toward professionalism, and for him, design competitions make valuable contributions to both teaching and learning. “I’ve long missed the design competitions that were more common 15 or so years ago,” he says. “Not only do they encourage new thinking and promote new designs; they also make sailors aware of the design considerations central to their choices in boats.”

Johnson, who suggested and sponsored this competition, did so in the hopes that it “would both encourage and spotlight independent design thought that could have a positive influence on and advance the state of the art of cruising-boat design.” The great number and variety of entries received “speaks to both the broad reach of Cruising World magazine and the great appeal of the design challenge,” he says. “I hope that we’ll be able to continue with more such competitions in the future, allowing the talents of the world’s sailing and design community to have an influence on the future of cruising sailboats.”

Richard Boult received a choice of either a $1,000 prize or a $2,000 scholarship to Westlawn. The judges and Cruising World congratulate him on his well-reasoned and interesting design.

Yacht designer Jeremy McGeary is a CW contributing editor.

To view renderings of each design, click here.