CW_0301_TIM_04.jpg

One boat had the best aft cabin Carol Hasse has ever seen, and another, the sweetest woodwork. One boat had fellow judge Skip Moyer’s favorite system for deploying and retrieving anchors. Still another treated Ralph Naranjo to his most thrilling ride in a week of sailing 30 boats.

But none of these earned the title of Cruising World Boat of the Year for 2003.

The winning vessel was the one that most effectively brought together all the complementary features that make up a seaworthy cruising boat–design, structure, deck layout, rig, cabin arrangement, systems installation, aesthetics, sailing dexterity, and, not lastly, price.

We grouped the nominees into five categories–four of monohulls, based on size and cost, and one of multihulls–and also awarded prizes for Best Value and Most Innovative. The average length was 42 feet; the average price was $348,000.

Those are the facts. In the pages ahead, were honored to present Cruising Worlds choices for the best boats for 2003.

Best Production Cruiser Under $150,000: Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 32

In the entry-level class of this years new sailboat models, we sailed seven boats under 40 feet and $150,000. We were pleased to see several here under 33 feet and $100,000, a range that in recent years had been altogether missing.

The most friendly of these for a first-time sailor is the trailerable Horizon Cat, a 20-foot cat-rigged monohull from Com-Pac Yachts in Clearwater, Florida. Carol called it a “sweet daysailer, maybe a weekend camper, thats pretty in profile” and at $35,000, “certainly a nice price for a young family to get out on the water.”

From the smaller boats, one intriguing entry was the Etap 32s. Built in Belgium by a yard that has staked out unsinkability as its market niche, the Etap brings together several novel features, including a shoal-draft tandem keel, a vertical tiller, and a removable mainsheet traveler to open up cockpit space when the boats moored. The keel is fashioned of two separate fore-and-aft foils, joined by a plate across the bottom; Ralph credits it for giving the boat a lot of lift while drawing only four feet three inches. The steering system is akin to the vertical tillers found on some launch boats; Delrin rack-and-pinion gears join the tiller to the rudderstock. “The helm felt balanced,” said Carol. “It was a boat that really made me smile when I was sailing it.” Of course, the Etap asks sailors to rate the priority of unsinkability in a 32-footer. Said Ralph, “The tradeoff for four cubic meters of foam is a little less storage.”

Elsewhere in the category, we saw strides in production techniques, particularly among European builders. One of several yards from the French Vendée region, Jeanneau has invested in expensive tooling to build decks using resin-transfer technology. Glass fiber is placed between steel male and female molds; the edges of the molds are sealed, and resin is then pumped through the laminate. Its a technique that many yards use to build small parts for galleys or heads or lockers, but this was the first year wed seen parts as large as decks built from it. One advantage of resin transfer is that it renders parts finished on two sides with gelcoat.

Two new boats from Jeanneau were built this way, the Sun Odyssey 32 and the Sun Odyssey 35. The deck on each boat is solid uncored fiberglass, but because it requires no liner, the finished deck is lighter; also, its easy to access deck fittings from belowdecks.

In both the 32 and the 35, the beam is carried well aft to make room for a cabin underneath the cockpit.

From nearby La Rochelle, France, Dufour came to the show with two new models, the GibSea 37 and the GibSea 41. The decks on both the 37 and the 41 are cored to save weight, though creaking sounds when people walked on deck gave the judges some concern. Owners of the 37 can choose either a two-cabin or three-cabin layout.

In the hills near Wurzburg, Germany, Bavaria Yachts has just undergone a major expansion that will bring its production capacity to near 4,000 boats per year, placing it firmly among the worlds two or three most prolific sailboat builders. The decks, once theyve been laid up by hand, spend between 90 minutes and two hours with a robot that cuts out every opening and drills and taps every hole for deck hardware, a process that brings the tools of automaking to boatbuilding. The Bavaria 36 is an aft-cabin sloop that, like the GibSea, is available in either two-cabin or three-cabin versions.

From a yard closer to home, we also sailed the new Catalina 350. Catalina designer Gerry Douglas created a 35-footer thats comfortable for a couple–with a separate shower stall, six-foot-nine-inch headroom, lots of ventilation below, and cockpit settees you can sleep on. While the judges saw quality-control lapses in the nooks and crannies and would have preferred not to see hatches in the swim step that open into the accommodation, the execution of many details was excellent. “The electrical panel is as good as it gets, and all the tanks can be easily removed,” said Skip.

Of these seven, the boat the judges liked best was also one of the least expensive: the Jeanneau Sun Odyssey 32. “Perfect balance,” said Ralph of the steering. “This is an autopilots dream.” Pushed along at 6.7 knots by an 18-horsepower Yanmar, she was a quiet boat under power, with 81-decibel sound readings in the saloon (OSHA deems harmful more than eight hours of exposure to noise above 85 decibels). In around 10 knots of breeze, she sailed at just over 6 knots. The judges might have changed a few things–the furling line for the genoa drum runs across the foredeck to the cabin top, for instance, creating a tripping hazard and adding friction to the system. But all in all, its a boat that should bring lots of fun on the water at an attractive price.

Best Midsize Cruiser Under $250,000: Beneteau 423

We sailed five boats between 41 and 43 feet with sailaway prices between $180,000 and $215,000, each of them from big-volume production builders.

From Beneteau, we sailed two new 42-footers built on Groupe Finot-designed hulls: the Beneteau 42 Center Cockpit and the Beneteau 423. From a bulkhead-mounted seat aboard the 42 CC, the helmsman is completely protected from wind and rain. Visibility forward through the hard dodgers acrylic windows is good, though an overhead window would improve the view of the mainsail. The center cockpit makes room for, as Skip said, “a huge engine room” and a spacious aft cabin.

As for the aft-cockpit 423, Skip described her as “a lot of boat for 42 feet and for $180,000.” Like her sister, shes built with a grid structure bonded in with polyester putty, then a liner to further stiffen the hull. Its “good engineering,” said Ralph, though the liner isnt removable for refits down the line. And she lacks her siblings great engine access. But her performance stands out. At 2,400 rpm, she powered at 7.8 knots, with moderate sound readings of just 77 decibels in the forward cabin and 87 decibels at the engine box. In 12 knots of breeze, she delivered as much as 7.6 knots of boat speed on the wind. Most of all, shes a pleasure to steer. The helmsman has access to the genoa sheets but not to the mainsheet.

The Bavaria 41 and the GibSea 41, like all the new models in both lines, are designed by J&J; Design in Slovenia. The Bavaria, fitted out with a Volvo 55-horsepower diesel and sail drive, was also among the quietest boats under power, with sound readings between 74 decibels and 78 decibels as we motored at nearly 8 knots. She showed signs of hasty construction; in the cockpit, machine screws were used as spacers under an ill-fitting locker lid, and no nuts were installed on the bolts for its smallish hinges; a failure of those hinges would leave a big opening into the boat. As for the GibSea, she offers a layout that could be ideal for charters or partnerships. One option provides for three private cabins and three heads.

The most spacious boat in this category is the Hunter 426 Deck Saloon, with a displacement of 23,600 pounds, or 4,000 pounds more than the 42-foot center-cockpit Beneteau. Built in Alachua, Florida, the Hunter drew accolades for its systems installations. “These guys really adhere to ABYC standards,” said Skip. “The propane was good, the wiring was good, and the plumbing for the fresh water has a nice manifold where it all comes together neatly.” Running the 56-horsepower Yanmar at 3,200 rpm with a boat speed of 7.1 knots, we found this boat among the loudest in the fleet. Sound readings came in between 94 decibels and 97 decibels. Under sail, the boat showed adequate but not outstanding performance. In 10 knots of breeze, we saw on-the-wind speeds in the high 5s; off-the-wind speeds were between 4.2 and 4.6 knots. On this boat, too, Ralph pointed out small locker hinges–in this case, on ungasketed locker lids in the swim step near the waterline that open directly to the accommodation. All the judges felt a roachy mainsail on slides would make better use of the three-point B&R; rig than did the in-mast furling mainsail we used.

Of these, the vessel that best brought together all the attributes of an enjoyable cruising sailboat was the Beneteau 423. About her handling under sail, Ralph said, “She reflects the Group Finot capability in naval architecture.” Said Carol, “She felt solid and stiff below, and I really enjoyed the way she sailed.”

Best Midsize Cruiser Under $400,000: Hallberg-Rassy 43

The Malö 41, the Sabre 426, and the Hallberg-Rassy 43: Here are three boats that are the same length as those in the previous group but with prices $150,000 higher. How can they account for the difference?

The two simple answers are man-hours and handcraftsmanship.

From the first wow factor you feel when you step into the cabins to the details you uncover the deeper you dig, what Skip said of the Sabre could be true of any member of this trio: “This is a boat I could be proud of–proud to own and proud to sail.”

Of the Malös joinery, he said, “That companionway ladder with its inlaid wood for nonskid–you could take it out and put it in the Museum of Modern Art. Its stunning.”

Consider the humble deck locker. “All the locker hatches on deck drain,” said Skip of the Hallberg-Rassy. “They have big rubber gaskets on them and big dogs. Every locker I looked in was dry.”

Look inside the lockers below. “You just couldnt find anything that had been overlooked,” he said of the Malö. “Nothing that hadnt been sanded smooth. You could rub your fingers in places you couldnt possibly see, and the edges were all finished. It was spectacular.” Aboard the Sabre: “All the drawers are dovetailed and on rails that moved beautifully. And the doors have self-closing hinges. When you get them close, they shut.”

On each of these boats, cleats, stanchions, and winches are substantially backed. The engineering, wiring, and plumbing on all three boats, especially the Sabre and Malö, were impeccable. The decks of all three boat were easy to navigate. “No ducking around shrouds,” said Skip.

Of course, every boat has its compromises. The Malö and Hallberg-Rassy shared a trait that Ralph liked least: teak decks screwed into a cored sandwich structure. “The reality of those decks,” he said, “is that 15 years down the road, youre facing a significant repair or refit bill.”

Both the Malö and the Hallberg-Rassy feature hard dodgers over the companionway and part of the cockpit. The Sabre, by contrast, has a companionway hatch recessed far enough forward to accommodate a comfortable ladder angle but a dodger that shelters little of the cockpit. “The dodger solved water down the hatch but gave poor protection for the crew,” said Ralph.

Of the Sabres rig, which is a three-spreader Hall Spars mast supported by continuous rod rigging and a hydraulic backstay, Carol said, “Call me old-fashioned, but I would prefer to go to sea with wire rigging. To take advantage of that rig, youd have to be on the hydraulic backstay. Thats neat for the performance cruiser, but I would just prefer simple die-form wire and spreaders that are in-line rather than raked aft, so that youre not compromising downwind performance. But I do like that its continuous, so you dont have to go through gyrations to tune it.”

Of these three boats, the judges felt the Malö has the best interior and the Sabre, the peppiest performance. But for the most well-rounded doublehanded passagemaker, the award goes to the Hallberg-Rassy.

“For me,” said Ralph, “her performance was that of a Frers pedigree.”

“From the helm of the Hallberg-Rassy, everything seemed very manageable,” said Carol.

“Sailing the boat, I was very surprised,” said Skip. “It tracked like a locomotive. I walked away from the helm, left my hand off for 40 seconds, and it didnt move a degree.” An impressive performance.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| (C) Billy Black|

| |

|

|

| |

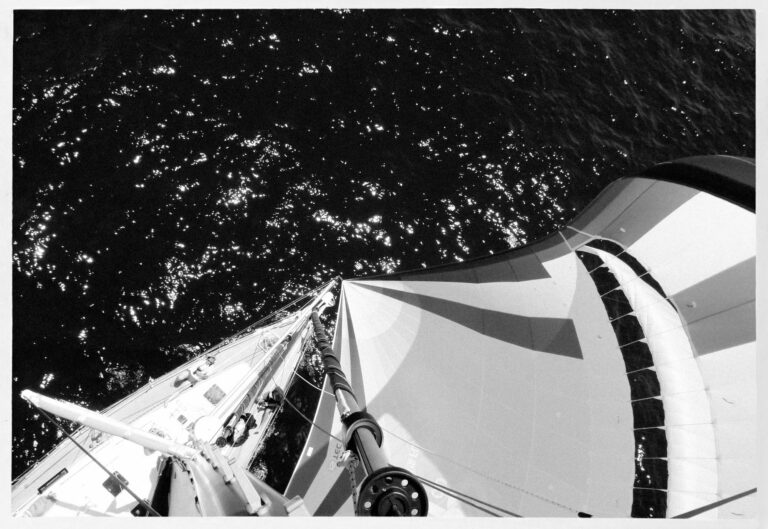

| The Rodger Martin-designed Aerodyne 47, described by one judge as “a detuned thoroughbred,” uses its slippery hull to good cruising ends.* * *|

| |

|

|

| Best Full-Size Cruiser: Aerodyne 47

At the top end of our monohull category, we sailed six boats between 44 and 48 feet and between $485,000 and $800,000. Four of the six are center-cockpit cruisers; the aft-cockpit boats represent two very different variations on the performance-cruiser theme.

From this years fleet, the boat that most boldly addressed the dichotomy between sailing performance and shoal-water accessibility is the Southerly 135 Series Three. Shes a 44-foot center-cockpit cruiser with a swing keel whose draft ranges from two feet six inches for beaching to nine feet eight inches for beating upwind in deep water. For Ralph, a downside of the swing-keel arrangement was that the two-inch-diameter pin couldnt be checked without a big yard bill. Her British builder, Northshore Yachts, has over 800 boats to its credit from 22 years in business. With her board down a third of its total draft, the Southerly sailed nicely, delivering 7.8 knots in 12 to 15 knots of breeze. Ralph credited her with a forgiving helm. “She held her way regardless of how inattentive you were,” he said. Skip found her to be “a smart, shippy boat” with “excellent seacocks.” Carol liked the “good access to the mainsheet right behind the helm.” All the judges felt that her interior, which is broken up into several small spaces, would be better suited to cooler latitudes than warm ones. “The two-foot-six-inch draft certainly opens up cruising grounds,” said Ralph.

The Najad 460 was built on Swedens western coast–on the same island, in fact, where Hallberg-Rassys and Malös are built. She shares many traits with her kin, for better (sumptuous interior joinery and beautiful systems installations) and worse (teak decks screwed into a cored substrate). As Hallberg-Rassy did several years ago when it hired Germán Frers, Najad has recently undertaken a design shift toward better performance; in Najads case, the Dutch-based Judel & Vrolijk team, known for its Admirals Cup successes, has done the revamping. Her smooth-running turbocharged Yanmar pushed the boat quietly at over 8 knots, with sound readings between 77 decibels and 81 decibels. We sailed her in zephyrs under 5 knots, and still she delivered boat speeds over 3 knots. “This is impressive!” said Skip as we (briefly) held ground with the Swan 45.

Two of the center-cockpit boats we sailed–the Island Packet 485 and the Morris 46 RS–mark departures for their decades-old American builders; neither has built a center-cockpit boat before.

Island Packets new flagship, the 485, retains many of the familiar traits of its forebears: the cutter rig with Hoyt staysail boom, the large sugar-scoop swim step aft, and the careful attention to systems installations. “This electrical panel was one of the best weve seen,” said Skip. Aesthetically, the boat looks high: The foot of the mainsail hangs 12 feet seven inches above the waterline. Under power, she was loud, with 97-decibel sound readings in the aft cabin as the turbocharged, 100-horsepower Yanmar pushed us at 8 knots. Skip liked seeing a ground plane already installed for single-sideband reception. “Of all the boats, Hallberg-Rassy and Malö were the only other boats that did that. Thats super,” he said.

Chuck Paines challenge as he drew the lines of the new Morris 46 RS was to avoid the boxy look of so many midcockpit boats. A limit he set for himself was to keep the cabin house lower than the lifelines; to make the best use of cabin volume, he traded the usual Morris bulwarks for toerails. “Her hull sheer is sweet,” said Skip. “Chuck Paines done a superb job with the lines.” The accommodations are luxurious in execution yet simple in design: two cabins, two heads, good sea berths. “I love the woodwork, and this is the best aft cabin Ive been in,” said Carol. Under power, her noise was moderate. “Her cockpit sole vibrated under power,” said Skip. A nonoverlapping jib allowed for effective closehauled sheeting with outboard chainplates. “Shes a nice shorthanded boat,” said Ralph about sailing the Morris.

The two aft-cockpit boats in this group are the Swan 45 and the Aerodyne 47. Each puts performance to a different use.

The Nautor Group markets its new 45-footer as a cruiser/racer, though after sailing her, the judges placed her well over to the racing side of that continuum. On the wind in 12 knots of breeze, she treated us to a thrilling ride, with speeds in the low 8s. Flaking the 819-square-foot mainsail made three fit men work hard, but steering the boat “was like driving a Porsche,” said Ralph. Still, he and Skip found idiosyncrasies at the helm. “This was the first boat Ive ever been on that when you downed the traveler or blew the sheet, the rudder ventilated and then wanted to broach,” said Ralph. “Its such a high-aspect foil that it goes from full lift to full stall in a snap.” Her hull structure is rugged, reliable traditional solid fiberglass to the waterline and balsa cored above. One judge deemed it “a privilege to sail on such a boat.”

But of all the full-size cruisers we sailed, the one that the judges felt would make the best all-around passagemaker for a performance-oriented couple was the Aerodyne 47. Her hull is designed by shorthanded-raceboat guru Rodger Martin, but the 47s slippery form is put to cruising use. “Shes a detuned thoroughbred,” said Ralph. “She has a shoal draft [six feet] and a small rig, yet shes real efficient going through the water.” The design brief was to create a low-energy boat, with sail area kept under 1,000 square feet. Shes built of E-glass and epoxy over a foam core. “The structural approach was superb,” said Ralph. “Epoxy is the best resin you can build boats out of, and all the signs were of high fiber-to-resin ratios.” The layout above deck and below is elegantly simple. “It was hard to wipe the smile off my face when I was moving around that boat. I felt comfortable going anywhere at a fast clip,” said Carol. “Down below, there are good sea rails everywhere, and sea berths with lee cloths on every one.” Skip said it had the best workshop and pantry.

The last comment in Skips notes sums up the judges feelings about the Aerodyne: “Wow! I like this boat.”

She takes the 2003 prize for Best Full-Size Cruiser.

Best Cruising Multihull: Voyage 580

The multihulls we sailed–all nine this year were catamarans–can be grouped according to whether theyre designed exclusively for owners or whether their creators kept an eye on the charter trade.

One boat, the 35-foot ClipperCat, stood out as the only multihull in the contest with an open bridgedeck. Though her composite construction (post-cured epoxy and Core-cell foam) is as modern as it gets, her lines echo James Wharrams vision of ancient Polynesian craft: hulls with low freeboard yet pronounced sheer in the bows. Accommodations with separate access are in each of the hulls; the cockpit is in the bridgedeck between the hulls, open but for a bimini. Twin Honda 9.9-horsepower outboards push the boat at just over 7 knots with little vibration. Under sail in 10 to 12 knots, she turned out speeds in the mid 5s hard on the wind and in the mid 7s when we cracked off to a beam reach. “I could see this as a great workboat,” said Carol, “maybe taking groups of kids out for sail training.”

Of the others, we sailed four more conventional cats that are oriented toward private ownership, cruising boats for a couple or family: the Broadblue Prestige 38, the PDQ 42 Antares, the Island Catamaran 48, and the Switch 51. Of these, the Prestige delivered the most comfortable handling; the PDQ, the best accommodations; and the Switch, the best flat-out performance.

Broadblue is a new British-based company that rose up from the ashes of Prout, whose demise last year marked the end of the worlds longest-running production multihull builder. The new Prestige 38 we sailed was taken from the molds of the Prout 38 that was introduced in 1998, and she retains that lines signature headsail-dominated rig. “Its described as a two-handed bluewater boat for owners, not charter, and I think they accomplished that,” said Skip. Unlike many cats whose hulls forward are spanned by netting, the Prestiges bridgedeck extends forward of the cabin house. “Hers is a resin-rich laminate, and her interior takes the cover-it-all approach,” said Ralph. “But she doesnt creak, and thats probably a cost-effective choice.” Carol said, “I like the maneuverability on the foredeck,” although she found the side decks and cabin top less easy to walk on. Of the folding companionway door, Carol said, “It felt like something I wouldnt want to be banging into or relying on.” The Prestige ran smoothly under the power of twin 30-horsepower Volvos, without vibration. And despite his skepticism about sailing with such a small main, Skip said, “I was really kind of impressed with how it sailed.”

Of all the owners-oriented cats we sailed, the one that would make the best waterborne home is the PDQ 42 Antares. “She was built right,” said Ralph, “with 0/90 1808 E-glass, six-pound-density Core-cell foam, everything bagged in.” Skip gave the systems high marks: “The electrical system was as good as anything weve seen. Beautiful, beautiful fusing.” Powered by twin 27-horsepower Westerbekes with conventional prop shafts, she was among the noisiest boats in the fleet, with readings of 97 decibels in the aft cabins. In terms of design, she had the highest freeboard of the cats we sailed, trading the advantages of cabin volume for the disadvantages of windage. Interior furniture is built of honeycomb-core panels, which, according to PDQ, saves 1,600 to 1,800 pound compared with plywood. And the team at PDQ really knows how to work with cored panels. “I really liked the woodworking,” said Carol.

The Island Catamaran 48 is the child of a yard formed in 1998 in Charleston, South Carolina. The boats design aim is to be a performance cat with luxury accommodations. Close-reaching in 8- to 10-knot conditions, we saw average speeds in the mid 6s and top speeds in the mid 7s. Powering at 9 knots, we measured noise between 91 decibels in the saloon to 95 decibels in the hulls. About the boats speed, Ralph surmised that “this is a threshold boat. She didnt perform outstandingly in light airs, but somewhere around 10 knots, she broke through the breeze barrier.”

The boat we sailed with the speediest performance numbers was the French-built Switch 51. She’s a boat with clear antecedents among Gallic multihull makers. Built by Sud Composites, a yard that built Catana 401s under contract, the Switch was drawn by Van Peteghem & Lauriot Prévost, designers of the Lagoons. Her lines are defined by a high bridgedeck for wave clearance and a low coachroof for windward performance. In 10 to 11 knots of breeze, we sailed 7.3 knots at 60 degrees apparent.

The remaining four cats are designed with the charter market clearly in mind.

Among these, we sailed two 40-footers: the Fountaine Pajot Lavezzi 40 and the Island Spirit 40.

The Fountaine Pajot Lavezzi 40 is the latest model from the worlds most prolific builder of multihulls. (FPs staff of 420 employees builds roughly 150 boats per year.) Her hulls are injection-molded composite structures of isophthalic resin and glass over a closed-cell foam core, with a vinylester skin coat to prevent osmosis. Her layout features a galley in the bridgedeck saloon positioned at the aft end of the cabin house; a sliding glass door opens the galley to the cockpit. Shes a quiet boat, with noise readings between 64 and 72 decibels as twin Yanmar Saildrives pushed us at 8 knots. Under sail in 10 to 12 knots, we close-reached between 7.4 and 7.7 knots.

The Island Spirit 40 comes from the South African yard of Fortuna Yachts, which is affiliated with Trade Wind charters. Its galley arrangement is similar to the Lavezzis. Her performance is similar, too, with noise readings between 67 decibels and 75 decibels; in 8 knots of wind, she beam-reached at 4.5 knots.

Moving toward the upper end of boats that a typical doublehanded crew could expect to sail comfortably is the Lagoon 470. Despite the name it shares with the 470 that was introduced in 1998, the new Lagoon truly is new. Changes include a one-foot-three-inch increase in hull length, a two-foot increase in waterline length, increased bridgedeck clearance, and lengthened keels. The judges were impressed. Said Skip, “Its got big, strong gussets to support the rudder, the batteries are tied down beautifully, the gensets housed in a box, and the sound test was superb: 63 decibels in the saloon.” All around, the Lagoon got high marks from the judges.

But the boat that takes the multihull prize is the Voyage 580. “This was the builder that won last year, and with this boat, theyve done it bigger and better,” said Ralph. He cited the quality of glasswork and stainless-steel work. “The Voyage is just a boat thats a pleasure to be on in so many ways,” said Carol. “All the lines that led aft were great. In looking at multihulls, every time I see a mainsheet led through a rope clutch, I get nervous. This boat has a dedicated winch, no rope clutch, and it was right at the helm, which was great.”

Skip pointed out details that spoke to the care with which the builder executed the boat. “On the deck hatches, they have massive gaskets and big latches; theres no water in them.” He described his overall impressions of the boat as fast, smooth, and quiet.

“All in all, for $800,000 you should get one hell of a vessel, and it is,” said Ralph.

Special Awards

Best value: Of all the 30 boats we sailed, the boat the judges deemed to represent the best value for a cruising couple is the Broadblue Prestige 38.

Ralph summed up their assessment: “She’s got an easy deck to get around, she’s got great visibility, and she’s got watertight bulkheads.” Most of all, when we look at her price-per-displacement ratio of $14.52 in the context of her peers, she provides the space of a catamaran, a rig that’s truly manageable for a wide spectrum of doublehanded crews, and a price point that’s accessible. “This is a husband-and-wife boat with the capability to take along another couple or two or three kids,” said Ralph.

Most Innovative: Two boats–the ClipperCat and the Etap 32s–vied for this years innovation award. The judges loved the way getting rid of the cabin house opened the ClipperCats cockpit, putting the sailor back into the world of wind and water. But in the final analysis, the Etap trumped it with not one but three innovations: its unsinkability, its tandem keel, and its vertical steering system. “A lot of thought went into that boat,” said Ralph.

Overall Cruising Boat of the Year: The big question, of course, comes down to which boat, drawn from among the category winners, would take the overall award. After 10 days of sea trials and dockside inspections, the choice came down to two very different boats: the Aerodyne 47 or the Hallberg-Rassy 43.

“This is a real apples-and-oranges thing,” said Carol. “Theyre both excellent, excellent boats, and one of the joys of sailing each of these boats was the ease of movement on deck. But on the Hallberg-Rassy, everything seemed so logical to me: where it was placed, where my movement would go. If I were going to take a boat anywhere around the world, and I mean anywhere, for me it would be the Hallberg-Rassy.”

Ultimately, after lengthy deliberations, it was Carols argument that carried the day. Congratulations to all of the folks who put together the Hallberg-Rassy 43, the 2003 Cruising World Boat of the Year.

Tim Murphy, CWs executive editor, directs the magazines Boat of the Year program. Special thanks go out to Kathy Gregory and Tom Neale, who coordinated the event, and to the folks at Ribcraft (www.ribcraftusa.com), who provided smooth, fast rides to our appointments with the boats. Comprehensive reviews of many of the boats featured here will appear in CW throughout the year.