Of a small sailing craft, E. B. White wrote, “It is without question the most compact and ingenious arrangement for living ever devised by the restless mind of man-a home that is stable without being stationary, shaped less like a box than a fish or a girl, and in which a homeowner can remove his daily affairs as far from shore as he has the nerve to. Closehauled or running free-parlor, bedroom, and bath, suspended and alive.”

The restless minds behind the Outbound 44 belong to Phil Lambert and Craig Chamberlain, founders of Outbound Yachts.

In Annapolis, Maryland, last October I said to Phil, “There are so many cruising designs already available to choose from; why go back to the drawing board?”

He told me he came from a racing background. “I was convinced we could develop a boat with the capacity required for serious cruising, with sufficient comfort to encourage living aboard, and with the added safety that comes with performance and handling,” he said. “But too often, that quest for performance led me to vessels that were too exotic, expensive, and uncomfortable. I wanted a solid-glass hull-heavy, yes, but safe, and well suited for hard offshore work. I felt we could still achieve high performance through sophisticated shape, a powerful rig, and by keeping the weight well away from the ends.”

Phil admits that his choice of designer, Carl Schumacher, who was known for squeezing every last ounce out of his creations, was at first reluctant when approached with these design parameters. After reviewing Chamberlain’s original drawings and lengthy discussion, however, Carl felt challenged to find that coveted speed without compromising hull integrity or the seakindliness that can only come from displacement.

And rise to that challenge he did, for one of the last designs to come off Schumacher’s board before his death in early 2002, is an elegant blend of sensibility and sophistication. For a slippery underbody, he combined long waterline length (40 feet 3 inches) with moderate beam (13 feet 6 inches). This is steered with a high-aspect spade rudder with a standard 4-inch stainless-steel rudderstock, or a carbon-fiber upgrade. For power, he balanced a high-aspect solent rig of 1,151 square feet with the righting moment of a 6-foot-6-inch, 10,000-pound encapsulated bulb keel.

To convert concept into craft, Lambert sought a yard capable of constructing vessels of consistently high quality yet at an affordable price. In 1999, he chose Hampton Yacht Building Company of Shanghai, China. While no one disputes that the quality-to-cost ratio of Chinese craftsmen represents good value, Phil concedes that public perception of Chinese yards may yet be tainted by the irregular quality control from the industry’s nascent years.

Still, he says, “The Chinese industry has matured. They now recognize that to remain competitive, they must establish rigid standards. To further ensure absolute consistency, we decided to source the entire boat from the United States.

The hull is built of hand-laid fiberglass, reinforced with brawny stringers, longitudinals, and bulkheads bonded to the hull while in the mold. High-stress points receive additional laminates. Knytex biaxial fiberglass enhances impact resistance, but attentive to the potential dangers of an increasingly littered ocean, a watertight crash bulkhead is added 7 feet aft of the stem. This laudable safety feature doubles as a sealed and spacious locker to hold sails and rodes. Outer layers of vinyl-ester resin keep blisters at bay, while Valspar ISO-NGP gelcoat ensures long luster.

The decks are Baltek balsa cored for stiffness. The hull/ deck joint is bonded with 3M’s indestructible 5200, then mechanically fastened with stainless-steel through-bolts centered every 4 inches. The two structures are still further fused by adhesion to interior bulkheads perimeters.

No area of the vessel is more central to safety, comfort, and convenience than the cockpit. The Outbound’s aft cockpit is enormous yet won’t wallow under the weight of boarding seas, for it’s self-bailing aft through a wide, open-ended sole. Still, the companionway is protected from flooding by a 9-inch bridge-deck and two forward scuppers.

The cockpit sole extends out onto the swim platform via a box containing the life raft. This allows deployment and entry from the safest part of the boat without exposure to swinging booms or boarding seas and doesn’t require the cumbersome raft to be hefted over high lifelines, as in deck-mounted rafts.

The main hatch slides smoothly and is tight. But it could use a two-way latch to firmly secure it yet allow access from above or below. The companionway is well protected by swinging doors backed up by three Lexan washboards securely slid into parallel grooves.

Ergonomically designed with high, comfortable backrests, the cockpit seats are long and wide enough to sleep on yet aren’t so far apart as to allow bodies to be dangerously pitched across. Manual bilge pumps are located strategically at both the helm and the navigation station below.

Ironically, one of the Outbound’s best ideas may also be the worst. The port cockpit seat opens up to a massive stowage locker and workbench below. With the locker lid up, even the tallest person can stand up straight over a spacious workbench with a vice and all tools readily at hand. The workspace becomes well lit and cool, while isolating noise and dirt from the cabin interior. Bravo-but such a large opening exposes the interior bilge to flooding. It therefore should be gasketed, not just guttered, and all hinges and latches need to be thumb-thick and fastened with backing plates. These are quick and affordable fixes; I note them only because there were so few other faults to report.

Movement forward on deck is free-flowing yet made safe with ample handholds, well-fastened rails, stern rails that extend past the vulnerable point of exit from the cockpit to the side deck, mast pulpits, and aggressive nonskid. Stanchions, an exceptional 30 inches high, hold twin vinyl-coated lifelines.

The twin anchor rollers extend far enough outboard to protect the stem from anchor damage but are wisely supported with the headstay and a short bobstay. A clever catch tray with a drain helps keep anchor muck off the foredeck. Ground tackle was deployed and retrieved smoothly via a Lewmar Ocean 3 windlass.

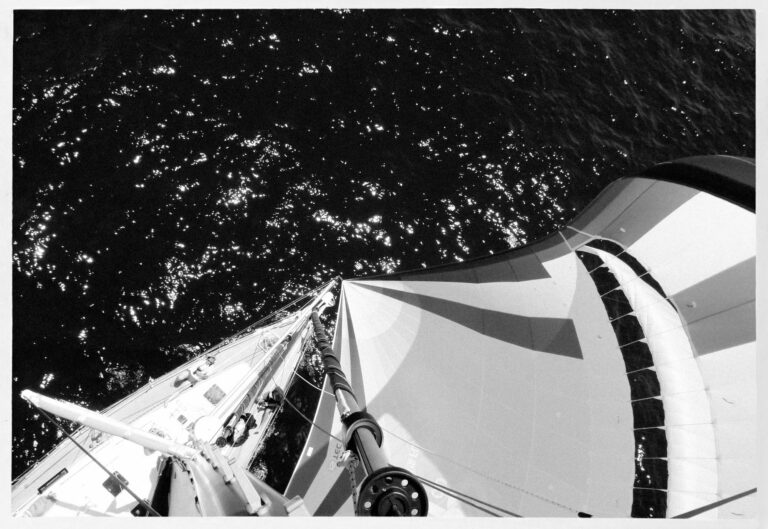

A keel-stepped Charleston spar with moderately swept double spreaders comes standard, with a separate trysail track already installed. Outbound has chosen the increasingly popular solent configuration, with a Harken-furled 140-percent Hood genoa and a hanked Hood 75-percent jib on a removable inner stay. This is a versatile cruising setup that also provides a long run of foredeck space for dinghy stowage.

For all its lush allure and flawless finish, the interior reflects the sound philosophy of allowing form to follow function. A slight rise in the main cabin creates a bright and airy feel without breaking the sole into tiers. Ample handholds and bulkheads make moving about in a seaway secure.

A single head stands to starboard of the companionway steps, where it enjoys maximum ventilation and doubles as a wet locker. A snug but complete forward-facing navigation station nestles to port.

The well-appointed U-shaped galley is spacious without being dangerously open. All surfaces, including the Corian countertops, are deeply fiddled. Foot-operated pumps wisely back up the twin sink electrical pumps.

A large saloon table sits across from a starboard settee. These seating surfaces convert into four practical sea berths aft of the mast. A private double berth lies aft to starboard, and the workshop/stowage area is aft to port.

An elegant owner’s cabin is situated forward, and in the case of Ginger (hull number 10), it included a slick computer/office station in lieu of a second head. Commodious stowage is found throughout.

The sole is teak and holly, and all boards lock down. The well-limbered bilges are gelcoated for cleanliness and drain into an 18-inch sump, a valuable feature lost in many modern designs. Range-extending tanks carrying 160 gallons of fuel and 200 gallons of water sit low and central in the bilge, minimizing hobbyhorsing and freeing stowage space beneath the settees.

The cleanly installed 75-horsepower Yanmar is accessed under a pneumatically lifted companionway ladder and from two side panels. The one Group 27 and three 8D batteries (with room for more) are well secured.

The six-page equipment list accompanying the Outbound 44 is complete down to the safety flares, making this a genuine turnkey package. Mel and Barbara Collins, the satisfied owners of Ginger, put it best: “They provide strong leadership, and they don’t nickel-and-dime you.” The Outbound team has clearly discovered the word custom within the word customer, for they happily accommodate wide divergences from the original design and welcome the owner’s participation in the process. To best express this, they’ve included in the sale price a trip to the boatyard in China at any phase of construction.

While a good gale would’ve more properly assessed seakeeping characteristics, the 14-knot autumn breeze offered on the day of our testing was appropriate for addressing heavy-displacement/light-air performance concerns. With full main and genoa, we held 6 knots on a broad reach, 7.5 on the beam, and a solid 8 knots respectably close to weather. The boat stood up stiffly, answered its helm with precision, and balanced well. With a hanked jib, furling genoa, and a fully battened main with lazy jacks, the raises and strikes were effortless.

E. B. White concluded his description of a small sailing craft with this thought: “It is not only beautiful; it is seductive and full of strange promise and a hint of trouble.” The Outbound 44 is indeed beautiful and seductive. Because of its genuine bluewater readiness, it’s also full of strange promise. But, alas, because of its thoughtful design and meticulous execution, any new owners will have to provide their own hint of trouble.

Alvah Simon, author of North to the Night ($15; 1999; Random House), has lived for two years in Whangarei, New Zealand, with his wife, Diana.