AIS tool

Hanging out in the U.S. Virgin Islands, I was doing some last-minute provisioning on St. Thomas when I glanced at my trusty iPad to check my to-do list. The web browser happened to be open, and I frowned as I glanced at it and rechecked the lat/long being displayed. Damn! I swiped into my Skype app and soon had my wife, Carolyn, staring back at me from our ketch, Ganesh, anchored off St. John.

“You’re dragging!” I said.

“I am?” she asked.

She was sitting below at our nav table, and now she brought her iPad up into the bright cockpit with her. “No,” she said, slowly panning the harbor with the built-in video camera for my benefit. “I don’t think so. The wind just went a tad light and shifted to the south as a small line squall came through a few moments ago. We didn’t drag. We just swung on our generous scope. We’re maybe 100 feet from where we were when you dinghied ashore, Fatty. Hey, incidentally, did you buy the coconut water and bananas?”

Whoa. Let’s back up and get an overview of what’s happening here.

The common denominator running through my watery life isn’t sailing. It’s freedom, and I aspire to be the freest man on this planet. But in addition to worshipping freedom, I adore technology. In fact, without modern shipboard electronics, I would be far, far less free. My Pactor modem, for instance, allows me to send off, via SSB radio, my stories from even the deepest, most remote corners of the seven seas. I earn my living, and have for decades, thanks to technology. Having something so dreary and static as a physical address is so yesterday, in my humble opinion.

Which brings us to the subject of the Automatic Identification System.

What is AIS? Basically, it uses a tiny little box with a two-way VHF radio, and interfaced GPS within, that broadcasts my boat’s position and receives the same sort of information from nearby vessels. Depending on the technology employed, the device can even tell me which boats I need to worry about hitting and which I can ignore. This almost eliminates offshore collisions between AIS-equipped vessels, which is surely laudable.

Major ports and a growing number of ships have these Class A units continuously broadcasting and linked to various sites on the Internet. Even better, a Class B AIS, for recreational vessels, is relatively inexpensive (it costs less than $1,000), small, highly dependable, and draws little electricity.

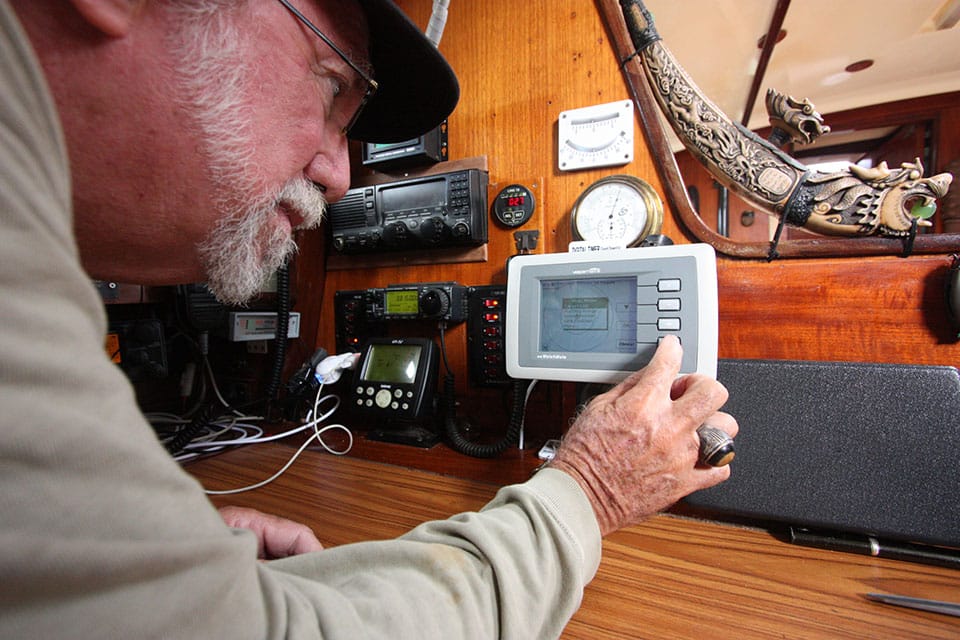

If I had to toss overboard either my Vesper Marine AIS Watchmate 850 (www.vespermarine.com) or my radar, well, bye-bye radar. AIS is the single most important anti-collision tool invented in my lifetime, which is way cool, right?

There is, of course, a catch: Evolving technology often encroaches on personal privacy in unexpected, and undesirable, ways.

Here’s the astounding reality of my vagabond, seemingly off-the-grid life: If I’m cruising in the Virgin Islands or transiting the Panama Canal or anchored in many of the larger, busier ports in the world, all you have to do to find me is go to www.marinetraffic.com and search for “Ganesh/Capn Fatty.” Within seconds, you have my precise, up-to-the-minute location. If I happen to be in deep ocean and beyond VHF-radio range of shore, then go to shiptrak.org and punch in my ham call sign, W2FAT, for a slightly less real-time position.

I find this MarineTraffic site extraordinary. It’s available for free to anyone with a computer. People can browse the website, and, if my AIS transponder is on and I’m within VHF range of a shore receiver, they’ll see my course and speed and even a picture or two of my boat! The AIS position isn’t approximate, either. It’s exact. A drone sent from Langley, Virginia, could sink me at any moment.

Is my vessel dragging while it’s anchored in the Virgin Islands? If so, I can tell instantly from any cyber-connected computer in the world.

The implications are fathomless.

This has eliminated one major problem of buddy boating, because you can easily determine each other’s position if you become separated. It used to be that we buddy-boaters would prearrange a primary rendezvous and a backup rendezvous point, monitor a certain VHF channel, and tune into the same SSB nets. Now we just check our AIS units or go online.

Perfect, eh? Well, no. This, too, has some unanticipated drawbacks.

It used to be that I could drop a white lie to an editor if I missed a deadline. That was when I snail-mailed my stories from the Virgin Islands.

“Whaddaya mean you ain’t got it, chief? Damn, it’s probably stuck in a container on Puerto Rico! Let’s give it a few more days. It should turn up.”

| |_**AIS is a valuable tool that can help eliminate surprises, but a prudent skipper will make sure that he or she has other navigation aids at hand and that the boat’s ready for whatever Mother Ocean dishes out. Click here for tips on preparing a boat for voyaging. **_|

Not any more. Now editors email me for rewrites in the middle of a gale! And they want the finished copy the next day or sooner, regardless of whether I survive the blow or not. There’s no place left to hide. Connectivity is a two-way street. Woe is me!

But wait—it gets worse. I’m a fairly talkative guy, and I like to keep in touch as I sail the world. Often I do this with Facebook posts. This makes it doubly hard to ask for a pay raise from my desk-bound editors in freeway-clogged America, especially when they see the hourly posts with photos of me and my blessed betel-nut buddies hanging out in Micronesia.

Busted!

Yes, as I said, my vessel is geotagged 24/7 while in a major port, and so am I as I zip around the harbor in my dinghy with my iPad. Example: The last time I stole some Internet time at the McDonald’s in Simpson Bay, on Sint Maarten, I discovered that two of my old friends were sipping brewskis at the yacht club by the bridge and a third sailing mate of mine was one more block away, at Burger King! Zooming out on Google Earth, I could even see how many of my French sailing pals were anchored in Marigot.

Of course, both my iPad and my AIS have off switches. I can, if I so choose, go into stealth mode. I might do this sometimes, if, for instance, I want to murder someone or smuggle some out-of-date cartons of UHT milk into America.

But shutting off the AIS or my iPad’s geotagging seems a little sneaky. And I have nothing to hide. So I leave them on and watch with fascination where this weirdly morphing technology unexpectedly leads.

Is social media really bringing us together or just cyber-drugging us into meekly accepting our increasing loneliness? I dunno. I’ll pose the question on my Facebook Timeline and get back to you.

Many cruisers, of course, don’t indulge. Lin Pardey once told me that sailors with onboard Internet connections have “missed the plot,” meaning, I think, that the whole joy of getting away from it all is negated if you have somehow managed to digitize your previous reality and bring it with you.

She has a point. On at least one occasion, I’ve been in total bliss far offshore and had an angry email bring me crashing down.

With technology, you have to take the bitter with the sweet. Search-and-Rescue craft can find my vessel almost instantly. But, so, too, can disgruntled book readers who want their money back. Friends can find Ganesh as well as thieves. Ditto for angry husbands, bill collectors, stowaways, repo men, and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Have you ever snuck into a country without clearing in? Or pulled the, ahem, familiar trick of clearing into both Turkey and Greece at the same time to avoid repeated customs and immigration hassles?

Of course I always clear into the British Virgin Islands when visiting from the U.S. Virgin Islands—although perhaps there’ve been a few informal stops to see Ivan and Foxy on Jost Van Dyke.

But can you risk such visits today, when any Facebook fan or guy with an AIS receiver or computer knows exactly where you are every second and where you—you naughty boy—have been?

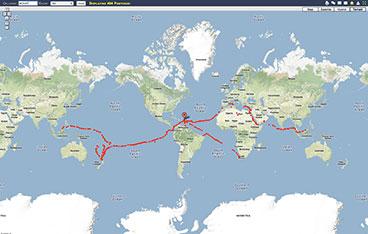

| |At sea, far from any robust wireless connection, Fatty and Carolyn can still be tracked, thanks to their SSB and Pactor modem. Want to follow their route? Log on to www.shiptrak.org and enter their ham-radio call sign, W2FAT. Our cyberworld is out of balance. I once had a shipwrecked yachtie from Oz complain to me about how long the New Zealand helicopters took to arrive after he set off his EPIRB|

I dread the day when a foreign customs and immigration official asks, “And do you want to stick with that flimsy story, Fatty?” as he tilts his computer screen to show me _Ganesh_’s stop-and-go inbound track on [MarineTraffic.com](http://www.MarineTraffic.com), visually disproving everything to which I just breezily testified.

The days of the Artful Dodger are over, smothered by our modern need to be in touch with ourselves, friends, family, fans, customers, and, of course, our physical possessions. My iPad, by the way, automatically IDs itself on the Internet if it’s apple-picked by a thief.

It gets even weirder. Have you heard of trainspotters? Well, a few sailors and coastal residents are getting into the same eccentric thing with ships and yachts. They take snapshots of the vessels they see passing by with geotagged cameras and identify them using AIS.

Then they post the pics on the Internet. It’s a hobby, I guess. This is how all those blurry photos of too-distant ships got uploaded to MarineTraffic.

Strange, eh? Well, consider this: Are there Somali pirates smart enough to visit MarineTraffic.com or Shiptrak.org? I think some are, and I don’t want to meet them.

On the other hand, I was just anchored in the Virgin Islands’ Pillsbury Sound and wanted to know who owns the megayacht Rising Sun, upon which Oprah and Bruce Springsteen were seen cavorting on deck. It belongs to David Geffen, according to cyberspace.

Yes, our cyberworld is out of balance. I once had a shipwrecked yachtie from Oz complain to me about how long the New Zealand helicopters took to arrive after he set off his EPIRB. This, on the same planet where police response time in East Los Angeles is measured in weeks, if at all.

I’ve elected to have an AIS aboard. However, most large ships are required to. And certain locations, such as Singapore, are starting to demand them aboard yachts, so they can be called upon in an emergency. Maybe that’s a good idea, maybe not. I, for one, wouldn’t want to cruise a corrupt country’s coast with my AIS blaring my position to every on-the-take governmental official within a 50-mile radius.

On the other hand, the authorities can use the technology to our benefit, with things like virtual buoys. With the flip of a switch, they can place a temporary AIS nav mark (remotely, with the AIS transmitter ashore, not on site) to warn of, say, a sunken freighter or a pod of whales. That’s a good thing, in the hands of a benign, well-regulated coast guard. However, AIS is also a shipwrecker’s dream. When will the first supertanker get hacked into danger through overreliance on its techno toys?

These are serious, complicated, and sophisticated navigational issues. I’m just a poor sailor boy, struggling to make techno sense of it all. Sadly, I’m not smart enough to provide many answers, but the question is glaringly obvious: Does owning an AIS make you more or less free?

The bottom line is that our world, both ashore and afloat, is changing rapidly. Technology will steadily advance whether we want it to or not. It’s up to us, as citizens and sailors, to use our technology, and not be used or abused by it.

In the meantime, if I’m busy on Facebook and don’t happen to notice that Ganesh is dragging, text me, OK?

As this issue goes to print, the Goodlanders have just set off on their third circumnavigation. Their current course and speed are just a click or two away.