If I’ve learned one thing, it’s that you should never say never. Like the owner of the boat named My Last Boat XIV, I made the mistake of thinking that my 2005 cruise in the Bahamas aboard Mana, a Morgan 382, was going to be my last sailing voyage after cruising more or less full-time for the previous 35 years. I had decided then that it was time to visit countries inland, rather than just seeing them from anchorages in ports and harbors. Two years ago, a tragic event proved me wrong. My very good friend Klaus Freienstein had died of a heart attack while sailing aboard his son’s boat on the Baltic. Time passed and shock was progressively replaced by gentle sadness. Lilo, his wife, had put up his boat, a Saltram 36 named Swantje, for sale. This was a fine cruising vessel aboard which Lilo and Klaus had sailed over the years from Germany throughout the United States and the Caribbean. The Alan Pape design is a traditional, heavy-displacement cutter derived from Colin Archer lines. Swantje was indeed a go-anywhere vessel — very strong and outfitted for any ocean. The problem was that Swantje had been left afloat in Andrés, near Boca Chica, a few miles east of Santo Domingo on the south coast of the Dominican Republic, and Lilo had received absolutely no offer for her. In despair, she asked me to move her boat to a better market in the U.S. Initially, I refused, thinking that my sailing career was over — I had not sailed for years — but I finally accepted.

In early November, I flew down from Canada with my Thai wife, Pim, who had never even seen a sailboat before. Upon my arrival, I soon realized that Swantje had been seriously neglected and pilfered. She was in a pitiful condition because those who were in charge of her upkeep thought the boat had been abandoned by her owner.

Most of the electronics were either gone or not functional. The inflatable dinghy’s fabric had completely dried out under the intense Caribbean sun. There was no toilet. The cooking stove, a kerosene Taylor, was unrepairable. An anchor had been stolen. The fridge did not work. Most important, the packing gland, a no-drip type, was leaking badly because the shaft had been bent during one of two hurricanes that had hit that coast.

I was discouraged. Most tools had disappeared. All my attempts to get an explanation for such a state of affairs were met with blank looks. So I set out to try to fix crucial issues such as water coming into the boat and repairing the bilge pump. The cabin was covered with mold, and most systems — watermaker, seacocks, winches, self-steering vane and autopilot — were frozen solid with corrosion and salt. Fortunately, the sails were in good condition and the rigging terminals appeared healthy.

The month we spent trying to fix things was extremely frustrating. Pim and I ordered some equipment that was then stolen from the post office. On the beach nearby, gunshots were heard every night. “Never go to the beach after sundown,” we were warned.

Trying to get official papers from customs and immigration turned out to be a nightmare, so much so that we envisaged leaving the country secretly at night. Corruption here seemed to be an inescapable way of life. All was not bad, however. I’d made a Dominican friend, Tony Torres, who was kind enough to help us and, fortunately, was a small enough guy to squeeze himself into the engine compartment to replace the packing gland. And there was also Olé, the tiny kitten left to die in the harsh sun in the marina parking lot.

We took Olé aboard so he could pass peacefully. His eyes were stuck shut, and he was smaller than a tiny bird. We fed and cared for him, and day by day, he slowly came back to life. Seeing that nobody at the marina wanted a cat, we were forced to take him along on our trip.

So in early December, we decided to cast off, even though we had outdated charts and no GPS, toilet, stove or dinghy. Lilo and I had spent too much time and money to turn back and abandon Swantje.

Huge swells met us as we left the harbor, and I was a little apprehensive, having left my sea legs at home many years ago. We motorsailed all night along the southern coast and anchored at the southeastern tip of Hispaniola with serious fuel and engine-coolant leaks.

In Isla Saona, we spent two days at anchor repairing the leaks, enjoying the scenery and resting after a demanding first night at sea aboard an untested boat. Then a fresh breeze built up from the east, and we left at sundown to negotiate the infamous Mona Passage. We tacked our way north all night, hugging the coast so as to follow a relatively safe but narrow passage through “the hourglass,” a deep channel between shoals on both sides.

A few miles offshore of the entrance to Samaná Bay, we radioed a French friend we had met at Marina Zar Par, where we had picked up Swantje, to inform him that since it was nighttime and we had no detailed charts, we would not meet with him in Samaná harbor like we had planned. We found out much later, upon our arrival in Florida, that our friends never received our message because our VHF was not working. Two days after our planned date, our friend, Claude Bosc, called the Dominican Coast Guard as well as the Canadian Embassy to start a search-and-rescue operation.

Meanwhile, the fresh breeze turned into a gale. The spectacle was awesome, and Swantje behaved beautifully — we even reached 13.9 knots on the knotmeter surfing down a particularly steep wave. I had also managed to repair the autopilot. It had been designed to be affixed to the port side but was installed on the starboard-side. So, everything it did was 180 degrees off. Seeing that, I inverted two wires and the pilot worked perfectly.

During all that time, Pim settled in, and even though she was new to sailing, she kept a good watch on ships and Olé. The dying kitten was by now fully alive, playful and developing his sea legs far more quickly than his human friends.

Reaching the western end of Hispaniola, we had several routing choices. We could keep going in the sea lanes through the Old Bahama Channel toward Florida; we could go through the Bahamas — Great Inagua, then through Cat Island and the northern Exumas; or we could cross the rock-and-shallow-ridden Great Bahama Bank to the States. Since we had no instruments, we decided that sailing during the day among rocks was safer than sailing at night in sea lanes. Shoals did not, per se, represent a great problem in terms of safety.

We were 5 to 6 miles south of Great Inagua and could see the glow of lights on the horizon. And then the wind died. We were sailing mostly by dead reckoning, but here currents change direction with the tides. We were becalmed and had to figure out a way to guess our drift in the currents. The engine was not an option since we were low on fuel.

In the morning, we saw the rock at Columbus Bank, which lies to the southeast of Ragged Island, and that gave us a precise fix from which we could derive an accurate course to follow between rocks. We lucked out with a good beam reach and some fishing success. So we kept on sailing in a fair breeze.

Swantje , an Alan Pape-designed Saltram 36, certainly looks salty, albeit a little tired. Indeed, it’s a true go-anywhere boat, and with the rugged construction, canoe stern and full keel, it was built more for seaworthiness than for creature comforts.

We then turned north, where there were no rocks and no shoals to worry about, and then exited the Banks and set out to cross the Gulf Stream. With absolutely no charts of the U.S. coast, except for very large-scale ones, I guessed that the approximate location of our landfall would be Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

Indeed it was. Welcome to mega-yacht paradise. Coming from a desperate nation such as the Dominican Republic, this was a violent contrast. I had sailed into Fort Lauderdale several times before, but never realized how big — monstrously big — it had become.

We motored along the waterway, with no chart. The real problem, however, turned out to be our lack of radio, or indeed even a horn. Bridge operators could not be called in advance for bridge openings, and several times we sat there, in neutral, waiting for the attendant to understand what we wanted.

In Vero Beach, we unexpectedly met with our dear friends Louise Gervais and Richard Dubé, and they informed us that the Dominican Coast Guard had been looking for us somewhere north of Hispaniola and called off the search after a few days. We made a phone call to authorities and straightened it all out. Olé was now a fully developing kitten, eager to walk ashore and meet new people. We finally gave him up for adoption.

A few days later, we arrived in Cape Canaveral, Florida, and hauled out Swantje. We prepared her for sale and flew back home to continue my “retirement” from voyaging.

Thoughts on Seamanship

For more than 30 years, I had written about safety while cruising. This trip was a high-risk adventure, which should never have been undertaken. We decided to sail anyway because of pressures from everywhere, including the money already spent by us and Lilo. We felt we had no choice — after so many days of exhausting efforts to make Swantje sailable, we felt we could not turn back. Serious mistake. No professional delivery captain would have done this trip, for obvious reasons.

If anything had gone really wrong — dismasting, engine failure, accident — we could not have radioed for help, we could not have survived in the dinghy or life raft, and we didn’t even have sufficient tools for serious repairs. We had only one anchor, outdated charts and no GPS.

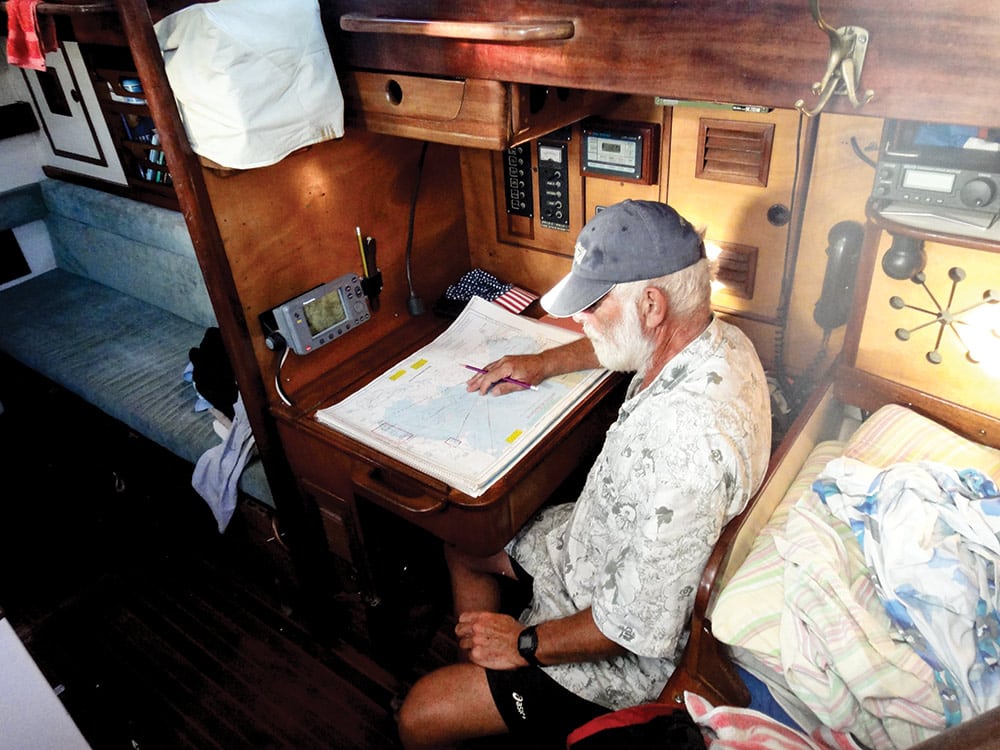

I know, I know. When I started sailing, I had no GPS either and sailed mostly by dead reckoning, radio-direction finder and a sextant. Still, this was a dangerous voyage done in a hazardous area, and I should have insisted on having a good GPS. However, Lilo, the owner, had spent all she could for this trip, and I could not stretch her budget further.

Now if we look at this voyage from a different perspective, we realize that this is the kind of passage that numerous sailors did before the advent of GPS and fancy safety systems. In the 1960s and 1970s, dead reckoning, a good compass and a solid boat were all that was needed to accomplish a safe passage. How many sailors nowadays know the art of dead-reckoning navigation? How many can draw a fail-safe route — that is, a course that takes potential mistakes into consideration? How many would sail for 12 days without the luxury of a stove or the apparent security of a radio?

If this was my last sea voyage, I can say one thing: The cycle is now complete. My last voyage was nearly the same as my first one back in 1977. Although, like many, I have become reliant on fancy electronics over the years, on this trip, the old reflexes came back to the surface.