angelpony1.jpg

“Force 10, Beaufort Wind Scale: 48 to 55 knots, storm, very high waves with long overhanging crests. The resulting foam in great patches is blown in dense white streaks along the direction of the wind. On the whole, the surface takes a white appearance. The tumbling of the sea becomes heavy and shocklike. Visibility affected.”

–Reed’s Nautical Companion

Aboard the Hunter HC50 BreaknWind, visibility was compromised in a strange and wondrous way. So when owner John Moore pointed to a cloud in the night sky and declared incredulously, “Theres a star in the eye of the angel pony,” crew Phil Gouzoule knew that 48 hours at the helm was quite enough for his skipper. It was November 7, 2002, four days out of Newport, Rhode Island, and 90 miles west-northwest of Bermuda on the first leg of the third annual North Atlantic Rally to the Caribbean (NARC) from Newport to St. Martin. During the previous two days, the wind had gusted over 60 knots in a white squall that lifted Gouzoule off his feet and dropped him on the binnacle, the seas had built to 25 feet, green water had gotten below, and Moore and Gouzoule, whod shared the watch over much of that stretch, were exhausted.

At 2030 on November 6, 280 miles east of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, and 300 miles northwest of Bermuda, the crew on Babe, a Swan 46 skippered by Captain A.J. Smith, dropped her triple-reefed main and ran under bare poles in sustained 50-plus-knot south-southeast winds, with numerous gusts well over 60, and indulged in some fine cuisine while the storm raged. Babe was part of the NARCs self-dubbed Chicken Fleet that sailed way to the west of the rhumb line, not only to enter the Gulf Stream at a narrow point but also to buy time while an intensifying low-pressure system passed to its east. Although there was no way Babe could have avoided this massive low, which stretched from Hatteras to Newfoundland, her skippers conservative decisions made for a relatively pleasant passage to Bermuda with no storm-related damage.

In the wee hours of November 7, about 60

miles northwest of Bermuda, the Swan 48 Hinano, under the command of Captain Patrick Childress, was jogging along at seven knots under staysail in 20- to 25-foot waves, broad-

reaching in 40 to 50 knots of southerly wind. One of only two boats among 17 in the NARC fleet to shoot the rhumb line, Hinano had enjoyed a smooth Gulf Stream crossing, exploiting a 130-mile southeasterly meander, and an exhilarating passage. I was aboard Hinano, one of eight 43- to 53-foot Nautor Swans in charter service being delivered with professional captains and paying NARC crews from New England to their base in Anse Marcel, St. Martin, French West Indies. The remaining nine boats, ranging from a J/42 to a CT-72, were, like Break’nWind, privately owned and crewed. I knew it was crunch time, with no margin for error, yet our crew was loving it, shouting out each record wind gust as though it were a vital waypoint to be ticked off for all to hear.

Different ships, different long splices–but one fact remained constant: Four days into the NARC, smash-mouth rallying had returned to the North Atlantic for another year. Despite an ominous prestart forecast from weather router Susan Genett, portending winds gusting from 30 to 45 knots on three of the first five days–a prognosis that wouldve kept most veteran cruisers in port or convinced those already out there to head for home–17 boats and about seven dozen sailors chose to head out to sea and play the cards that were dealt them.

I first met the man who would organize the NARC rallies a decade ago in Porto Sherry Marina, just west of Cádiz, Spain, a gathering point for the America 500 rally fleet commemorating the 500th anniversary of Columbus’ voyage to San Salvador by way of Madeira and the Canary Islands. Near where I stood, bubbles rushed to the surface from beneath a European sloop named Double Malt. “What’s that?” I asked, pointing to the disturbance.

“That’s Hank Schmitt,” answered an America 500 participant. “He’s on Hunk-A-Schmitt,” he added, pointing to a Tayana 37 with Huntington, New York, as its hailing port. “He’s got scuba gear, and he’s checking Double Malt’s bottom.”

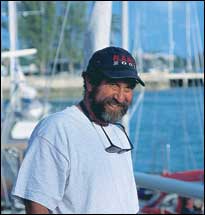

Schmitt, a former oil-rig worker/commercial fisherman/yacht manager–and the founder of Offshore Passage Opportunities (OPO), a crew-networking service/passagemaking club, in 1993 and of the NARC in 1999–raised capital to realize his 1992 transatlantic dream by selling everything he owned that wasn’t essential to his America 500 project, by holding benefits, and by offering berths to paying crew aboard Hunk-A-Schmitt.

When he needed publicity for his fund-raisers, a friend from a local transport company carried Hunk-A-Schmitt, draped with two Italian flags, on one of its trucks in Huntington’s 1991 Columbus Day parade. A woman dressed as Queen Isabella stood in the bow while five local college students marched in front with a banner proclaiming Hunk-A-Schmitt as “The Unofficial Entrant from Huntington, New York.”

“We handed out party invitations along the route,” said Hank. “Right after the parade, we stepped the mast, and by 4 o’clock we were docked at Coco’s Waterfront Restaurant to host a get-together the entire spectator crowd had been invited to.” Raising capital? No problem.

|

|

| |

|

|

| Hanks commitment to the rally didnt end there. He sailed Hunk-A-Schmitt singlehanded to Spain. One hundred miles southeast of Montauk Point, New York, he rendezvoused with the 81-foot longliner Catherine E, on whose decks hed once labored hard and long, to trade a six-pack of beer for a rod and reel, a selection of lures, and some spare line. Once across the Atlantic, he entered a 60-mile feeder race from Porto Sherry to the rallys start off Huelva, during which he popped a new spinnaker emblazoned with the cross of the Knights of Christ, carried by Columbus caravels.

Perhaps symbolic of Columbus travails and his ability to overcome them, that same chute was lost en route to Madeira during a crash jibe in which Hunk-A-Schmitt was dismasted. Unfazed, like Columbus, Hank kept moving east and south, motoring the rest of the way to Madeira, where he ordered a new mast, and then on to the Canaries, where he had the spar stepped in time for the start of the leg to San Salvador.

When told that learning curves among the NARC crews were angled sharply upwards during last falls edition, Hank said, “I dont hold their hands.” No surprises here for this 44-year-old; nobody ever held his. So his Offshore Passage Opportunities Passage Guide, referring to the autumn gales and the capricious Gulf Stream, doesnt pull any punches: “The fall departure may scare the less experienced.” And the NARCs “Rules and Regulations” state in the very first sentence, “We work with the assumption that anyone planning to go offshore to the Caribbean in the fall understands how to get his or her boat ready and will be prepared before departure.”

And therein lay the rub for 59-year-old Miami periodontist Steve Chase. Chase paid the standard NARC rate of $2,365 for a berth on one of the Nautor Swans and concluded during the rally that the Swan 46 Pipe Dream, skippered by Captain Bryan Treadwell, was inadequately prepared for the late-fall passage to St. Martin. Chase had signed up with the NARC to add sea miles to his résumé. “The safety features I expected to see on the boat I was on were just not present,” he said upon his return to Florida. “There was no EPIRB, no SSB, no permanently installed GPS, no radar, no cabin-top handrails, and no jacklines. Had anything serious occurred, my satellite phone wouldve been the only thing to save us. When you pay that much for an offshore experience, you expect a certain professionalism applied to the process. But my main concern is that such oversights dont occur on future NARCs.”

Pipe Dream crewmate Clay Sanborn, whod sailed transatlantic with both Schmitt and Treadwell, doesnt agree with Chase. “Essentially, youre paying to do a boat delivery in November, and the reward is good heavy-weather, offshore experience,” he said. “Sure, some of this gear was missing, but in terms of being seaworthy, safe, and Coast Guard-approved, skippers like Bryan and Hank are there. But before you sign up, you better think long and hard about what youre doing. This is real-world stuff; its rough out there.”

Schmitt shares the burden here. “I should take some responsibility for not making sure this boat was in better shape,” he said. “However, the individual captains do, in fact, have an even greater responsibility for getting their boats ready for sea. And the crews have some personal accountability here, too. This is what OPO and the NARC are all about. Jacklines could have easily been run by any crewmember using spinnaker sheets or dock lines. Stuff happens and things break. We learn, and things get fixed.”

For the most part, complaints were few and far between. Aboard Hinano, no hands were held during that Force 10 storm, and no signs of anxiety were evident among her crew of seven. I’m of the shorten-sail-and-run-before-it persuasion, so I smiled when Hinano bore off to the east, the slamming stopped, and she was no longer sailing on her ear. Among my crewmates, I couldn’t detect even marginal concern as she climbed up the backs of massive storm-driven waves, seesawed over their breaking crests, put them on her quarter, and accelerated down into the troughs.

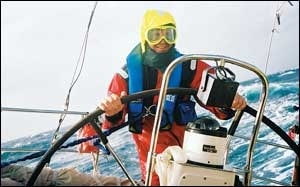

Instead, I saw the likes of 39-year-old expat Brit Andrew Chandler, of Snowbird, Utah, begoggled against the stinging spray, driving Hinano with a maniacal grin and screaming at the top of his lungs, apparently imploring Thor, the Viking god of storms, to permit him the honor of steering the boat all the way to Bermuda. “I’m not able to be happy unless I’m a little uncomfortable,” Andrew, a full-time adventurer and adrenaline junkie, said sheepishly. “As a fairly novice sailor, I didn’t know when to feel scared, and I wanted to find out. But I still don’t.” Ah, the bliss of inexperience.

In the wee hours one morning as I went on watch, I saw former corporate vice president and treasurer Julie Jacob, 35, from Grapevine, Texas, at the nav station, which looked more like a mechanical bull, inputting positions of the other NARC boats on the laptop so wed have that data on our hard drive. “I took this trip to find the freedom to follow my dream of cruising the world,” said Julie. “Our voyage reminded me how much I need adventure and passion–that I must follow my dream sooner, not later.”

Green water would later wash Julie out of Hinanos cockpit, wrapping her backward around a primary winch before she headed overboard under the lifelines, saved at the last moment by her tether. Sidelined by a hairline fracture in the joint between her pelvic bone and her sacrum, and in great pain the rest of the way to Bermuda, Julie remained cheerful and focused on the passage. “I found my own strength and stride with every wave and roll the sea threw at me,” she said.

I watched 36-year-old web-systems engineer Rebecca Taft, from Hull, Massachusetts–co-owner, with her husband, of the Valiant 40 Yellow Rose and veteran of a couple of offshore passages–prepare a brilliant spaghetti dinner for seven in the pitching galley, despite persistent seasickness. Rebecca wanted to test her endurance, to know how the rigors of an offshore passage would affect her over time. “Even when things were miserable during the storm, a part of me was laughing with glee,” she said. “With each passing day, I wanted to stay out longer, until I didnt want to reach land at all.”

For 1,500 miles, I followed on watch 52-year-old contractor Jim Byrnes, from Aspen, Colorado, and I was invariably greeted with an ear-to-ear grin and words of good cheer, no matter what the conditions. Jim wanted to log a classic passage like Newport to Bermuda and to gain offshore experience. “Being out on the ocean during a storm was a magical experience for me,” said Jim, who kept a personal log during the NARC and captured these moments: “waves the size of houses, dolphins leaping out from their faces and flying to the troughs below, opening the hatch at 0400 to a scene from The Perfect Storm.”

Career consultant and former United Nations staffer Lee Ann Avery, 44, from Granby, Connecticut, who joined Hinano on the NARCs first leg, sailing the second on a J/46 “to see what it was like,” shot rolls of film during the roughest weather, despite a traumatized digestive tract, and she provided comforting hugs to all crewmembers in need. “We all worked together to ensure not just our mutual safety but also comfort and enjoyment,” said Lee Ann, whod sailed before the mast on several OPO-generated passages. “For the first three days, I survived on peanut butter-and-jelly sandwiches made for me by my new friends.” A licensed captain, Lee Ann had excelled inshore but knew that an offshore passage–“when you must keep the boat running without the safety net of a marina when the weather acts up or gear fails”–would challenge her to learn more about voyaging-boat systems and heavy-weather management.

Clearly, Hinanos crew was a committed and well-adjusted bunch–for me, there have been no finer shipmates–but there was so much more to this disparate group that quickly gelled into a force infinitely greater than its parts. Not a harsh word was spoken during 10 days and 1,500 miles at sea, despite moments that were intense. “Egos were left on land,” said Lee Ann. “Everyone had skills that contributed to the cruise and appreciation of their fellow crewmembers. It was amazing how a group of seven people whod just met could, in just a few days, form a supportive team and make friendships that will last a lifetime.”

All that said, with many offshore miles under my belt and a wonderful woman named Naomi waiting at home for me, during my first long-distance cruising rally it occurred to me on more than one occasion that my biggest priority was getting ashore in one piece. As a disciple of Adlard Coles and his Heavy Weather Sailing, for more than three decades the bible of storm management, I knew, plain and simply, that you don’t willingly head offshore with a forecast such as we’d received.

On Hinano, landfall on Bermuda seemed unwelcomed and anticlimactic–most of the crew wanted to keep moving south–and with a crew not overly anxious to see land, the refracted image of Gibbs Hill Light was shimmering abeam as an afterthought by the time it was seen. As we passed the North East Breaker beacon, a tiny triangle of sail was approaching Town Cut, the entrance to St. George’s Harbour, five miles to the south of us, and we knew we’d finish second, by less than an hour, to Pipe Dream in this cruisers’ race disguised as a rally.

Once in St. Georges, rally director Hank Schmitt–who doubled as captain of the Swan 48 Caribe–soon set up shop at the dockside pay phone behind Triminghams, calling NARC Mission Control back in Huntington, making reservations, ordering parts, directing skippers and crews to the services theyd need, and schmoozing with old Bermudian friends and OPO members passing through on their way to the Caribbean. One of the latter, delivery skipper David Appleton, had ferried Palm Coaster, a Lagoon 41 catamaran, through the storm with a crew of three. In wind in the 50s and “huge” seas, hed issued a pan-pan signal–answered cheerily by a Bermuda Harbour Radio watch officer–when water began gushing through a seam in the transom steps, flooding the port engine compartment and threatening to sink the boat. “Things were going to hell in a hurry,” he said to Hank, a nervous smile crinkling his weatherbeaten face.

As the remaining NARC boats trickled in, the parties grew from intimate gatherings of a dozen or so revelers at Freddies Pub to close to 100 at a fish fry at the St. Georges Dinghy and Sports Club. Sea tales grew apace with the crowds and the number of Dark n Stormies and Carib beers consumed, and an eavesdropper might have thought it a miracle that so many sailors survived to spin their yarns. “I really liked the rally concept for this reason,” said Jim Byrnes. “It provided a great group of people to compare notes with on the passages: Soooooo–what broke on your boat? The stories and the camaraderie were just great.”

And the beat went on, along with the perversity of the weather. On November 11, with a forecast for stiff southerly winds, the fleet set sail for St. Martin, about 850 miles down the line. For three days, the wind averaged more than 20 knots true on the nose, then clocked into the southwest, allowing Hinano to make easting for more than half a day in anticipation of easterly trade winds.

Aloft, the skies were clear both night and day. The sunrises crafted cathedrals from gilded trade-wind clouds, the sunsets blazed a wild, fiery red, and the night skies were the stuff of Celtic legend: Silver-rimmed clouds, backlit by the moon, scudded across ink-black skies sparkling with stars and raked by meteor showers. Alow, when the wind dropped, Hinanos crew swam and showered on the transom steps, took sun sights, and scanned the horizon for the highlands of St. Martin, which materialized out of the haze four and a half days after leaving Bermuda.

With the Stones belting out “Satisfaction” from the cockpit speakers–choruses boisterously reinforced by the crew–Hinano charged into Anse Marcel bay to establish a beachhead in front of the Carbet Pool Bar at Le Meridien Le Domaine de Lonvilliers–a long name for the site of an unexpectedly short night. The rum burned on the way down, the reggae was intoxicating, and the line dance led to the deep end of the pool. Our clothes would be dry by morning.

Back on Hinano, after days of diligent and detailed log keeping, the last entry, by a bent but not broken Julie Jacob, read, “Latitude: Saint; Longitude: Martin.” What more was there to say?

Nim Marsh is a CW associate editor. For details about OPO and the NARC, visit their website (www.sailopo.com).