Summer was almost over. I’d been itching for an adventure, something to reconnect me with sailing and the world outside the confines of office walls, when a call came out of the blue from my longtime friend and sailing co-conspirator Carol Hasse. “Let’s sail to Sucia Island on Lorraine,” she proposed.

The timing was perfect.

Hasse, or Hasse-san as her friends call her, and I had made long Pacific Ocean passages together to exotic isles while teaching aboard the 65-foot sail training vessel Alaska Eagle. We’d taught countless Take the Helm seminars, even done separate stints as Cruising World Boat of the Year judges. However, we’d never sailed purely for pleasure together in our own Pacific Northwest backyard.

Hasse and I have a trust and comfort level forged over 30 years of friendship and some dicey situations aboard boats. And when I think to myself who is wise, who sees the best in others, whose life lessons I can learn from—it’s Hasse. No matter how long it has been, we pick up where we left off, and when we’re together, adventures effortlessly unfold.

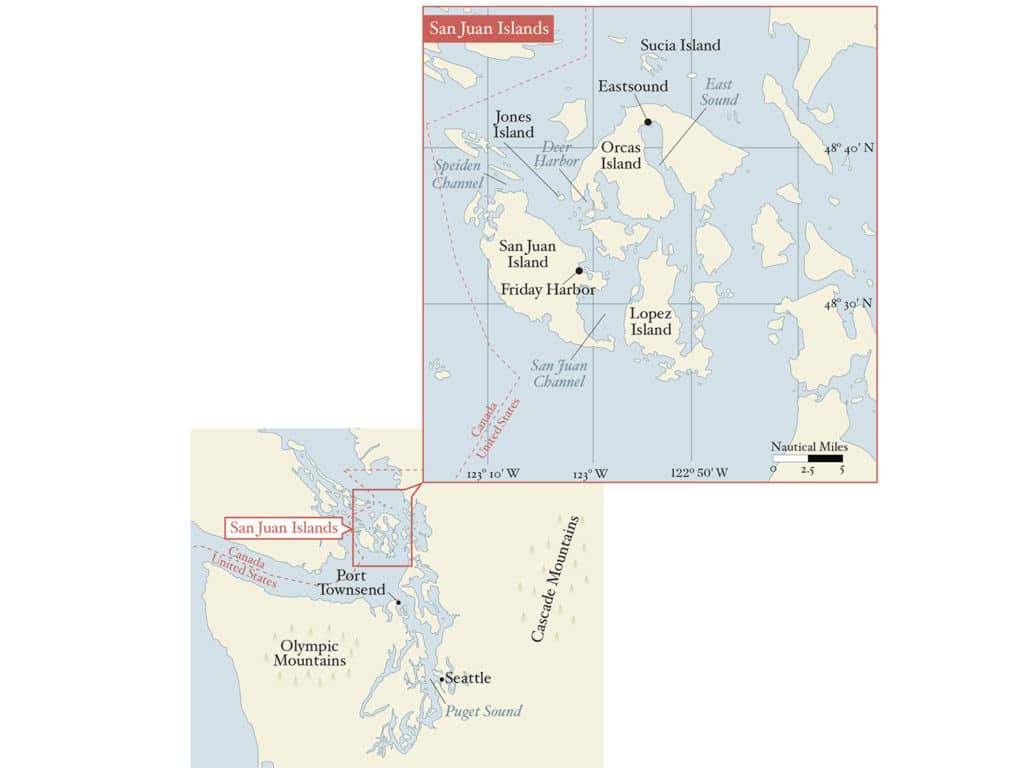

Although I live in the San Juan Islands of Washington state, a world-renowned cruising ground, in a case of the shoemaker’s children who often go barefoot, I no longer own a boat and spend most of my time in front of a computer, promoting the islands for others to visit.

Port Townsend, Hasse’s homeport, and my hometown of Friday Harbor on San Juan Island are only about 30 nautical miles apart by water. It’s double the distance by car and involves two ferry rides; that fact, and mutually busy lives, keep us from getting together often. But by using the water as our connection, we were about to sail in the wake of Coast Salish Natives who used the Salish Sea as their highway for millennia.

To get to San Juan Island, Hasse had sailed Lorraine with our mutual friend, Ace Sprague, from Port Townsend to Friday Harbor. As Ace left Lorraine and I stepped aboard, a neighboring boat owner wandered over to admire Lorraine, observed me and Hasse and asked, “Sisters, right?”

“No, but we get that question a lot,” I replied.

Hasse has always spoken with reverence about Lorraine, her classic 25-foot Nordic Folk Boat, named after her mother, so I was anxious to get acquainted under sail. Built in 1959, in Denmark, Lorraine and Hasse have been going steady since 1979.

In the decades I’ve known Hasse, Lorraine has been almost completely rebuilt by many of Port Townsend’s most skilled wooden-boat craftsmen. As we got underway for Jones Island, Hasse lovingly pointed out the portlight from the 80-year-old cutter Vito Dumas; the cedar privy bucket made by A.J. Correa; and how easily Lorraine’s sails hoist without the need for halyard winches. Despite Lorraine’s compact size, I found the cockpit roomy, easy to negotiate, and filled with lovely antique bronze fittings. As we headed north, it was like sailing back in time.

Jones Island Treats

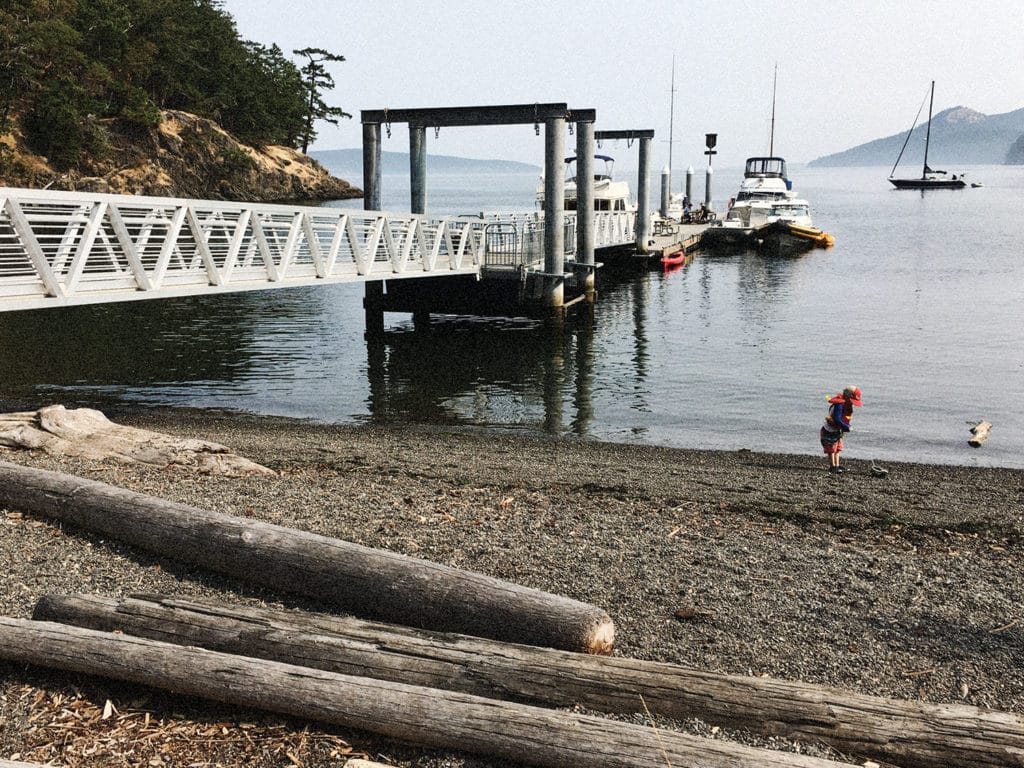

For a small boat, Jones Island is the perfect steppingstone to Sucia Island when coming from the more southerly San Juan Islands. During a 6-mile broad reach in light southerlies up San Juan Channel, Hasse and I eased back into our friendship. Shortly after arriving, we rendezvoused with Hasse’s godson, Spencer Snapp, and his family at anchor in North Cove at Jones Island Marine Park. It was August, so the half-dozen mooring buoys and space at the dock were taken by mid-afternoon. We tied up against a yellow pontoon on Spencer’s aptly named 30-foot Protector RIB. Our side-by-side boats looked like Laurel and Hardy.

Spencer, who grew up sailing on Lorraine, and I quickly bonded as members of the Hasse fan club, a society that numbers in the thousands thanks to her skill as an offshore sailmaker and her passion as a teacher. Her Port Townsend Sails loft, celebrating its 40th year, is renowned for both building beautifully handcrafted bluewater sails and for befriending its far-flung customers.

Our evening walk with the Snapps took us past grazing deer and moss-covered logs to the quieter, more-exposed southern side of the island. Once back aboard Lorraine, it was dark and peaceful, with only a dozen anchor lights twinkling. Hasse and my conversation turned to aging. She wondered how much longer she’ll be able to climb ladders to measure for sails, and I shared that I no longer feel super confident scrambling around a pitching deck in rough seas. But somehow age limitations are less onerous when shared with a close friend who still has a curious spirit and spring in her step.

And then the talk took a more playful turn as we recalled our shared Alaska Eagle adventures, like the time we were so focused on teaching sail trim that our students almost ran the boat into the barrier reef on Raiatea in the Society Islands.

As mates on Eagle’s first all-women ocean passage—from Honolulu to Friday Harbor—we recalled how 50 percent of the crew was green in our “Broad Way” show the first night out. To add levity, we called it the Women’s International Hurling contest. Capt. Karen Prioleau’s watch became “Prioleau’s Pukers,” Hasse’s became “Hasse’s Heavers” and my watch was “Barb’s Barf-o-Rama” (reminiscent of the pie-eating contest in the movie Stand by Me).

We recounted the Eagle halfway party, where costumes were created from whatever was aboard. How Capt. Karen created a hilarious Miss Piggy costume using a spray-can cap as a nose and plastic bags cut into strips to make false eyelashes. We remembered seeing flying fish under the Milky Way, rainbows after squalls, and the florescent streaks of dolphins at night, all during that same passage.

Hasse and I drifted to sleep on Lorraine’s settees, happy to be together on a new adventure without having to stand our long night watch or take care of seasick shipmates.

The next morning, we missed slack water, and motored out against the current instead. Believing there was enough wind to sail, we cut the engine. Mistake. We both know better; currents are strong in the islands, and summer winds are usually light and inconsistent.

Lorraine can easily sail in 4 knots of breeze, but could not overcome the increasing 1.5-knot ebb current. Instead, we were sucked west toward Spieden Channel, close to the rocky shoreline of San Juan Island, farther and farther from Sucia Island, our destination. The briny smell of bull kelp beds, signifying the water is growing shallower, wafted toward us. We could hear the distant grunts of Steller sea lions.

Hasse and her outboard, the “Wee Beastie,” do not share many Zen moments. It reluctantly started, sputtered and died. Yet the ever-vigilant Hasse was thinking ahead to every possible scenario: Should we ride the increasing 2-knot current up Spieden Channel to Stuart Island Marine Park? Return to Jones Island? Or try to tie up to a friend’s mooring buoy on Waldron Island? She weighed the merits of each.

Finally, the outboard kicked over. The tide had turned, and a 1-knot flood current in President Channel combined with the 4 hp. Beastie helped us make good progress toward Sucia. Summer light lingered late and worked in our favor. After drifting and motorsailing seven hours to cover 10 nautical miles, we entered Fox Cove on Sucia Island.

Sucia Island Surprises

Sucia is considered the crown jewel of the San Juan Islands’ 11 state marine parks. Shell middens from Coast Salish Native Americans are all that remain of their presence on the island. Rumrunners, smugglers and homesteaders followed. Today, the whole island is undeveloped.

One could spend a week here at a different bay, cove or dock every night, each with its own special allure: Snoring Bay with its seaweed-rimmed shore, or Shallow Bay’s sensuous sandstone caves. Washington’s first dinosaur bone, from a relative of Tyrannosaurus rex, was found in Sucia’s Fossil Bay among 70-million-year-old fossils from a shallow, near-tropical sea. Fossil Bay also contains Sucia’s only two docks and shoreside picnic shelter, both popular with cruisers.

It’s easy to understand why, of all the places Neil Young might have chosen to marry Daryl Hannah, he selected the stern of his boat, W.N. Ragland, in an ultraprivate ceremony anchored in Echo Bay with its view of snowcapped Mount Baker—just a few weeks before our visit.

Like many classic Pacific Northwest wooden boats, Hasse shared a history with Ragland, a 101-foot Baltic gaff-rigged schooner. Hasse’s first ocean passage, from Mexico to the Marquesas, was on Ragland. She subsequently met Young and made the vessel’s signature tanbark sails.

By 1830, we were making our way into Fox Cove. The sun was casting a golden glow on the anchorage. A blue heron waded silently in the shallows. Bizarre and baroque sandstone formations lined the shore, some delicately eroded like lace, while some formed into molarlike boulders, seemingly plucked from a giant’s jaw.

Amazed to find a mooring buoy available this late in the day, we soon discovered why. That night, the current flooding into the south entrance of the cove prevented us from swinging into the east wind. The buoy rapped urgently against Lorraine’s lapstrake hull, like an angry neighbor beating on our door. In my not-quite-wakeful state, I put up with the annoying noise rather than getting up and dealing with it. In the morning, rigging flat fenders on either side of the bow helped tame the beast.

We spent the day hiking Sucia’s network of trails past towering cedar trees and driftwood-strewn beaches, sharing stories of our parent’s lives and how different our own lives have unfolded from theirs. We felat safe sharing our secrets, knowing we wouldn’t be judged.

I was surprised later in the day when two-time circumnavigator Nancy Erley and our aforementioned friend and sailing instructor, Ace, brought Ace’s new-to-her Sea Dory 25 from Port Townsend to rendezvous with us at Shallow Bay. It was a bit of déjà vu as well. My first experience sailing was taking a cruising seminar from John Neal—well-known for his Mahina Expeditions—alongside Hasse and Nancy in Tahiti in 1984, before we’d all go on to careers teaching or writing about sailing.

We tied our boats together on one mooring buoy for the night. We talked about mutual sailing friends, past and present. The fruits of the Sea Dory’s onboard amenities (unlike Lorraine) included refrigeration, cellphone charging, and a head with a holding tank (we’d been using pit toilets ashore). All were greatly appreciated by the crew of Lorraine.

Deer Harbor Delights

After two nights on Sucia dealing with angry mooring buoys, we rode the ebb current to Deer Harbor on Orcas Island, tacking into light southerlies for 12 nautical miles. It was a sparkling Pacific Northwest sunny day, the smoke from recent British Columbia forest fires had finally cleared after several weeks of hazy skies.

We looked forward to hot showers, cold beer and freshly baked pizza as we snagged one of the last remaining side ties at Deer Harbor Marina. Instead, we found everything closed—island-wide. A truck had struck a power pole and knocked out electricity hours earlier. Perhaps in self-defense, marina management opened the restroom just for us.

Our sunset stroll through the hamlet of Deer Harbor crossed a bridge where, beneath us, a lone woman with long flowing hair was rowing a classic wherry. For all the world, she looked like the Lady of Shallot in John William Waterhouse’s painting by the same name.

I tentatively called out, “Kat?” Then her partner, Michael, who had been relaxing in the bottom of the boat, appeared. Michael and I have raced together on their painstakingly restored classic 6-meter, Challenge, commissioned by Cornelius Shields in 1934. What a coincidence.

Perhaps not surprisingly, then, I found out that Hasse had known Michael for decades. When Hasse and I are together, we always seem to run into someone one or both of us knows, whether it’s sailing in Tahiti or gunkholing in the Pacific Northwest. The owners of Deer Harbor Boatworks, Michael Durland and Kat Fennel hold the San Juan islands’ only wooden-boat rendezvous every September. It’s a low-key island-style affair in between the Victoria Classic Boat Festival and the Port Townsend Wooden Boat Festival.

A long, spontaneous evening of candlelight, wine and political reflection unfolded in their loft perched over the Deer Harbor estuary. Hasse and I walked back to Lorraine, a bit like drunken sailors, laughing arm in arm with a borrowed headlamp from Michael to light the way.

The next day, hot showers ashore felt more delicious for having waited an extra day. Michael and Kat drove us into the artsy village of Eastsound to the farmers’ market. The aroma of freshly brewed, locally roasted coffee and wood-fired pizza was irresistible, making up for the previous evening’s power outage.

Over the course of our four-day cruise, I found Hasse’s positive attitude comforting. When I decried the ravages of aging, Hasse said: “Think of every one of your wrinkles as some great life experience. And Barbara, we get to be elders now, respected for our wisdom.”

A day on land has its familiar routine—we have roles to play. But cruising nurtures a dissolving of self and boundaries. I lost track of what day it was and was reminded of how connected and spontaneous the cruising world is. Most important, Hasse and I had renewed a friendship that has seen us through failures and triumphs, squalls and star-filled nights. There was and is an irreplaceable honesty and reassurance that goes with all that shared history.

While Hasse’s and my cruising dreams might be less ambitious than in the past, they need be no less magical. And, like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, as we discovered in the San Juans, when we go looking for adventure, we often have no further to look than our own backyard.

Barbara Marrett has been a contributing editor to Cruising World since 1993. She is a Friday Harbor Port Commissioner and licensed captain. Mahina Tiare, Pacific Passages, her South Pacific adventure book written with John Neal, is available as an e-book from Amazon.com.

The San Juans: What to Know If You Go

Check out the website for Washington State Parks for specific information on each of the 11 state marine parks in the San Juan Islands.

All docks and mooring buoys are on a first-come, first-served basis. Many docks are removed in fall and replaced in spring. Mooring buoys remain available year-round. Moorage is paid from 1300 to 0800. Mooring buoys will accommodate boats up to 45 feet. Rafting is permitted. All local parks offer campsites, mooring buoys, and composting or pit toilets. Many stops also have potable water.

Cruising the Pacific Northwest without auxiliary power is very challenging. Summer winds are typically light, currents are strong (often greater than 2.5 knots), and unmarked rocks and reefs are found in unexpected places.

Carry a copy of Current Atlas Juan de Fuca Strait to Strait of Georgia published by the Canadian Hydrographic Service. You must also have the current year’s accompanying Waggoner Tables to predict current direction and strength, by hour, for every tide, each day. The Atlas doesn’t predict slack water; you must also carry tidal current tables to predict slack water.

Be aware of colliding currents that can cause tide rips, and check the weather to see where wind and current might oppose each other causing rough seas.

Be aware of large tidal ranges when anchoring. Set your scope for five times the water depth at high tide. Also remember, the islands are in the “rain shadow” of the Olympic Mountains, receiving half the rainfall of the Seattle area and twice as much sunshine. Carry large-scale charts to find unmarked rocks and reefs—there are many. Also bring several hundred feet of polypropylene line as a shore tie for deep or tight anchorages. Finally, get a copy of the Waggoner Cruising Guide for invaluable cruising tips, customs information, anchorages, piloting, marina and fuel-dock information.