In the wild elasticity of time since coronavirus shadows began gathering, it feels like ages since we canceled plans for the South Pacific – yet it’s been barely a week.

Since February we’ve been in prepare / wait-and-see mode. The worst-case scenario, in early days, was rerouting to Tahiti; later, waiting out a delayed departure. In terms of seasonal weather, we could comfortably leave from Mexico as late as middle or late May; lots of time to decide! In hindsight, this rationalization earmarked my first stage of grieving for the loss of those plans: denial of the reality that was trying to get our attention, lights flashing.

When I wrote about provisioning for a pandemic, my heart of hearts wanted to believe that the deep stores we were packing onto Totem would be carrying us across the water to French Polynesia and beyond. That the methodology dovetailed with an approach anyone can use to think through stocking up for pandemic isolation was a tidy convenience. But the beliefs that had for a week been flitting in the edges of consciousness coalesced into reluctant acceptance that day. The telling moment of the mental shift was when my shopping buddy, Karri, offered to share a six-pack (hey, it’s Costco) of two-pound bags of masa (corn flour for tortillas) …and I declined. We can’t get that in Fiji, but it’s on every tienda / super-mini shelf in Mexico. I didn’t need it.

Later that day – March 16 – we texted our intended crew, advising him that plans were on hold. Jamie and I slowed down our manic prep pace long enough to do some concerned thinking: wait-and-see no longer made sense, even with a two-month window to dawdle. We would not go to the South Pacific this year.

If you had told me even a month ago that we couldn’t sail to French Polynesia this year, I would have been crushed. Devastated! We love Mexico, but our feet are itchy: everyone aboard is very ready for passage-making to fresh horizons again. The possibility of not going was unfathomable until it was undeniable. But once we woke up to the reality, this was an easy decision to make.

- Coronavirus was spreading fast, and globally

- Sea time as quarantine is a fallacy for most crews; asymptomatic transmission could harbor a virus stowaway

- Remote countries and territories – perfectly exemplified by our intended island destinations – are particularly vulnerable; they do not have the medical facilities or transportation to cope

Those reasons are logical enough. Then, there’s action and reaction in our intended stops at that stage:

- Four days elapsed since French Polynesia had cut off cruise ships to repatriate their passengers

- Borders were closing (a few by the 16th; now, it’s nearly all Pacific island nations)

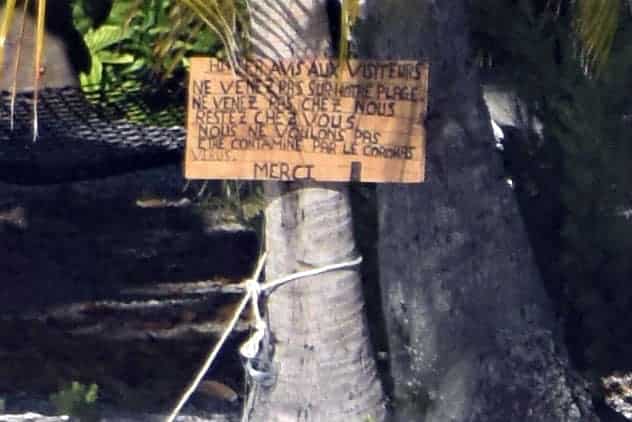

- Signs on beaches in French Polynesia asking visitors to stay on their boats and not come ashore

- Islanders’ comments in news articles and social media online expressing bitter feelings toward visitors

Is some of this surprising? When you consider that people of these islands were nearly wiped out by the diseases brought by European sailors to their shores in the 19th century, the growing xenophobia in the time of Coronavirus is easier to appreciate.

Right now, the people and government in French Polynesia might as well be beacons signaling “don’t go! you’re not wanted, you may hurt people!” On March 18, French Polynesia announced closure to non-residents and repatriation plans for existing visitors.

The next day, two options were outlined for new arrivals by sea. Simplified, these are: 1) you may provision and sail away (after 14 days quarantined at anchor – and to where? Most Pacific nations are now closed), or 2) you must sail to Tahiti to store your boat, and fly away. Staying was not an option; no more visas are granted. It’s been nearly a week, and since then, the country went into lockdown: everyone stays at home. For cruisers, even swimming around your boat is specifically prohibited.

Yet despite these messages, cruisers continue plans to go this season. Every day there are requests to join the Pacific Voyagers Facebook group from people who answer in the screening questions that they intend to depart. Even today, a boat departed from Panama bound for Marquesas, and others there contemplate the same – as if this was going to just blow over, near term. It is hard to see this as anything but choosing personal desire over greater good, at a time when the greater good really matters.

I had to wait a while to write this, for a few reasons. First, because I harbored deep stress and a lot of despair that boats continued to depart, or make active plans to depart – hearts set on sailing to the south seas. Second, to allow time to process some swirling emotions around these choices, and try and to understand and express them rationally. Third, because in the vortex that has been Coroninsanity, it feels each day there is a meaningful, further shift that’s necessary to roll into the full picture. The tipping point to put this down: that there aren’t more voices saying “don’t go!” – and a lot saying “but I think we still can!” Time to shift from posting factual updates to the news feed of Pacific Voyagers as they unfolded, and be frank.

The initial working titles (saved on my phone in awkward insomniac thumb typing) for this post are telling of my mindset:

- Don’t Go!

- Arrogant Cruisers

- What The Hell Are You Thinking?!

See, waiting was good! Now, as I process thoughts on how we’re all coping in the face of this unprecedented (in living memory) pandemic, these responses make more sense. An excellent HBR article illuminates how many of our reactions to the coronavirus pandemic are, in effect, signs of grieving. It outlines how we are grieving collectively, for what has changed and is lost. We are also grieving in an anticipatory way, for the uncertain future.

I’m trying to find compassion for those cruisers by filtering their decisions through expressions of grief. Denial: I won’t be part of the problem! Bargaining: I can help with my tourist dollars, they will be welcomed! Anger/defiance: I can go if I want! Grief, yes, but also I, I, I… self-centric expressions of personal desires, in person and email and social media, blind to begging otherwise for the greater good.

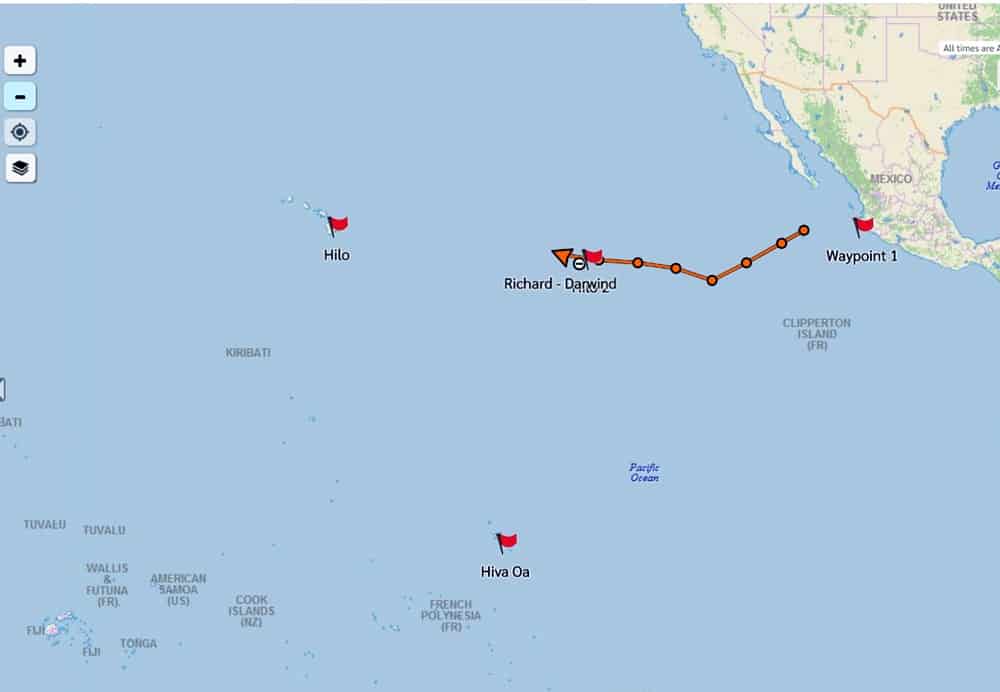

What about boats that left before those lights flashed brightly enough, or even did more than glow? Many wait under lockdown and quarantine, not quite cleared in, not really able to stay. Those with time to make routing changes largely have; it’s a diminishing set of options. In the South Pacific, just Fiji and American Samoa. In the North Pacific, Hawaii (with 14-day quarantine). The brave could route upwind to the Americas where only the USA, Mexico, Nicaragua remain open.

The impact of actions today on the reception of future arrivals is worth considering. The cumulative impact of the collective stress right now is hard to contemplate. There is a meaningful burden on those there now to be models of the best of cruiser culture. In the Marquesas, cruisers at anchor observe others failing to respect the articles of lockdown. All eyes are on them.

And then, even for those trying to do the right thing – departing before Coronavirus blew up, arriving in remote islands after the fact – their mere presence creates complication. Recent arrivals to Gambier islands shared their discomfort. “The locals do not want us here, and seem to feel we are bringing disease. Local authorities announced to all cruisers there were no provisions or fuel for cruisers. They report being overwhelmed by local needs. The supply ship left. All cruisers here need diesel, propane, and provisions. We are hoping another supply ship will come in the next month. But not sure they will have enough for us.”

In case that’s not clear enough, her partner offered: “For those who are contemplating it, I would humbly and respectfully propose that they seriously consider not leaving, and also consider the growing impact that all of us cruisers will have on the islands.”

What will Totem and crew do? There is a very real question of greater good when considering where to remain in Mexico, or if we remain in Mexico, and a lot to think about in working towards an ethical choice. Even though we are low risk, that “What If?” tickles the back of my mind. Should anyone on our boat need help – we could take resources away from someone else who needs it. It is incumbent on us – on all cruisers – to be model citizens in safe behaviors, if we choose to remain guests of a host country. Repatriation isn’t an option for us; we have to be very conscious instead.

For now, we’ve resumed life on our floating island – engine work completed, the umbilical cord of a marina cut. Our expectation is that we’ll meander north into the Sea of Cortez for hurricane season, but first, a period of self-isolation. We’ll try to make sure we’re OK, and stay tuned into what’s happening around us. It’s going to take a while, but we’re prepared – very prepared! Totem’s lockers are stuffed with provisions (dark chocolate, capers, gin…ok rice and beans), we generate our own power, some fuel is the tradeoff to make water, and there’s enough propane for several months with a solar oven to stretch even further. We’re hoping to keep largely to ourselves, enjoying socially-distant socializing once that feels appropriate again.

Is it stressful? Sure it is. We face an unknown future, like everyone else. It is the biggest shift that has ever happened in the lives of our kids, who don’t remember or weren’t born on 9/11. The economic hit coming could be very tough to our family, too (…our coaching service is OPEN again, by the way!).

If there is lightness to be found it’s in some of the memes going around. I’m still waiting for the one from a cruiser that cries out “ISOLATION – THIS IS WHAT WE’VE BEEN TRAINING FOR!”