When I woke, my seasickness had subsided to a general feeling of queasy unease, like snapping to in someone else’s house after a big night out. The constant slamming of the previous two days was gone, replaced with gyroscopic rigidity. The boat was on rails. The sea bubbled along the hull and a curious clicking sound tickled the side of the boat, like there was something loose in the bilge. But the noise came from outside: a pod of dolphins caressing us with their sonar. Other, subtler sounds filtered through. Distant music, melodious but indistinct. Was it whale song?

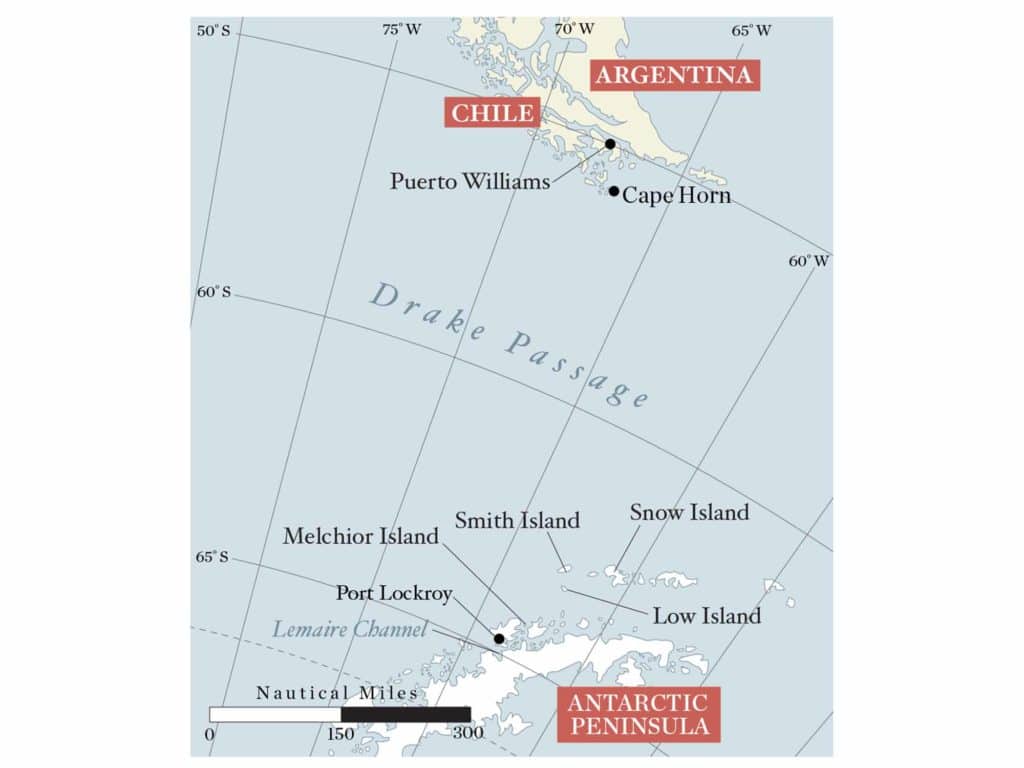

I was grateful to be free from the nausea, so grateful that it didn’t occur to me that the Southern Ocean should not be smooth, particularly Drake Passage, south of Cape Horn—the 500-nautical-mile stretch of big water separating South America from our destination of Antarctica. Not long after we’d departed from Puerto Williams, Chile, but before we had entered the Drake itself, I’d been struck with a cold sweat and irrepressible nausea. I filled a bucket with my breakfast and the boat with lamentation. Eventually Alec, the skipper, injected me with promethazine, probably more as a mercy to the rest of the crew than to me. Since then, I’d been cosseted in my bunk, gnawing at an energy bar during brief moments of consciousness.

I tried to get up and realized that all was not as it seemed. I had barely cocked my leg over the lee cloth when I was shoved back into my bunk by an unseen hand. I lay there peeved. I tried again, made it over the lee cloth, but stumbled against the bulkhead. I was a drunk trying to get dressed: a tangle of arms, legs and foul-weather gear. And yet the boat wasn’t moving. I didn’t understand.

I emerged from the cabin tentatively, clinging to handholds to make sure I didn’t fall over, and climbed the stairs to the pilothouse. We were riding a 4-meter swell; we were moving after all. My brain had just become attuned to the motion. The rest of the crew was on deck, watching an iceberg emerge from the haze off the port bow. At first little more than a pale silhouette, it grew into an island of towering white crags. Apparently, two days had passed; we were south of 60 degrees S, which explained the cold that suffused the boat.

Land remained elusive, beyond the bowed horizon but near enough for the arrival of seabirds. They skimmed the sea, breaking its skin with their breasts, daring it to pluck them from flight. A pair of whales emerged nearby, blasting frigid water from their blowholes. They dived back into the deep, water running from their slick skins like oil. Growlers, craggy bits of calved ice, hid themselves among the whitecaps. And between them, smaller shards, some shaped like birds that had frozen in flight and fallen into the water like forgotten ornaments.

Early in the morning of the third day, we sighted a shadow on the horizon: land. We had already slid unseen between Smith and Snow islands in an overcast twilight. Ironically, it was another isle, called Low, that first showed itself, only 4 miles to starboard. Seven hours later, we dropped anchor in the southwestern corner of Mikkelsen Harbor. We had arrived in Antarctica.

We’d completed the journey from Puerto Williams in just under three days aboard Pelagic Australis, Skip Novak’s 74-foot expedition sloop. We were 11 on board: three professional crew and the rest of us, whose experience ranged from very to none. Pelagic Australis is used for both tourist voyages and expeditions: mountaineering, skiing, diving and documentaries.

The pro crew comprised the skipper, Alec, his inimitable wife, Giselle, and Tom, a German mountaineer and sailor who looked remarkably like Capt. Haddock from The Adventures of Tintin comics. They were more than capable of sailing Pelagic Australis without any help, but the rest of us all stood watch and assisted with sailing duties.

RELATED: Unforgettable Antarctica

Before our Drake crossing, anything not fixed to the deck had been stowed below and strapped down. Now, before we could go ashore, the crew extricated the inflatable and its motor from the forward hold and assembled them. Tom ferried us to a flattish rock on D’Hainaut Island, where we carefully clambered onto the slick stone, and stood on the continent for the first time. The island measures less than 700 yards at its widest point, and is home to a cluster of seals and a colony of gentoo penguins. It was our first of many encounters with the captivating birds. We made our way through thigh-deep snow to a small rocky outcrop, next to the Argentine refuge that crowns the island, where the penguins had made a home.

Gentoos collect assorted rocks and pebbles to construct small stone circles for nests. While one parent sits on the eggs, the other fussily rearranges the stones, constantly shoring up their crumbling castle. But the number of loose stones on the island is finite, fewer than the penguins need. Consequently, they spend a lot of their time stealing stones from other nests in an infinite cycle of pilfering.

A sinister silhouette wheeled overhead. There were myriad nests for the skua to choose from, each holding a coveted meal of orange yolk cosseted in gelatinous albumen. The penguins responded to the imminent attack with flashing beaks and a rattling bray. But the skua was spoiled for choice, and it took only a careless moment—an instant of distraction—for it to seize an egg and fly off with it clamped in its beak. The skua landed nearby, cracked the shell and dipped into its rich reward. The bereft parents looked on glumly from their empty nest.

While most of us were engrossed by the penguins, Margie, an airline pilot, had other priorities. She stripped to her long johns and slid into the frigid water like a seal. And when he saw that he had been pipped, Eddie, a Scotsman, stripped to his goose pimples and waded out for a quick wallow. There were no other swimmers that day, but a challenge had been issued, and we would all, sooner or later, take a dip in the icy water.

We returned to the boat, raised anchor and, without a puff of wind to propel us, motored to Foyn Harbor, where we tied up to the rusting hulk of the Governøren, a Norwegian whaling ship that caught fire and sank there in 1915.

As an expedition vessel, Pelagic Australis carries most of the equipment needed for exploration on land and underwater. Among the “toys” aboard were two bright red inflatable kayaks, which were brought out and filled with air, adding color to the deck. My wife, Nicky, and I eased ourselves carefully into one and set off to explore some of the nearby inlets and coves. Having our bums below water level provided a new perspective. Soaring spires on our horizon hinted at ancient cities of ice; low dark shapes slipped between the cities like ships. It was unsettling, being away from the warmth and security of the boat, with handheld radios our only umbilical cord, as if we might slip into a void, never to be seen again.

That afternoon we donned snowshoes, climbed the hill overlooking the bay, and gained a different perspective. The vessel that had seemed so substantial when we crossed Drake Passage lay tied up below: a small and fragile thing in a landscape painted with a meager palette, a vista of infinite shades of blue and white. Snowy peaks stretched to the silent skyline, where they fused to the clouds. And, away from the babble of the penguin colonies, the jealous snow subsumed not only color, but sound too.

The following day we cast off from the Governøren and motored slowly into a bay of ice. Mist draped the mountains like a shroud, and a blanket of gray clouds hid the sun. Water lapped against the hull and trickled from ebbing icebergs.

Then, breath. A short, sharp explosion of air. A plume of water and frigid vapor pierced the scene as a humpback surfaced and blasted spent air from its lungs. Then another. The first noisily drew in a lungful of air, ducked its head and arched its back. Its tail slid from the sea, traced a trickling arc, then slipped back into the water. The whale disappeared, leaving only a ring of ripples as a reminder. Another surfaced, closer to us, and blew a cold cloud into the quiet air. And as we watched in silence, the whales dived and surfaced and blew and breathed and dived again; the bay echoed with their symphony.

When the whales submerged for the last time, we were left in frosty silence. We waited patiently for their return. When they didn’t, we departed reluctantly, like an enthused audience denied an encore. Pelagic swept us onward, down Gerlache Strait to Orne Harbor, where Spigot Peak hid itself in glowering clouds. The snow was firm enough to navigate without snowshoes, so we all went ashore and climbed to the col, where we found a small colony of chinstrap penguins safely ensconced. It seemed an extreme refuge, but the chinstraps were undeterred by the challenge and plied back and forth to the water some 500 feet below.

On the morning that we entered Lemaire Channel, the ice was sparse. A flurry of snow born by a fresh breeze brought a promise of sailing. We hoisted the main with two reefs and headed south along the eastern shore of Booth Island.

But after a few hours, the wind eased and the ice thickened, and Alec started the engine. We rounded the southern tip of Booth Island in polished water that reflected the mountains behind and inverted them in flawless symmetry. The kayaks were launched again, and four paddlers meandered to the anchorage in Salpêtrière Bay. We shadowed them in Pelagic, picking our way carefully between the icebergs.

The next morning there was too much ice for the inflatable, so Alec nosed Pelagic up to the rocks, and we disembarked over the bow. We quickly fragmented into isolated huddles of penguin watchers. The penguins, with their impossibly short legs and squat bodies, trundled up and down well-worn paths with their wings thrust out behind them like aged priests in tight cassocks, late for vespers.

RELATED: Sailing the Antarctic Island of South Georgia

Too soon ice began to crowd the bay, and we were recalled to the boat. We nudged through sheets of sea ice as flat as billiard tables, and bergs sculpted by wind and waves into intricate triumphal arches. Some were marbled with turquoise veins, while others harbored shallow grottoes with luminescent water and walls of iridescent blue.

We headed south, to Hovgaard Island, where we learned the value of the yacht’s lifting keel and the challenges of navigating in Antarctica. Alec was feeling his way into a bay when there was a loud metallic clunk, and the boat stopped. Despite his intimate knowledge of the area, we had hit an uncharted rock. We had been moving very slowly, so there was no damage, but it was a reminder of our isolation, our vulnerability and the potential consequences of getting something wrong in an unforgiving environment.

And then, too soon, it was time to plan the homeward journey. The relentless fronts and regular storms that lash the Drake meant that timing the return passage was crucial. Alec had analyzed the GRIBs and had chosen the upcoming Saturday as the best departure day. It would avoid the northerly gale that was forecast to reach Cape Horn in the early hours of the following Wednesday.

The news brought mixed feelings. Saturday was only three days away. The Drake was always going to be an ordeal, and one I would rather not subject myself to. But it’s part of the essence of being in Antarctica, and it must be endured. Our journey was always finite, but three days seemed like little more than a camera flash, and I didn’t want it to end.

Our imminent departure meant leaving tranquility and returning to a world that was dirty and noisy and crowded with the constant electronic chatter of mobile phones and televisions. We were filled with a new sense of urgency, a desire to make the most of every moment.

When we arrived at Port Lockroy, a sheet of ice still covered part of the bay and, with few opportunities to anchor, Alec drove Pelagic Australis into the ice, cleaving a red V into the shelf and creating a secure parking space for us.

After the solitude of the previous two weeks, Port Lockroy was a return to civilization, to a version of normality that I no longer desired. The station comprised a small cluster of black, painted buildings with red-framed windows perched on a small knoll. After lunch on board, we filed over the bow, down the boarding ladder onto the ice. At the world’s most southerly post office, we wrote postcards and succumbed to some souvenir shopping.

The following morning, we motored up the Neumayer Channel toward the Melchior Islands, home to another Argentine base, and a convenient departure point for the return voyage to Chile. On the way, we received a distress message about a trimaran that had capsized near Cape Horn in winds of over 70 knots. We were too far away to provide any assistance, but it was another reminder that the inescapable Drake Passage crossing was imminent.

Alec snugged Pelagic into a small inlet on Omega Island for the night. The next day was to be our last on the continent. Nicky reminded me that it was the final opportunity for an Antarctic swim, and persuaded Michiel and Aidan to join us. The water was black as night and littered with growlers. I held my nose and clamped my mouth shut, and Nicky and I jumped off the stern together. The water snatched the warmth from my body, and I fought the urge to gasp. Bubbles foamed around me, and I sank into the darkness. I kicked for the surface and emerged like a missile, gulping for air. The four of us scrambled back onto the boat and, still in our underwear, we posed for photographs, glowing pink in the relative warmth. And before hypothermia set in, we dashed downstairs for a welcome hot shower.

The next morning, Pelagic Australis raised anchor to sail back across Drake Passage for Cape Horn and Puerto Williams. I expected the worst and, with a sense of foreboding, slunk below to my bunk.

Brady Ridgway is the author of two novels and a professional pilot who, with his wife, Nicky, own an Ovni 435 that is currently on the hard in Greece after an eventful cruise through Europe and the Med after purchasing the boat in France. While current sailing plans are on hold, he is flying a Beech 1900 in the DR Congo on a peacekeeping mission for the United Nations.

High-Seas Charter Adventures

For the accompanying story, the author signed on with Skip Novak’s Pelagic Expeditions, which offers berths on a pair of custom, high-latitude yachts on voyages to the Arctic and Antarctic, Cape Horn, Spitsbergen, Greenland, South Georgia and the Falkland Islands. For more info on their destinations and itineraries, visit their website.