Aboard Quetzal, anchored off Christmas Cove, USVIs, April 5 2020.

Tempers were short as a newly arrived sloop anchored too close to his neighbor. Sailboats at anchor social distance naturally, but if they don’t, like in this case, a discussion ensues, sometimes a heated discussion, until somebody moves a lot more than 6 feet away. Cooler heads prevailed and the new boat re-anchored and blew socially responsible kisses to his neighbor, all was well. Sailors, cruising sailors in particular, are friendly, helpful almost to a fault, and quite social. Prickly Bay, one of several inlets along the serrated south shore of Grenada, is a cruiser’s retreat with room for a lot of boats. There are often more than 100 at anchor and on moorings, with flags dancing astern from all over the world. As anchorages go, Prickly Bay is not beautiful, at least by Caribbean standards, and it can be roiled by a stealthy swell. But it lies a smidge south of 12 degrees, a magical line in the water as far as insurance companies are concerned. It’s deemed safe during hurricane season. But last week, when I wrote this, (which seems like a lifetime ago) few if any boats had left and others were desperately trying to clear into Grenada months before the usual storm season rush. Of course, that’s the new reality of the cornonavirus pandemic. There are no guidebooks or GRIB files to help navigate this storm-tossed world.

Instagram posts aside, about how a sailboat is the only place to be during these challenging times, Caribbean sailors were beginning to feel like refugees as one island country after another closed its borders and told them to go away. My wife, Tadji, and I, aboard Quetzal, had just finished our latest onsite Caribbean Cruising Workshop as the COVID-19 crisis began to impact Grenada and the cruising fleet. Many of our friends were resigned to spending the next 6 to 7 months in Prickly Bay, to ride out the virus and hurricane season, which actuaries, not meteorologists, insist begins with the turn of June. Adam and Khiara, our young friends from Australia, were getting creative adding content to their YouTube Channel, “Sailing Millennial Falcon.” Our former shipmate Ric, aboard Endorfin II, has been cruising the Caribbean for years with his wife, Diane. Now she’s in Canada and he’s in Prickly Bay, resigned to a long separation. New friends from Brazil, Zac, Lorena, and their young son, Ian, aboard Ventura, were ready to make Grenada home base for as long as required. So it went, cruisers, nomads at heart, were forced to hunker down and stay put like everybody else in the world.

We chose to sail north to the U.S. Virgin Islands. Tadji wanted to be in U.S. waters and have accessibility to our children, friends and families, and no amount of cajoling was going to change her mind. Mainland flights were still coming and going into St. Thomas, that’s all she needed to know. Rumors, facts, and wild exaggerations vied for attention among increasingly alarmed cruisers trying to plot their next moves. Supposedly, the U.S. Virgin Islands were still letting boats clear in and anchor with impunity. Also, I was irrationally clinging to a sliver of hope that our training passage from St. Thomas to Annapolis, Maryland, scheduled for late April and crewed by good friends, might still take place. (It’s been postponed.) With all that in mind, I dinghied ashore to pick up our propane tanks, squeeze every last drop of diesel into our four jerry cans, and make one last run to the mini mart to top provisions. Coffee and wine carried the day, but in my defense, the store didn’t have much of a selection and we didn’t know if we’d be quarantined upon arrival in St Thomas. 14 days without wine would be difficult enough, 14 days without coffee, that’s survival.

With the dinghy lashed on the foredeck I hauled the anchor and Tadji steered for Point Saline. Around the barren southwest corner of Grenada, we set the main, staysail and genoa and made our way offshore on a generous reach. Quetzal stretched her wings in appreciation. And that was just the start; it turned out to be one of those sails.

Waves are always the wind’s messenger. A churned sea state let us know that the northeast trades were wrapping around Grenada’s lush northern headlands and would soon come our way. We fell off, keeping the apparent wind just aft of beam, and zipped along at 8 knots. I decided not to be a slave to a waypoint, not to turn the promise of one of the best sails in the hemisphere, not to mention the possibility of it being one our last sails for a while, into a desperate charge toward safe harbor. The route north from the bottom of the eastern Caribbean is invariably good going. We had 420 miles to sail, we’d get there in 2 ½ to 3 days. There would be headers and lifters as the trade winds filtered around and between islands, and there would be squalls and lulls in local pressure gradients, but mostly there be would hours of magical reaching. Armed with freshly downloaded GRIB files, it was obvious to even a casual observer that the winds would be favorable all the way. There was simply no reason not to unshackle our beautiful boat and let her go with the flow. We’d been staring into our phones for days, anxious for every news update, and didn’t want to spend the next three days staring at a line on the plotter, counting down miles and minutes, putting a self-imposed timeline on our splendid interlude.

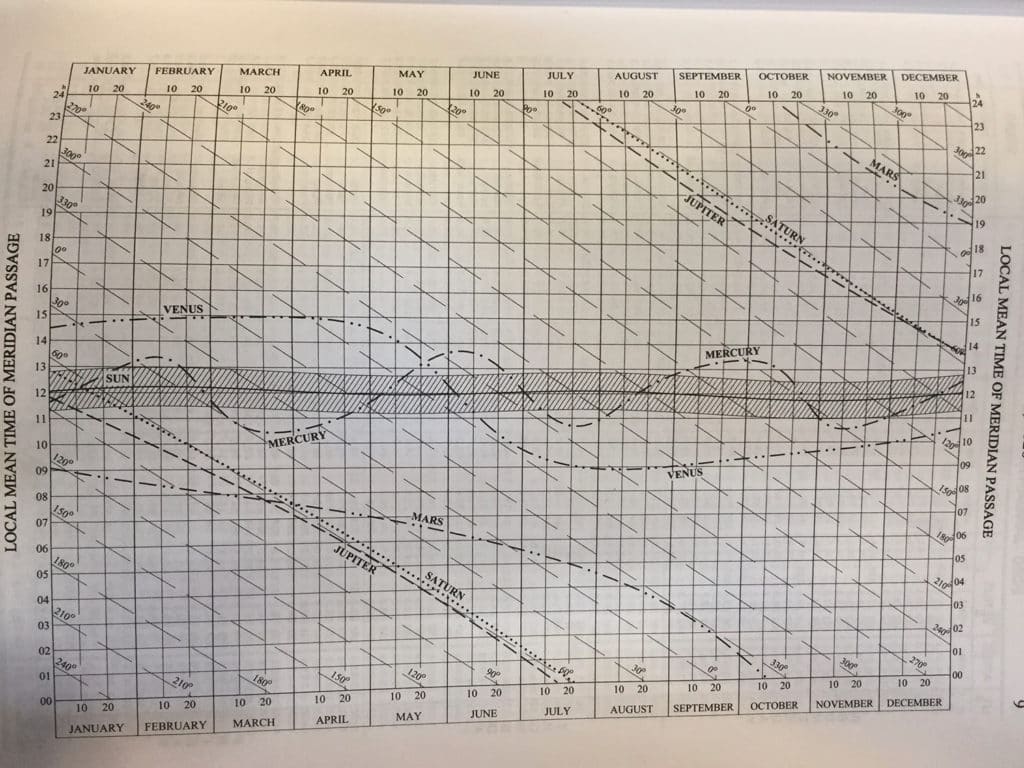

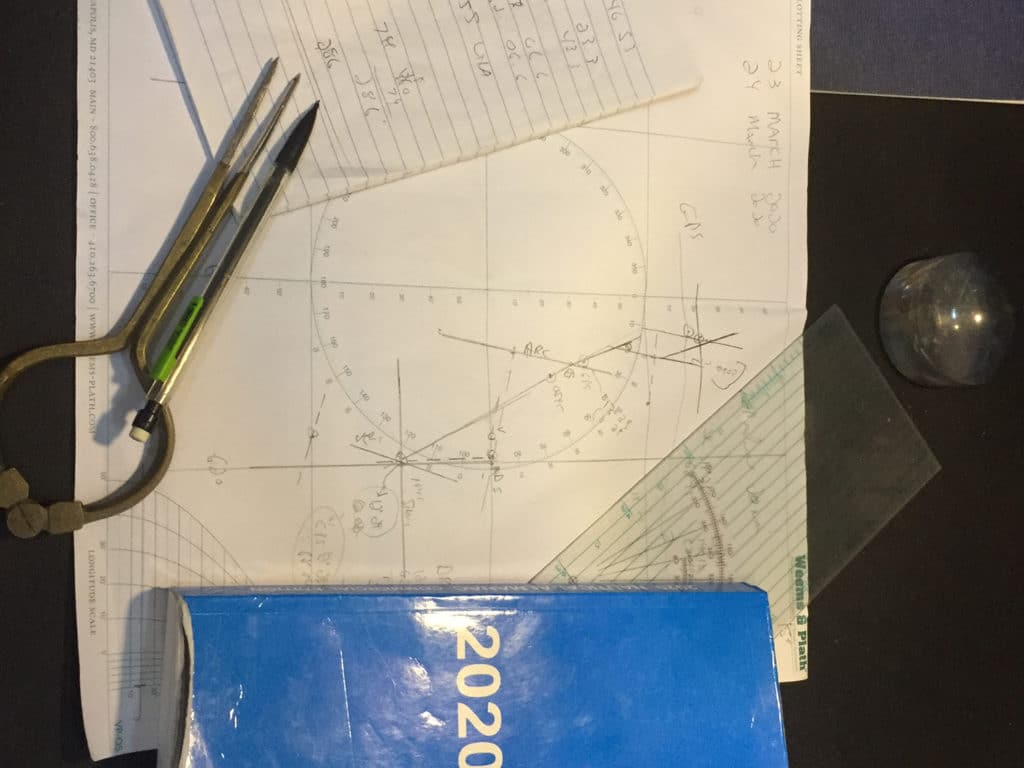

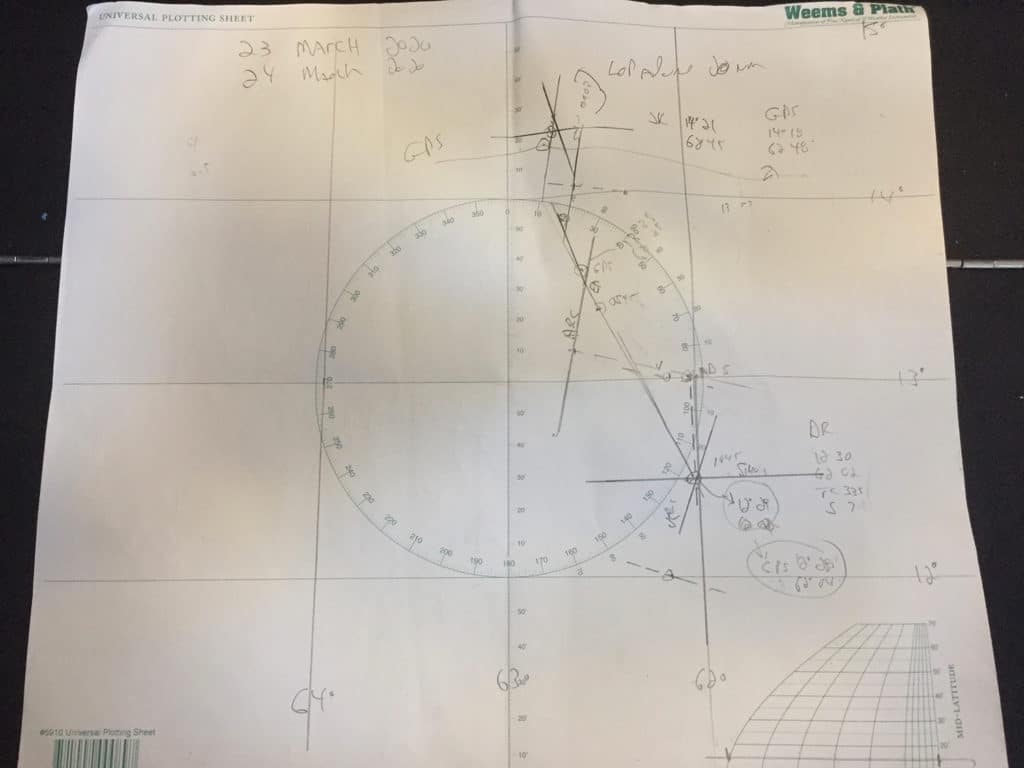

Twilight was cloudless, and even Tadji had to admit that a vivid green flash kissed the sun goodnight. She’s is a green flash denier, or was, and teases me that I need cataract surgery every time I claim to have seen the flash. Now? She’s still a skeptic, but there’s chink in her armor. I was determined to look at stars, not screens, and make time for celestial navigation. I teach celestial on every training passage; it’s one of my great passions. It was nice to putter around with the almanac and sight reduction tables, pre-calculating what stars and planets to shoot and not having to explain each step along the way. Twilight was elegant, even by tropical standards where darkness comes hard and fast. Peering over the port quarter with sextant and watch in hand, I took a series of sights on Venus and Sirius. I chose to take multiple sights on these two bodies because the lines of position from each would cross at 80 degrees, providing a nice fix. And they were brilliant. Venus, the glamourous goddess of twilight, was throwing glitter into the waves below. Sirius, the Dog Star, was preening, chasing Orion the Hunter. Then darkness, the total darkness that can only found on a moonless night at sea, enveloped Quetzal.

Tadji and I have a flexible watch system. She’s not a fan of getting up every three or four hours and prefers to take the first watch after dinner and stay up as late as she can. She usually makes it to at least midnight, often to 0100, sometimes even later, before waking me. After making a pot of coffee, I’m on duty until first light. While we both like the system, I was too entranced by the canopy of stars to head below, and I also wanted to reduce and plot my sights. She climbed into the starboard aft cabin, our underway sleeping bunk that has an easy motion and a hatch that opens into the cockpit. I dimmed the lights on the instruments completely. The darkness was inviting, I didn’t want to leave it. It felt safe and reassuring to be moving further offshore with every minute, with every wave. The Big Dipper was pointing the way toward the north star. We didn’t need the ship’s compass; we were headed two fists left of Polaris. Orion was getting ready to call it a night off to port, and Mintaka, the leading star in his belt, sets due west. We had our bearings, confirmed by the compass in the sea, the reliable easterly swell rolling us gently to port.

I eventually flipped on my head lamp and worked out the sights. Full disclosure: My time travel back to pre-satellite times was a tad dubious because I asked Tadji to jot down the GPS coordinates when I took my sights – just for comparison’s sake. The resulting lines of position produced a fix with coordinates, 12° 29’ N and 62° 02’ W. I just couldn’t help but check Tadji’s numbers in the log to compare, or as I later told her, to confirm that GPS had not been done in by the COVID-19 virus and was still working. She was not amused. We were less than 2 miles apart.

I roused her just after 2300 and climbed into the warm bunk. I asked to be woken at 0300. I wanted to see a rare trifecta of planets in the predawn sky. Back in the cockpit, with a cup of hot coffee in hand, we looked to the southeast. Jupiter, Saturn and Mars were bunched right next to each other like the piercings sandwiched into Tadji’s left ear. They reminded me of three basketball players confused by a zone defense, standing right next to each other instead of spreading out around the court. A single star, nearby Antares in my favorite constellation Scorpio, could handily cover all three superstar planets. Ok, enough basketball in the sky, but of all canceled events so far, I think I missed March Madness the most. Michigan State was peaking at just the right time!

I took the helm. The Hydrovane had been steering and doing a nice job of things but I wanted to chat with Quetzal and see what secrets she had to share. Blasting along on a beam reach, there was a bit of weather helm. I thought we might be happier with a reef in the main and a tuck in the headsail. Immediately I tried to banish the thoughts from my mind, telling myself that I didn’t really think them. My policy is simple: Once you think about reefing, you reef. I reefed. And Quetzal was happier, if a tad slower, but the ride was still fast, balanced and easy. I find myself steering by different inputs these days. While I use the slant of the waves for basic heading guidance, I also find that I can anticipate waves through my heels. Don’t laugh. Standing at the helm, my windward heel feels pressure just before the sea makes contact with the hull and I can start to steer down before riding the crest back up. After an hour of listening to my right heel, I locked the wheel and let Hydrovane take over.

Clouds spawned low on the eastern horizon began to spread across the sky, obscuring some of the stars I had hoped to take sights on at twilight. Arcturus was still visible, and with a later Sun LOP, would provide a decent and interesting running fix. The Southern Cross had also nosed above the horizon, with a rakish lean to starboard and I couldn’t help but start to sing. “When you see the Southern Cross for the first time…” But the stars had competition. Brilliant bursts of sparkly bioluminescence accompanied each wave rushing under the hull. It felt like Quetzal was riding a magic carpet of light. It was a wonder.

A red-streaked dawn lived up to the old saying, and we had a squally, gloomy second day. We didn’t care, the shade and cool temperatures were welcome, and Quetzal kept her pace. The cutter rig is made for across-the-wind sailing in capricious conditions. The apparent wind hovered between 20 and 25 knots, but gusts were often higher. We took the second reef in the main and played the gusts by furling the headsail in and out as needed, keeping the wind just aft of the beam, our happy spot. Robust furling gear, led to a winch that allows reefing with minimal luffing, and definitely without heading up, is essential to efficient ocean sailing. By late afternoon the clouds parted, the wind eased to 15 knots and we charged into the darkness under full sail.

Old friends, Venus and Sirius, provided another fix just after sunset, confirming that the GPS was still reasonably accurate. We resorted to our normal watch routine and the night flew by. The ocean south of the Virgin Islands was eerily empty, usually there is a flotilla of cruise ships lit up like small cities. We passed just east of St. Croix and at first light were 20 miles south of St. Thomas.

Just like that the stresses returned. Would we be able to clear in? Would we be quarantined? What was going on in United States, in the rest of world? Soon we’d have phone service and news, assuredly bad news, probably horrific news. We knew the kids were OK because they would have checked in via the sat phone, but otherwise the uncertainties were palpable. The wind eased and our speed dropped to 5 knots. Quetzal had unfinished business and was not ready for landfall. The wonders of a short, magical passage were already fading, forgotten as we steeled ourselves to re-enter a world gripped by fear and confusion.

I forced myself to steer away from those dark thoughts, at least for a few more hours. As Quetzal glided over a calming sea, taking her time, I recognized the familiar profiles of St. Thomas and St. John take shape. Over the years, as more miles wash under my keel, I have become philosophical. Or maybe I am just less restrained, and no doubt, more of a bore, as I dole out advice and so-called wisdom to those poor souls trapped aboard Quetzal. My contention, however, is simple: Time is the only thing that matters, it’s the currency of our life. How we spend it defines us. I believe that time spent sailing, especially deep ocean sailing, is time well spent. Even if it’s just a wondrous 2.5 days. As we eased toward familiar islands, I knew, like only an old sailor can know, that the current madness will pass. I knew that we’d do our part as humans, to help, to cure, and, to love each other. I also knew that I would continue to make voyages while I can, to leave myself open to the honesty and enlightenment that only the sea can deliver. It’s a wonder out there.

John Kretschmer’s latest book, Sailing to the Edge of Time, has just been released in paperback and as an audio book. John and his wife, Tadji, conduct offshore sail training passage aboard their well-traveled 47-foot cutter, Quetzal. In 2021 they will launch “The Big One,” a circumnavigation that will take them to latitudes big and small and longitudes far and wide. They will incorporate select training passages along the way and also report for Cruising World from far-flung quay sides.