You turn the wheel and your boat turns. It’s simple and fun on calm days, and exhilarating when the breeze builds. But have you ever turned the wheel and found that it just keeps spinning? Your heart jumps into your throat, and that sense of enjoyment, well, it evaporates. Your sailboat is out of control. Based on the conditions, this could mean an accidental jibe, roundup or collision with another vessel or obstruction. Your crew, your boat and nearby vessels are all at risk.

When analyzing a vessel for seaworthiness, the hull, hardware and associated systems can be broken down into tiers: essential, supporting and luxury. Essential items are vital for immediate continuance of a journey and the safety of those on board.

While the equipment in each tier may vary by captain, it is tough to argue that directional control is not critical. It is on the short list, right beside floating and some means of propulsion. After all, those are the three basic characteristics that define a boat.

I have spoken with boat owners who have consciously opted to ignore steering maintenance, suggesting that they could always fall back on an emergency tiller. That theory tends to deteriorate as soon as the skipper tries to remove the deck plate. If the steering system hasn’t been maintained, the threads on the deck plate will also have been neglected. Chances are good that the cover will be fused solid, thanks to the lovely effects of the sun and salt. Even if the emergency tiller is installed, using it is typically comparable to wrestling a baby grizzly bear for hours on end.

One alternative solution that isn’t always considered right away is a below-deck independent autopilot. In a crisis, it’s a solution, but only if the remainder of the steering system isn’t jammed up. If it is, the autopilot will fail quickly (hopefully, just the fuse will blow). And remember, with the autopilot working, there is now a consistent and considerable number of amps being drawn, meaning your vessel is one step closer to a complete steering failure. In the end, ignoring the maintenance of a primary system means there is no true redundancy. And redundancy and self-sufficiency are key aspects of proper seamanship. Answer this: Do you really want to be that case study that is examined at every Safety at Sea seminar?

Steering Options

Most sailboats have either mechanical or hydraulic steering. Of the two, mechanical mechanisms are preferred by many sailors because they deliver feedback to the helmsman, who instantly knows whether the sails need adjustments in order to sail a steadier course. Options include tiller, worm gear, rack-and-pinion, transmission (a series for torque tubes joined by bevel boxes, with an ultimate output to the rudderpost achieved by a drag link and tiller arm) and chain-and-wire. There are some exotic exceptions to this list, but they are rarely found on cruising sailboats.

If your boat has a hydraulic system, inspect it regularly. Fluids should be checked and topped off or replaced, ram shafts should be cleaned and greased, and any additional manufacturer recommendations should be followed. Spare parts and hydraulic fluid can be carried, but repairs at sea are challenging.

Turning attention to mechanical helms, it’s important to note that worm-gear, rack-and-pinion and transmission systems all follow the same rules for maintenance: inspect regularly and keep components greased. Rack-and-pinion, worm-gear and transmission systems may allow for adjustment as the gears wear, but otherwise, these systems need to be rebuilt or replaced once excessive play develops. Repairs at sea, for anything but the simplest of components, are near impossible, but that is often negated by their robustness. This is particularly the case for worm gears and traditional rack-and-pinion systems.

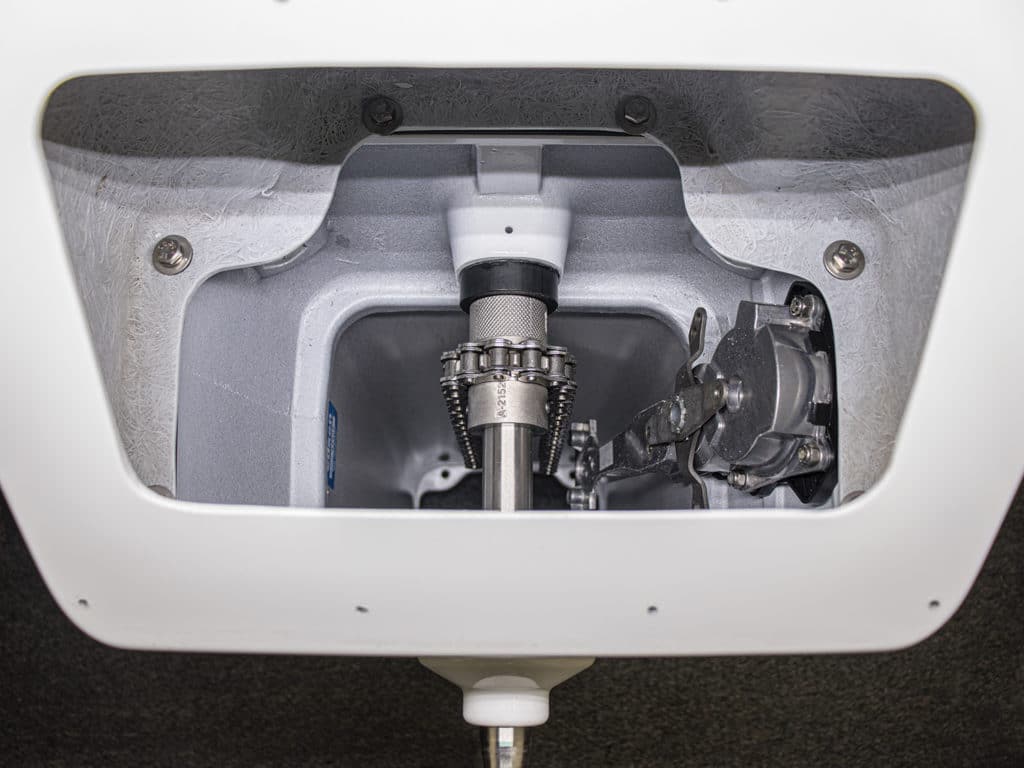

Chain-and-wire is by far the most common type of mechanical steering. It is beautifully simple in operation and allows for repairs at sea. Accessing every component is where the challenge is faced; it all depends on how well the boat was designed. In a typical system, a steering wheel is attached to a shaft that also contains a sprocket. A length of chain runs over that sprocket, with each chain end connected to flexible wire. The wires follow a series of sheaves and are secured to opposing sides of a quadrant or radial drive wheel, which in turn is attached to the rudderpost and underwater foil.

Chain-and-Wire Care

Inspection should occur at least on a yearly basis and before any ocean passage. Turn the wheel hard over in one direction, and then hard over in the other. Listen and feel for anything that resembles chafing, a high level of friction, excess play or inconsistencies in motion. When the wheel turns, the rudder should turn—any lag means that the cables are undertensioned. This is best done with assistance so that above- and below-deck components can be visually inspected while the system is in motion.

Before starting, all appropriate headliners and access panels should be removed to provide full access to the system, and every component should be examined. Secure rudder stops should be in place, such that the rudder is limited in travel and the chain cannot overrun the sprocket. Keep an eye out for wire misalignment and chafe, especially on new or recently refit vessels.

Isolate parts of the system to narrow down issues. For example, disconnecting the wire from the quadrant is a simple way to isolate the wheel shaft, rudder bearings and sheaves.

A chain-and-wire system requires regular lubrication. This protects components from excessive wear and corrosion. Chain and wire are best lubricated with a specialty product such as ChainCare+, which is specifically designed to penetrate chain links and remain in place to protect from crevice corrosion (full disclosure: it’s a product my company carries). A light engine oil can be used as an alternative, but more-frequent applications will be required. Grease is not appropriate here because it does not penetrate deeply enough.

Sheaves with Oilite bearings should be lubricated with light oil (try 30W engine oil). Sheaves that contain needle bearings, and any other needle bearings in the system, like those on the wheel shaft, should be lubricated with a Teflon grease such as Super Lube. Any length of wire that passes through conduit should also be lubricated with Teflon grease.

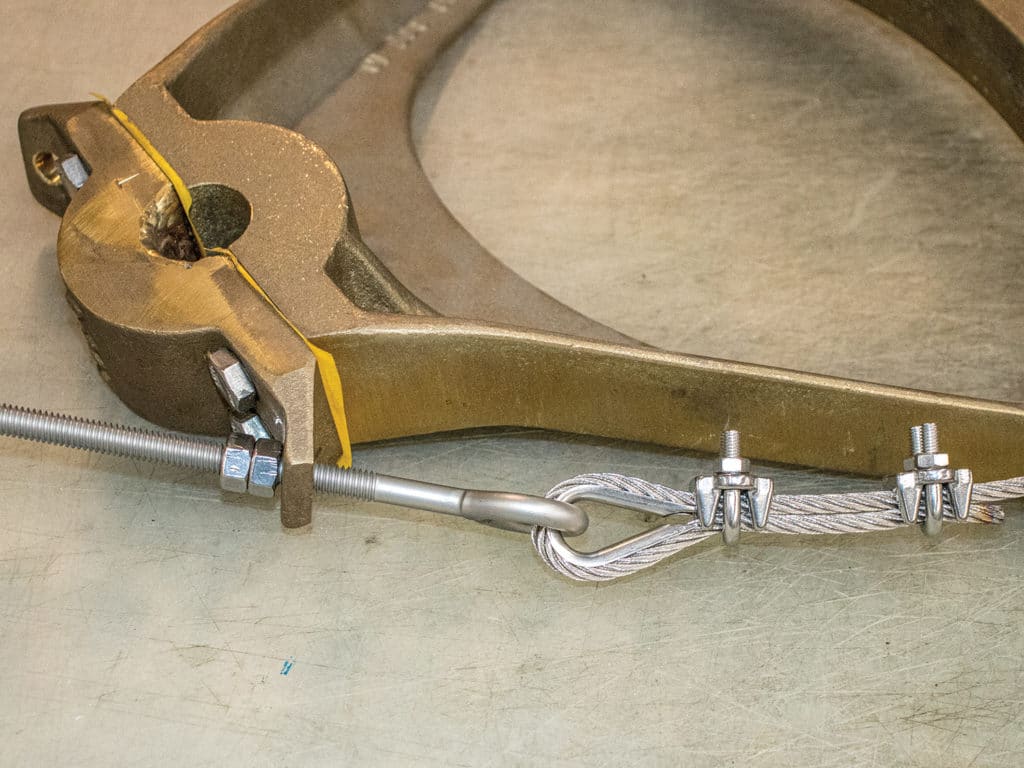

A well-maintained system will last longer. However, certain components will still wear out. The chain-and-wire assembly is the most important item to be replaced according to schedule: every seven to 10 years in a saltwater environment. This period represents a window safe from catastrophic crevice corrosion or fatigue. If extensive miles are placed on a vessel, that will shorten this recommended time frame. A visual inspection of steering wire may reveal broken wire strands, but at that point it is fortunate that the wire did not already fail. Furthermore, the hidden links of a roller chain cannot be inspected for crevice corrosion by eye without destructive disassembly. Recycling the old chain-and-wire and replacing it with a new kit is the safest and most cost-effective route.

Other components, such as bearings and snap rings, will also require eventual replacement. Larger parts, such as idlers (the sheave assembly directly below the pedestal) may succumb to corrosion due to water intrusion and require replacement. Pedestals will also eventually wear out but can be expected to last decades if proper care is taken.

The most common steering failure is due to lax wire tension—it is also the easiest failure to prevent. When steering, only one cable is loaded by the rudder. The other cable, or the lazy cable, can fall out of the groove of a sheave or quadrant if the pre-tension on the cables is incorrect. To check for proper tension, turn the wheel hard over and then apply another 40 pounds of force on the wheel rim (you are simulating a roundup situation). Below deck, one cable will be extremely taut, and the other will be loose. Carefully, have an assistant ensure that the lazy cable cannot be pulled out of any sheaves or the quadrant. If more tension is required to achieve this, tighten up both cables evenly, using the take-up eyes on the quadrant or radial wheel. Note that too much pre-tension will result in stiff steering and premature wear of bearing surfaces.

The rudder, rudderstock and rudder bearings should also be inspected. While on the hard, a visual inspection, combined with feeling the rudder for excessive play or binding, will go a long way in detecting issues.

Further steps can be taken to evaluate any encapsulated structure and the integrity of the rudderstock where it passes through the hull, but such work might be well beyond the scope of an annual checkup. Some rudder bearings require lubrication, but most are self-lubricating and just benefit from being flushed out with fresh water.

With regular inspection, lubrication and replacing key components, any vessel can have high confidence in maintaining directional control. But to play things safe, test all backup systems and make sure they are ready to deploy.

Adam Cove is CEO of Edson, a naval architect and zealous sailor. For more on steering systems and an inspection checklist see edson marine.com/content/EB-372-14_Steering_Inspection.pdf.

In a pinch

Faced with a loss of primary and backup steering systems, sailors sometimes turn to emergency external rudders and drogue steering, but these will obviously not perform as well as a primary system. Testing in fair conditions is different than setting up and implementing a jury-rigged rudder in a gale. Having these options is nothing short of brilliant, but they are a last resort and should not be a convenient excuse for ignoring steering-system maintenance.

Inspection tool list

- Headlamp

- Gloves

- Screwdrivers

- Fixed wrenches

- Allen wrenches

- Needle-nose pliers

- Snap-ring pliers

- Rubber mallet

- Lubricant such as ChainCare+ or 30W oil

- Teflon grease

- Rags

- Camera