Early January isn’t Puget Sound’s sweet spot, but when one is beholden to invitations to sail on other people’s boats, sometimes there’s no choice but to pack a few extra layers, a positive attitude, a piping-hot thermos and maybe something a little stiffer for après-sail time. So when an offer came to join some friends for an all-day outing that would involve a post-nightfall return (read: anytime after 1615 hours at 48 degrees north) to Seattle’s Shilshole Bay Marina, I packed my warmest gear and two FLIR handheld thermal-imaging cameras that I was testing, and I did my best to hoodwink myself into believing it wasn’t 27 degrees when we departed.

Flash-forward 12 frigid-but-fun hours and the sun had slipped below the Olympic Mountains as we were searching for a channel marker. I grabbed FLIR’s Ocean Scout 640 from my sea bag and, after adjusting color palettes, found the buoy just as things were getting frosty. Instantly, the mood thawed and conversation quickly pivoted to dinner, and a nip of Caribbean rum.

The desire to peer through the murk is as aged as the ancient mariner himself, and we modern cruisers are fortunate to live in times when off-the-shelf technology can significantly reduce the stress of nighttime navigation. While thermal-imaging cameras have historically been expensive, this equipment affords a huge amount of safety and situational awareness, both during daylight hours and on the graveyard watch.

Better still, prices are dropping. Here’s a look at how this technology works, and some observations gathered while field-testing three current-generation handheld devices.

Heat of the Moment

Thermal-imaging cameras sense minute temperature differences (read: thermal radiation) between objects and their backgrounds that are warmer than absolute zero (a balmy minus-459.67 degrees Fahrenheit). The cameras’ microbolometer sensors use what they capture to render video imagery.

For example, FLIR’s thermal-imaging cameras use microbolometers that are sensitive to 50 millikelvins, or one-twentieth degree Celsius, to create real-time video imagery, which is streamed to an integrated or networked display, requiring little user input. Much like digital cameras, thermal-image cameras come with different pixel densities; higher densities equate to higher-resolution imagery and better digital-zoom functionality (more on this later).

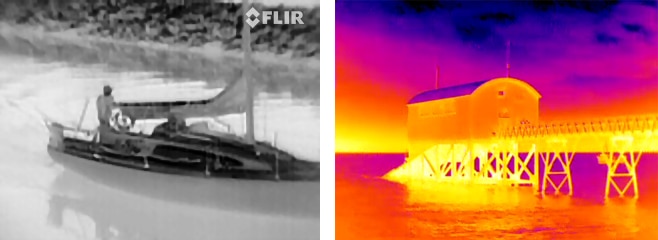

Most thermal-imaging cameras offer different color palettes (i.e., the set of colors that are used to render an image), which allow the users to tailor the imaging to different situations. When the right color palette is matched with the right atmospheric and viewing conditions, these palettes highlight areas of contrast. For example, FLIR’s Ocean Scout 640 handheld camera comes with three palettes, White Hot, Black Hot and InstAlert. “White Hot, where the hottest temperatures are white, looks best and interprets best at night,” says Jim McGowan, FLIR’s Americas marketing manager. “During the day, I like to flip to Black Hot, which is crisper when things warm up. And if you’re looking for crew overboard, InstAlert turns them red.”

Today’s manufacturers offer a wide variety of cameras, starting with handheld models that range from $600 to $7,000, all the way up to fixed-mount devices that can run anywhere from $2,500 to $85,000-plus.

Fixed-mount thermal-imaging cameras are fitted inside small domes that network with chart plotters or dedicated screens to display their imagery. These cameras are typically weatherproof, require little maintenance and can usually articulate their sensors along both vertical and horizontal planes. (Entry-level cameras sometimes only articulate vertically.) Also, all but one of the cameras mentioned in this article, both fixed-mount and handheld, offer digital zooms — optical zooms are only found on military-grade, cryogenically cooled thermal-imaging cameras — that enlarge each individual pixel to blow up an area of interest. “The better the resolution, the better the range and the sharper the image you can see,” says Tony Digweed, Iris Innovations’ director. “You can’t have one without the other.”

McGowan agrees: “Each pixel is capable of measuring a single temperature, which is the average of all temps across that pixel,” he says. “A small target like the head of a person in the water is going to be more distinct on a camera like the Ocean Scout 640, which has a total of 327,800 pixels, as it’s more likely to fully fill many single pixels, whereas on the Ocean Scout TK, which has a total of 19,200 pixels, a man overboard’s head is going to have more overlap with the surrounding water on the pixels that detect it. That means the average temp across those pixels will be lower, and the image will be less distinct until the camera gets closer to the target and the man overboard’s ‘hot-head’ target fully fills more pixels.”

While there’s no escaping the relationship between a camera’s image resolution and its effective range, manufacturers employ post-processing software to help enhance a camera’s detection capabilities. “It’s all about image processing and how it’s displayed on-screen,” says Digweed. Iris Innovations’ proprietary ICE software looks at the differences between pixels, and uses algorithms and firmware to draw sharper edges to help objects stand out against their backgrounds.

As mentioned earlier, fixed-mount thermal-imaging cameras can be networked to chart plotters or monitors to display and sometimes record imagery or perform other image-detection functionality.

FLIR’s new budget-minded fixed-mount M100 and M200 cameras are Ethernet-enabled and can network with any multifunction display that accepts video over IP. But when a camera’s paired with one of Raymarine’s new quad-core Axiom-series displays (FLIR owns Raymarine) the camera can identify potentially dangerous targets using FLIR’s proprietary ClearCruise IR Analytics. Once identified, the camera and the Axiom plotter collectively determine if the target’s speed and bearing represent a threat; dangerous targets are framed in bright yellow, and the analytics trigger top-level display alarms.

“The goal is to make the camera work for you, even when you’re not looking at it,” says McGowan, who compared ClearCruise IR Analytics to the automatic-radar-plotting-aid feature found on some high-end radars. Given the cost, most budget-minded cruisers will opt for a handheld camera, which is roughly the size of a beer bottle. “Handheld thermal-imaging cameras give you the flexibility to look around the rigging,” says McGowan, adding that handhelds are also ideal for dinghy trips ashore.

Much like their fixed-mount big brothers, handheld thermal-imaging cameras are typically built for outdoor use in the elements. Iris builds its devices to IP66 standards, and FLIR to IP67, which protects against immersion in up to a meter of water. Both rely on lithium-ion batteries charged by USB.

Higher-end handhelds come with a threaded tripod mount, as well as video-output capabilities. Also, some Wi-Fi-enabled chart plotters can wirelessly share their thermal-imaging feed with networked smartphones and tablets, and Iris Innovations’ new Xeye Pro app (Android- and iOS-friendly) allows its brand-new Xeye E3+ camera to stream thermal imagery to paired smart devices via Wi-Fi.

Picture This

To get a pulse on these cameras’ real-world performance, I borrowed three contemporary handheld thermal-imaging cameras for field-testing. These included FLIR’s (flir.com) budget-minded Ocean Scout TK ($600), FLIR’s Ocean Scout 640 ($3,500) and Iris Innovations’ (boat-cameras.com) Xeye E3+ ($2,695). I used them in both daylight and nocturnal hours at the same fishing pier at Seattle’s Shilshole Bay Marina.

Not surprisingly, the Ocean Scout TK, which offers a resolution of just 160 by 120 pixels, offered the least range and image resolution of the three cameras tested. That said, the Ocean Scout TK delivers seven different color palettes — Black Hot, White Hot, InstAlert Rainbow, Iron, Lava, Arctic and Graded Fire — and is also the smallest and most lightweight camera of the bunch.

Given that the Ocean Scout TK uses the same Lepton microbolometer that’s used in the company’s FLIR One ($250), which is a thermal-imaging accessory camera for smartphones, don’t expect to spot an overboard crewmember from any farther than 300 feet. However, the camera shoots still images and videos, which are stored on its 1.5 GB internal flash memory and can be easily downloaded via a USB cord. The Ocean Scout TK doesn’t zoom, but users can adjust the brightness, which, like the color palettes, can make a big difference. Overall, the Ocean Scout TK did a fine job of revealing close-in objects and buoys, but with only 19,200 pixels, range and resolution was a challenge, especially when one considers that a boat sailing at 6 knots will cover 300 feet in just 29 seconds.

The Ocean Scout 640 employs a significantly higher-resolution 640-by-512 microbolometer, allowing it to deliver higher-performance resolution and image clarity at all ranges. While the Ocean Scout 640 doesn’t capture video footage or stills — in that sense, it’s more of a scope — it offers composite video output, allowing it to be networked with a display, chart plotter or PC. The device includes a tripod mount and an LED light. Much like its less-expensive sibling, the Ocean Scout 640 uses FLIR’s proprietary Digital Detail Enhancement software to add image sharpness and allows users to adjust brightness. Unlike the smaller camera, the Ocean Scout 640 offers both a 2x and 4x digital zoom. In the field, the camera’s four InstAlert sensitivity levels give you a lot more control over tonal contrast than you would have with a single red-hot image-polarity mode. This made a big difference when trying to isolate individual crewmembers on passing vessels, picking out seals and sea lions or spotting people walking on a bonfire-strewn beach (read: lots of background heat) 0.4 nautical miles to the north.

Iris Innovations’ Xeye E3+ was the largest (by a small amount) and latest-generation camera tested. In fact, the camera I tried out was an early production model, and its 384-by-288-resolution sensor delivered impressive clarity.

The Xeye E3+ comes with four color palettes (White Hot, Black Hot, Red Hot, Iron-Bow), which are easily adjusted in real time, as well as a 2x and 4x digital zoom. However, the camera lacks a brightness control. Additionally, the Xeye E3+ comes with composite-video output capabilities (not to mention its bespoke smartphone app) and a tripod mount. The Xeye E3+ features an internal flash drive and the ability to record still and video imagery.

In the field, the camera delivered an impressive amount of definition, detail and image clarity, both in daylight and at night, at all ranges. While the Xeye E3+ can render an overall scene as well as its competition, its resolution allows the camera to reveal noticeably more detail. For example, when looking at a crowded marina-scape, the Xeye E3+ revealed boat names (decals absorb sunlight), boot stripes and even rigging details from hundreds of feet away.

While these cameras can be game changers — as I saw that cold January evening — all technologies have their limitations, including how they operate in rain and fog. “No thermal camera can see through water; it’s a camera, not a magic wand,” says Digweed. He adds, thermal-imaging cameras suffer when operating in “areas of low thermal differences and high humidity.”

McGowan advises that image quality in poor conditions can be improved if a user keeps the majority of the image sensor trained on the water, leaving just a sliver of reference horizon.

Irrespective of style or sophistication level, these cameras beat the heck out of squinting into the darkness on a frigid Puget Sound night, trying to spot a persnickety channel marker, rather than relaxing with friends.

– – –

David Schmidt is CW’s electronics editor.