Ever since publishing A Cruising Guide to the Lesser Antilles in 1966, I have been telling anyone who would listen that summer is the best time of year to be cruising in the Grenadines. During June and July, and often into August, the wind blows 10 to 15 knots day after day, seldom less and seldom more. Yes, it’s hurricane season, but if a tropical storm is forecast to head toward the southern end of the Caribbean, just sail south to Trinidad. And don’t stop in overcrowded Chaguaramas. Press on south to Pointe-a-Pierre at 10 degrees north, where you will be well south of the effects of any hurricane.

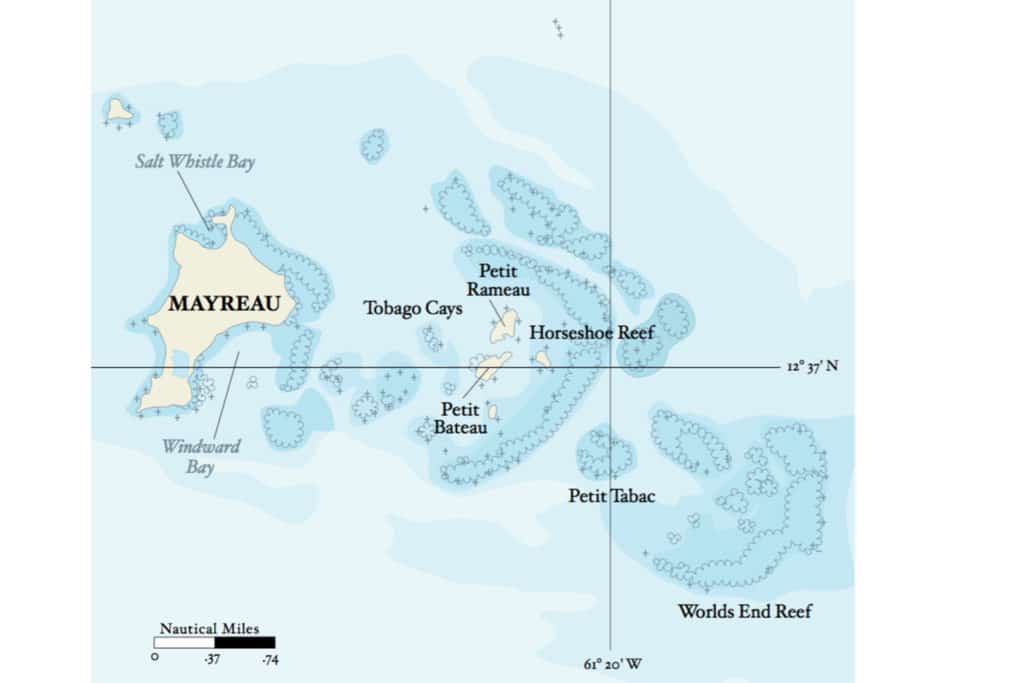

At any time of year, I recommend avoiding the overrated, overcrowded and expensive Tobago Cays. Other spots in the central Grenadines are just as spectacular, and nobody will force you to pick up a mooring. You might be alone in some anchorages or, perhaps, have the company of one or two other boats.

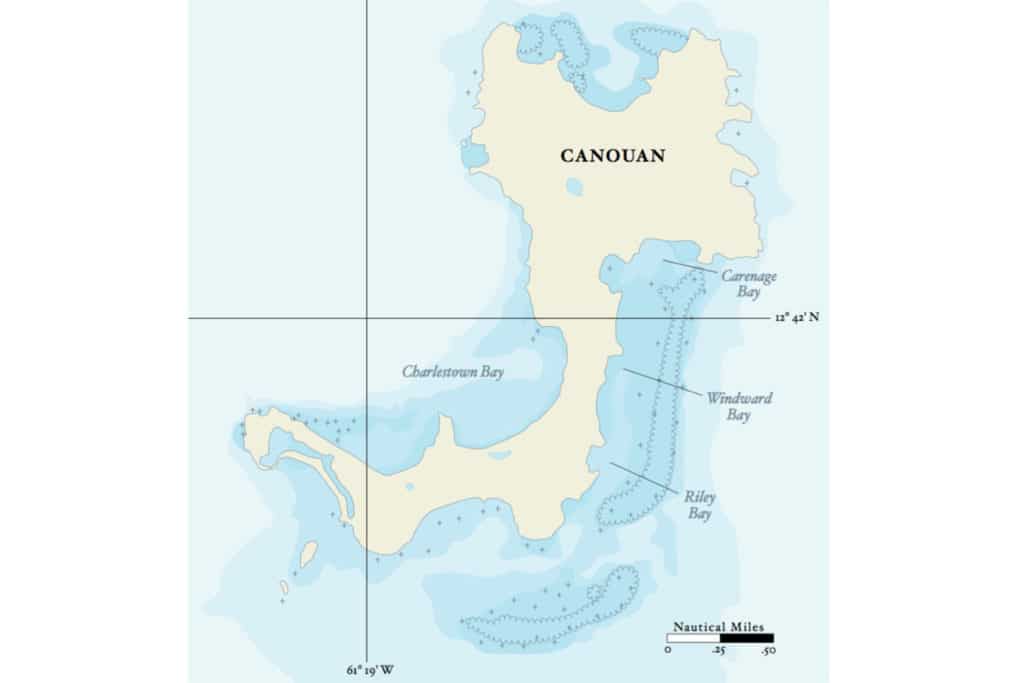

Boats heading south from St. Lucia or St. Vincent, whether on charter or bound for summer quarters at a lower latitude, will surely stop in Bequia. From there, skip Mustique and sail to Canouan. In the summer, the groundswell from the north isn’t a problem in Charlestown Bay, where the best anchorage is in the northeast corner by the coast-guard dock. If you’re looking for more of a challenge, the windward side of Canouan has a couple of anchorages.

Eastern Canouan

While I was cruising and exploring the central Grenadines in February 2015 with Geoff Curtain on Ariel, his Olympic 48 ketch, we were using the Imray-Iolaire B31 chart and discovered that it had errors, as do all the charts for the eastern side of Canouan. We threaded our way through the coral heads in Riley Bay, on the southwest corner of the island, and anchored at the south end of Windward Bay in 9 feet (shown as 2.7 meters on Imray-Iolaire charts). Windward Bay is 1 mile long and protected by a barrier reef, so there’s often a small chop in there but nothing more. We left the mizzen up to hold our bow into the wind because the sea comes over the reef and exits through the southern entrance, creating a southerly current 24 hours a day. We saw three small, perfect white-sand beaches that can only be reached by dinghy — the shore behind them is heavily overgrown and rises so steeply as to be impassable.

Contrary to the chart soundings, we found a full 8 feet (2.4 meters) of depth all the way to the north end of Windward Bay and also in Carenage Bay. The rock shown in Carenage Bay does not exist. (These and other corrections are on the 2015 edition of the chart.) There appears to be a channel, with a depth I estimated at 5 feet (1.5 meters), through the reef at Point de Jour at the north end of the bay, but I wouldn’t recommend using it.

Windward Mayreau

Another great anchorage is Windward Bay on Mayreau. The entrance is easy, but use eyeball navigation in good light, not your chart plotter. There is ample water and swinging room — after we anchored in Windward Bay, a 150-foot ketch came in and anchored in the upper bay. The crew loaded the guests into an RIB, exited Windward Bay through the 6-foot-deep channel in the northeast corner and took them around the island to the resort at Salt Whistle Bay. Geoff and I went ashore, walked across the low land and hitched a ride up the hill to the Catholic church, with its magnificent view. Below in Windward Bay, three boats were swinging on their own anchors. To windward, 50 or so boats in the Tobago Cays were swinging on moorings, paying fees to the park rangers and being bothered by boat boys trying to sell them stuff. We walked down the hill past numerous bars and restaurants until we found a quiet bar with no music, where we sat, admired the scenery, and enjoyed the beer and quiet conversation.

Kristian Nygard, of Nomad, tells me a sailor skilled at eyeball navigation can get into a good little anchorage tucked up behind its own reef in Petit Tabac, which is protected from seas by Worlds End Reef directly to windward. He reports 8 feet (2.4 meters) just outside and 6 feet (1.8 meters) inside. Here, you are guaranteed to be alone because two boats cannot fit into the anchorage, and you are within RIB distance — less than half a mile in semi-sheltered water — of Worlds End Reef, with its superb diving. If you dive here, or in other exposed areas, do so on a weather-going, or east-flowing, tide. (See the tides and currents sidebar.)

Petit Tabac is outside and southeast of Horseshoe Reef, which protects the Tobago Cays. While it is part of the Tobago Cays Marine Park, there are no mooring balls, and I very much doubt the park rangers will make the rough 1-mile journey out to Petit Tabac to collect their fees.

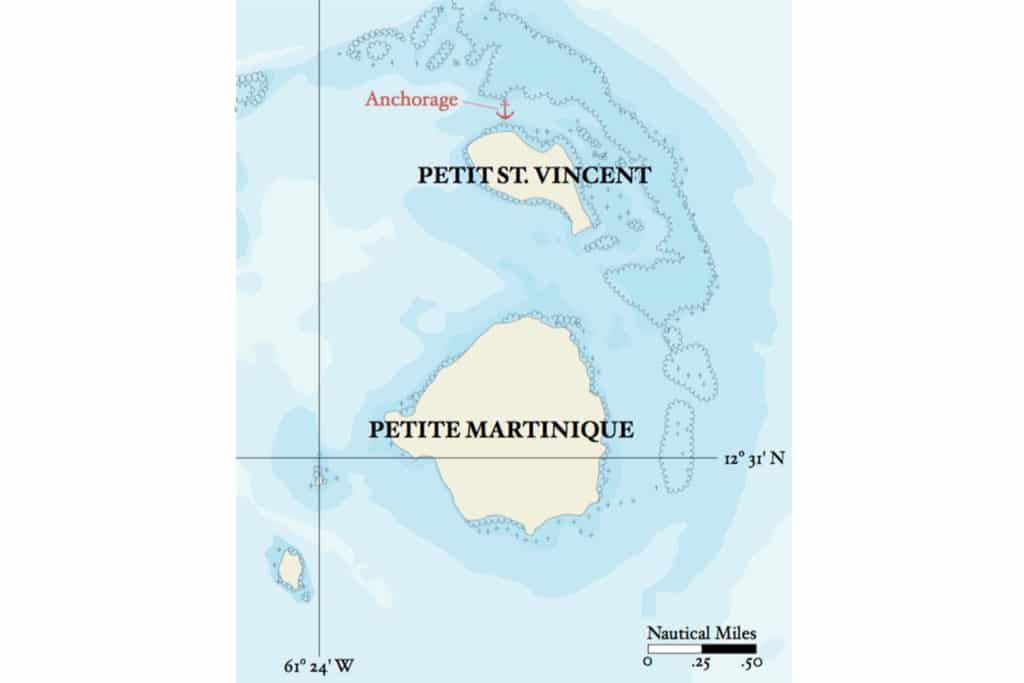

Sheltered Petit St. Vincent

Heading south from Petit Tabac, leave Palm Island to starboard, pass between the sand islets Mopion and Punaise, and head east into another wonderful sheltered anchorage on the north side of Petit St. Vincent, aka PSV. In the 1970s, this was a favorite anchorage of charter captains who wanted their parties to enjoy the privacy and good diving. You can go ashore on PSV, but on the beach only. The owners do not like sailors wandering around on their very private island, but public access to beaches — the queen’s chain — is a relic of British dominion.

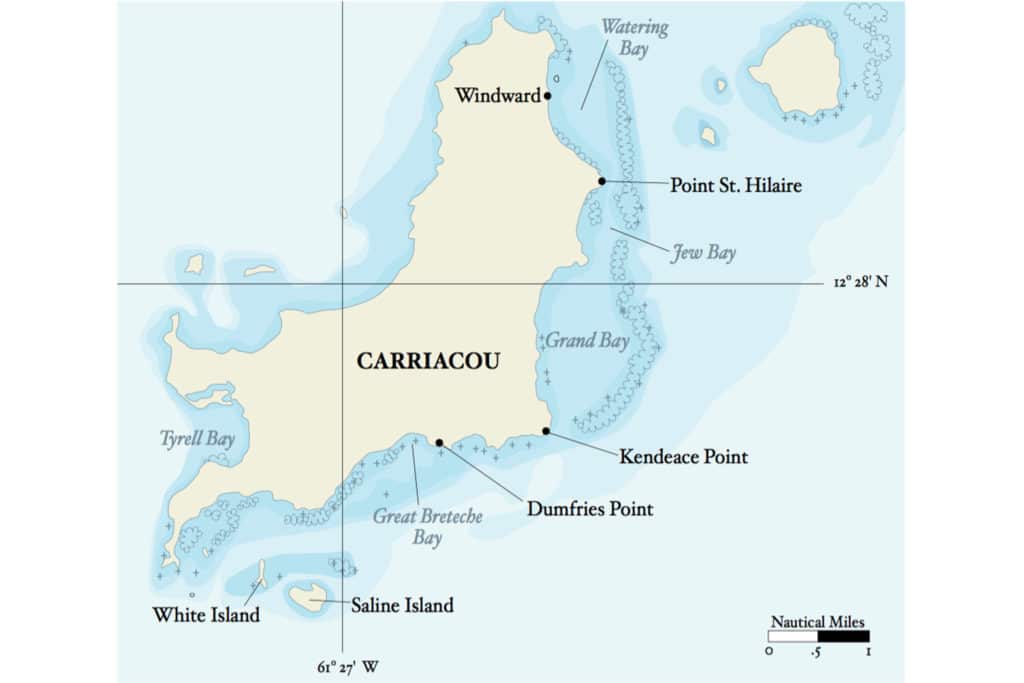

From PSV, sail north to Clifton, Union Island, to check out of St. Vincent waters, then south to Tyrell Bay, Carriacou, to check into Grenadian waters. The next day, explore the south coast of Carriacou, but don’t set out too early. Before 1100, the sun is too low in the east for you to navigate safely by eyeball when heading east along the south coast of Carriacou (or of any of these islands).

Carriacou’s Anchorages

Head southwest from Tyrell Bay 1.2 miles, round Southwest Point, and head east 4.5 miles along the south coast of Carriacou to Kendeace Point, the south entrance to Grand Bay. If you have time, you can stop along the way and anchor for the day and night off White Island. Andy Smelt, a sailmaker who has cruised the area for 30 years, recommends anchoring north of the island. He also says you can anchor north of Saline Island, but use a Bahamian moor there because the current reverses itself.

If you are good at eyeball navigation, the light is good, the wind is north of east, and you have the instinct to explore, take a look at an anchorage in Great Breteche Bay northwest of Dumfries Point. This is another anchorage that Nygard tested.

Kendeace Point marks the entrance to 4 miles of water sheltered by a barrier reef. Enter Grand Bay, tuck up behind the reef to anchor and enjoy some excellent diving. In the 1960s, Jim Squire would anchor the 55-foot steel schooner Te Hongi, which drew 7.5 feet, so close to the reef here that his charter parties would swim directly from the yacht to the reef without Jim having to launch the dinghy. (In those days, everyone carried dinghies on deck rather than towing them.) Jim would stay for two days, diving for lobsters and serving them to his charter guests for lunch and dinner. Grand Bay, Jew Bay and Watering Bay are protected by a 4-mile-long barrier reef. Sailing north, proceed with caution off Point St. Hilaire if you draw over 6 feet (1.8 meters). Eyeball your way by the point via the deepest water toward the deeper water farther north, but watch for the 2-foot (0.6-meter) spot in the south end of Watering Bay. Go slowly. The bottom is sand; if you stop, you are not aground, you are parked, and you will come off at high tide. (See the back of Imray-Iolaire B31, 2015 edition, for detailed piloting notes, including the ranges used by locals, provided by Kristian Nygard, David Goldhill, and Rex, a local fisherman.)

In Windward Bay, tuck up behind Crab Island, where the late Haze Richardson, the former owner of PSV and a registered preacher, conducted weddings. Then go ashore to the settlement at Windward where, with luck, you’ll see a local sloop being built or repaired. You might also be able to buy some Jack Iron rum, which has such a high alcohol content that ice cubes sink in it.

Remember to take into account that the sea level in the Caribbean in June and July is usually about 18 inches lower than it is the rest of the year. David Goldhill, who has lived on the windward side of Carriacou and sailed Grand, Jew and Windward bays since 1984, reports that a tidal anomaly occurs inside the reef at spring tides coincident with the spring and fall equinoxes. At these times, the tidal range inside the reef can be as much as 3 feet.

Grenada South and East

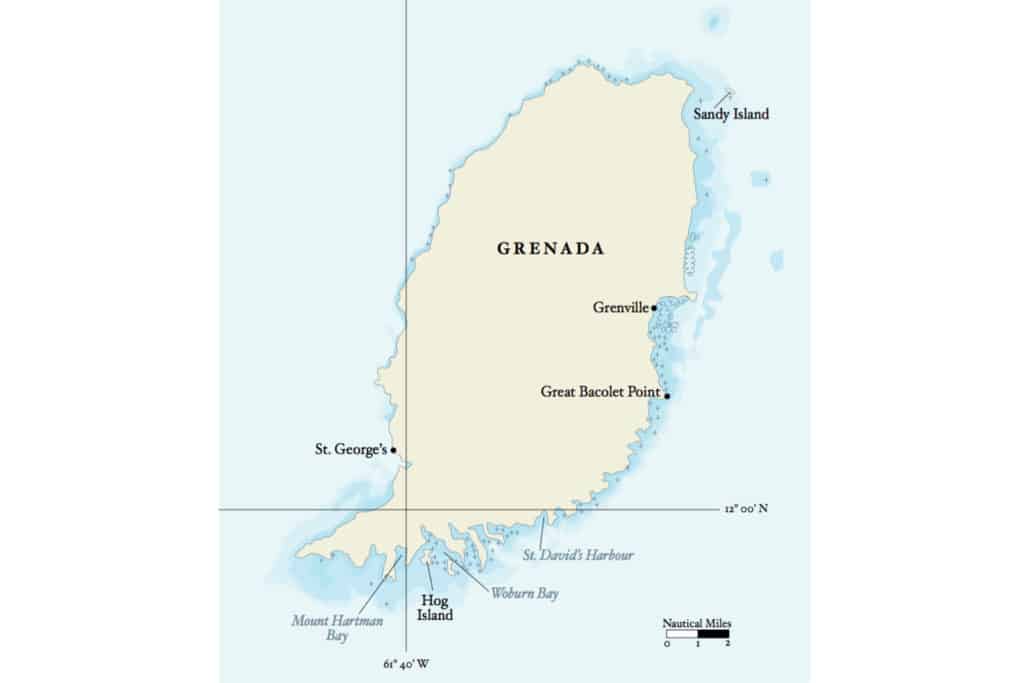

Since you have already cleared into Grenadian waters, when you have finished your stay in Windward Bay, head south down the windward coast of Grenada on a glorious beam or broad reach, depending on the wind. Continue south on port tack until you can jibe over to starboard and approach the entrance to Woburn Bay (also known as Clarkes Court Bay) on a northwesterly course. Once you arrive within a mile of Calivigny Island, forget about your chart plotter and eyeball your way into the harbor. Do not trust, or become confused by, the buoyage on the south coast of Grenada. Anchor in Woburn Bay and explore the area by dinghy. Go west to the Hog Island anchorage and Mount Hartman Bay, or east, passing between Calivigny Point and Calivigny Island to visit Le Phare Bleu Marina, and on to Egmont Harbour. From your anchorage in Woburn Bay, you can visit five restaurants and a dozen different bars by dinghy. From Woburn, at the head of the bay, there is good bus service to St. George’s.

From Grenada, North

If you are in Grenada waiting out hurricane season, instead of sitting in the same spot until you are aground on your own coffee grounds, take advantage of the fair winds and head north to Carriacou for a change of pace. This is a good time of year to explore the east coast of Grenada along the way.

At 84, I am still exploring, and in November 2014, I chartered a dive boat. Armed with a handheld depth sounder, I went in search of new anchorages on the south coast of Grenada and checked on the status of others. As a result, I made several corrections to Imray-Iolaire Chart B32. Until the chart is reprinted, those corrections are posted on the Imray website.

A new anchorage I discovered is south of Great Bacolet Point, only 10 miles, or a morning’s sail, from Clarkes Court and Woburn Bay. From St. David’s Harbour it’s only 6 sailing miles.

Since in summer the wind will usually be south of east, take off from Clarkes Court Bay early, about 0700, and stand out on port tack for 3 miles, then tack back. Enter from the southeast, heading northwest. If a swell is running, the 8.8-foot (2.7-meter) shoal on the north side of the entrance course will be breaking. If the swell is not breaking, it will hump up over the shoal and will be easy for an eyeball navigator to spot. The harbor shoals from 30 feet (9 meters) to 20, then to 10 in the inner harbor, where it will be calm.

The next day, take a short port tack out to sea until you can clear Great Bacolet Point on starboard tack. From Great Bacolet Point, it is a close reach 3 miles north to Grenville or 10 miles to Sandy Island off the northeast corner of Grenada.

Grenville is not as difficult to enter as sailors think. The sea buoy is there, and although the turquoise house marked on the chart has been repainted and is hard to spot, the directions on the back of Imray-Iolaire B32 will pilot you between the two coral heads in the outer channel and in toward Luffing Channel.

The anchorage in Grenville is sheltered from the sea but not from the wind. It is a great place to windsurf or kitesurf, or just swim and relax. You can rent a car or hire a taxi to visit the Belmont plantation and River Antoine Rum Distillery, where cane is crushed by a water wheel, and then on to the chocolate factory.

Alternatively, it is only 10 miles on a close-reach course from Great Bacolet Point to Sandy Island. In the late 1950s, developers began construction of a resort on this beautiful uninhabited island. Large buildings were built, but the project died. Anchor on a Bahamian moor here, as there is a reversing tide.

For the passage to Carriacou, calculate when there will be a weather-going tide and take advantage of it so you don’t get set to leeward of the island. It’s 15 miles from Sandy Island to White Island, or 17 miles to Kendeace Point. With the weather-going tide, you are guaranteed a nice fast reach (if there is wind).

Do not waste July, August and September sitting at anchor worrying about hurricanes. Go sailing! If a tropical storm threatens to approach the southern Windward Islands, head south. It’s only a day’s sail from the Grenadines to Grenada, and another day (or night) to Trinidad.

Caribbean Tides and Current

The predominant water mover in the eastern Caribbean is the Equatorial Current that sweeps across the Atlantic Ocean, driven by the trade winds. Squeezed into the passages between the islands, it accelerates. The flood tide flows against it, at times overcoming it, and the ebb tide flows with it, often boosting it to 2 knots. When sailing north, and also when diving, it pays to have the tide flooding toward the east. Don Street, with help from longtime residents in the islands, has it mostly figured out.

Think of this as a homework assignment. On the back of the Imray-Iolaire charts you’ll find all the information you need to calculate the times of high and low tide, except for one piece: the time of meridian passage of the moon. This missing piece is published every month in the Caribbean Compass. (It’s also in the Nautical Almanac.) Your interisland passages will be much faster, especially when you’re northbound or eastbound, when you can use the tide to your advantage.

This article first appeared as “The Grenadines of Summer” in the January/February 2018 issue of Cruising World. Author Don Street has been discovering anchorages in the eastern Caribbean since 1956, when he purchased Iolaire and began using her keel to locate the 7-foot soundings contour.