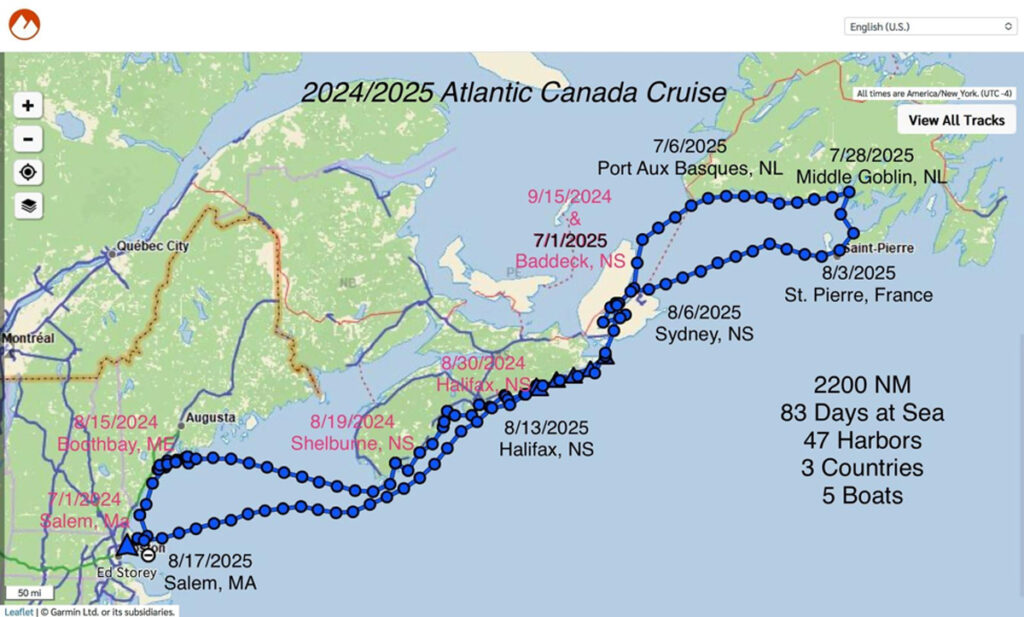

The Blue Water Sailing Club’s (BWSC) Atlantic Canada Cruise 2024-2025 (ACC) was an unprecedented undertaking, a first of its kind in the club’s history. Four vessels—Going Merry (a Hallberg-Rassy 42), Grayling (Sabre 38), Truant (Southern Cross 31), and Avocet (Oyster 41)—set out from Boothbay Harbor, Maine, on August 15, 2024, immediately following the annual “Maine Cruise.” Despite the varying capabilities of the boats and the diverse experience levels of their captains and crews, not one captain had previously sailed their boat north of Halifax. The fleet was later joined by a fifth boat, Walkabout (a Sabre 38), in Baddeck, Nova Scotia, in June 2025. The expedition eventually concluded for Avocet in Boothbay Harbor on August 17, 2025, after a 49-hour sail from Halifax (Rogue’s Roost).

Truant was single-handed, more often double-handed and occasionally had three onboard. With a 25-foot waterline, Truant proved that many of our smaller BWSC boats, if sailed by inspired skippers, can manage this trip. Typical daily mileage was limited to usually not more than 25 nautical miles—and often considerably less daily mileage than previous Club trips to Nova Scotia and the Bay of Fundy. Alternating lay days and short legs appealed to many participants.

A number of things made the trip unique for the Club. The cruise was long. We sailed 2,200 nautical miles. We were at sea for 83 days. We saw 47 harbors. It spanned two summers. We went to three countries.

The Atlantic Canada Cruise (ACC) was an expedition-type club cruise. There were three overnight passages. The last passage (284 nautical miles) had two back-to-back overnights. Matinicus to Shelburne, N.S., St. Pierre to Sydney and Halifax to our various homeports. These passages made possible a detailed exploration of the Atlantic Coast of Nova Scotia, the Bras d’Or Lakes, the southern coast of Newfoundland including many of its magnificent fjords, several of the islands along Newfoundland’s southern coast including Burgeo and Ramea, and the French islands of Miquelon-St. Pierre.

Days off the boats were spent exploring these harbors and hiking in some really spectacular places. We were greeted warmly and with much curiosity everywhere—though many places were without a population or road access.

One fellow in Rose Blanche, eager to show us his way of life, took a few of us jigging for cod. The catch fed the entire group. These were fish you hook as soon as you drop the hook. So, we got equipped. In the fjords, birds perched high in the surrounding cliffs were answering my son’s cellphone bird-identification app. It was acoustically as impressive as listening to a concert in Carnegie Hall. And very remote. Our hiking teams, often exploring simultaneously different ridges, took handheld radios as help could only come from the anchored boats. Much of this was captured by Homer, which was our squadron’s only drone after the loss of its sister drone.

Nature was front and center. A small group of pilot whales repeatedly crossed within feet of our bows in 5- to 6-foot swells en route from Piccaire (Pink Bottom) to Brunette Island, Newfoundland. This was a different behavior than what I have seen crossing Georges Bank where larger groups of whales have flanked Avocet on both sides as if in a convoy. This was purposeful and playful activity by very large mammals. To finish that day at anchor at Brunette Island (en route to Fortune, Newfoundland), locals came over in their skiff, chatted it up, asked where we were from and gave us a bag of their freshly harvested scallops. They were the best scallops I have ever eaten. Caribou were grazing unperturbed on a hill in front of us at this spot. No roads. No bridges. No light pollution. Virtually no people. A few fishing huts. Elsewhere others in our group were given jars of moose meat and moose sausage. A delicious and unexpected appetizer for the group. Tasted like flank steak. Coming off the sea we were not quite tourists nor were we mere transients. The relationship was one of mutual interest and respect; we shared the sea. They were as curious about us as we were of them.

The composition of participants was another somewhat unique feature. For only five boats, there was an extraordinary number and mix of people of various ages, occupations and familial relation. By one estimate, 50 folks sailed various parts of the trip. Nine married couples. Three sets of brothers. Two sets of brother-sister pairs. A son. Cousins. Uncles. High school buddies. College buddies. New BWSC members. Old sailing friends. New relationships were made and old relationships were nourished. The different types of sailing permitted (and sometimes required) different sets of crew along the route. The number of participants coupled with the remoteness of many of our crew points in Newfoundland and parts of Nova Scotia added complexity to our crew changes and fresh faces to different legs. There was also continuity in the group. For three of our original four boats, many who crewed in 2024 returned to crew in 2025. One returning non-member crew sailed on two different boats.

The trip was organizationally unique. We were graciously given a pass by local Customs authorities in advance in regard to the statutory importation tax in Canada and departure requirements when overwintering. Canadian Customs officials have wide discretion. We also scheduled a departure from Canada and into France (St. Pierre) so as to re-new the one-year limitation period for Canada on re-entry. As it turned out, Customs would have granted us more than a year to clear out had we needed it. We were apparently deemed to be trustworthy guests.

The trip required a broader set of seamanship skills than our Club’s typical two-week cruises. These skills applied mostly to mechanical issues. One boat’s windlass fell through the deck and had to be re-bolted. Another boat’s windlass had electrical corrosion issues. An AIS transmit function required electrical work to get functioning.

The AIS transmit is an important safety capability when traveling at night and/or in the fog and especially in a group of boats. It is also handy when port authorities are trying to locate and manage your approach in no visibility conditions such as what we had going toward Port aux Basques. With lots of other traffic, there is not a lot of time for the traffic control officers to be plotting your exact position by digesting lengthy lat/long numbers given verbally over the radio.

Three engines had oil changes, which, in turn, unveiled a potentially serious issue relating to the exhaust system and decomposing air filter in one of our boats. A toilet pump in one of our boats required a call for tech support and an on the spot rebuild. In Burgeo, a boat’s anchor got stuck on a submerged pipe. To jimmy it free, a secondary trip line was secured and then winched from another boat’s primary. One boat developed engine starting issues relating to fuel intake. This was addressed eventually at Baddeck Marine as was another boat’s complete repower. There was also a transmission issue that was addressed on the fly.

Baddeck Marine is a wonderful place to winter over if you do the decommissioning work yourself. The yard forgot to winterize Avocet’s fresh water system. All plumbing fixtures, hoses and filters were replaced at the yard’s expense and without discussion. They are honest, friendly and hard working folks. Every yard makes mistakes. Not every yard covers the costs of those mistakes. Their rates were extremely reasonable. The town of Baddeck is on the Cabot Trail and is therefore a great place to spend the time necessary when hauling or launching.

The greatest perceived challenges turned out to be largely overblown. Anchoring was not a problem though heavy ground tackle was necessary. One boat upgraded their gear for 2025. Another boat passed on a few anchorages. Rafting up, splitting up, and/or tying stern to shore resolved matters in the few places that were tight. In Pink Bottom, three boats rafted up with a stern line and the other two boats moved on to alternate anchorages. More boats could have easily joined this trip.

Katabatic winds and fouled anchor rodes, referenced by Paul Trammell in his book, Sailing to Newfoundland: A Solo Exploration of the South Coast Fjords (2023), were never a problem—however Mr. Trammell, a newcomer to sailing, deserves all the credit for undertaking such a remote trip solo. Brave man. And without a windlass! He used an InReach device for tracking when he hiked.

Our group did have to hold position an extra night at anchor in Yankee Cove, Nova Scotia, in 2024 as we were in an extended small gale. In Francois, Newfoundland we tied to a dock for the night in winds which a local told me were gusting 60 to 65 knots. The wind was greater than I have previously experienced. This local fellow correctly advised before the wind hit that it would be pushed from the North to the Northwest by the cliffs—and he was correct.

Along the fjord coastline and in front of all the cliffs, this was a dangerous lee shore very close alongside and on our rhumb line heading east. On the most egregious day, only Truant (with my son aboard) took the conservative action and gained significant sea room. It would have been difficult to impossible to sail out of trouble had there been engine failure. Anchoring was not an option as water depth close to shore was too deep. This was an instance where sailing in a group actually added a measure of hope if not real safety since we had Going Merry and her 60-horsepower engine in close proximity for a tow.

There were similarities between the Nova Scotia and Newfoundland trips. Both areas are thinly populated and are stunning in physical beauty. Both summers had extraordinarily good weather: sun, little fog and almost no rain. There was so little rain in 2025 that Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, was under a no-campfire ban. At Liscombe Lodge in Nova Scotia folks were not permitted on the hiking trails. Warm air (cool nights) and warm water (in places). Bugs were not as bad as predicted. Provisioning was a snap. Canadians freely drove us around or lent their cars and trucks.

Differences between our Nova Scotia and Newfoundland trips were not immediately apparent in advance. We sailed Nova Scotia over 70% of the time. This sailing to motoring ratio was reversed in Newfoundland because of short, steep and confused swell in the Cabot Strait and along the southern coast. The Labrador Current, the Gulf Stream Current, the Atlantic Ocean Current and enormous fetch coming up against the cliffy fjord sections of Newfoundland created convergence, blocking, gap and funneling effects. Truly a bad combo. Leaving mid-August for Nova Scotia from Maine proved to be correct for better wind and less fog. Sailing west to east along the southern coast of Newfoundland (from Port aux Basques and Squid Hole to the Lampidoes Passage) was critical. Waves, wind and current were all against us if going the other way.

Entering and exiting Dingwall, Nova Scotia, was uneventful at high tide for Avocet. She draws 8 feet. Exiting Ingonish, Nova Scotia, was not so good. A narrow channel blocked by a lobster buoy in the middle offered a 50-50 choice—she bumped the bottom but got kudos for taking one for the team following astern. Another advantage to sailing in a group.

In two of the Newfoundland fjords (Hare Bay and Facheux Bay), fish farms combined with unrelated, very long, singular, and haphazardly placed floating lines made navigation sufficiently difficult to require assistance from the boats tending these farms. At night or in fog, these areas would be arguably non-navigable. Our group relayed this information to those behind. We closed quarters and filed through in a single row.

Our group of four boats sailed as a group in Nova Scotia in 2024. Our group of five boats in 2025 sailed as a group in Newfoundland. On the return from St. Pierre, France (8 nautical miles southwest of Newfoundland), decisions had to be made sailing against prevailing southwesterly winds and the group split. One group headed to Sydney two days ahead of schedule to catch favorable conditions on that overnight passage. One boat in the other group had a schedule to meet in Sydney; and, joined by another boat, departed St. Pierre on schedule but two days after the first group. This second group subsequently departed Sydney three days after the first group. One boat hauled for the winter in Baddeck. Another boat chose an accelerated route and schedule home. In Halifax, where three boats were joined, captains read the weather differently, as they did in St. Pierre, and made departure decisions accordingly.

It is essential in sailing passages that weather windows are paramount and that each captain makes his or her own departure choices. Crew meetings in both St. Pierre and Halifax were structured to ensure that this protocol was followed. This is not what happens in organized ocean races where a race committee makes the starting gun decision for the fleet. Although it is true that our group saw different things in terms of the forecasting, it is equally true to note that this was essentially a near coastal return where safe harbors are relatively close at hand. For this reason, a weather router, like Chris Parker, was not used though he did speak for us in a 2023 seminar on the trip.

For the Blue Water Sailing Club’s “CCC” (the Caribbean Challenge Cruise 2026-2027), the stakes are higher sailing Newport to Bermuda in November. Using Chris Parker will be helpful to everyone regardless of experience levels.

Although our captains could have called in their own weather router, they relied on their own resources, heard from all other captains and learned from the experience. Weather models do not always agree with each other. Without hands-on experience doing the weather routing part and sailing a few overnight passages, one has a disadvantage relying solely on another person’s opinions and advice.

What did I learn as trip leader? It is more fun to sail in a group.

If I were to do the trip again with the same northerly winds some of us enjoyed sailing south from St. Pierre, I would sail straight to Louisbourg and skip Sydney. Sailing home in prevailing southwesterly winds requires one to be opportunistic whenever there is a northerly component. Chris Parker, prior to this trip, put it starkly. It is easier to sail from Newfoundland to Bermuda than it is to sail Newfoundland to New England.

Louisbourg gets you farther south and is more direct than going through the Bras d’Or Lakes and St. Peter’s Canal. Sydney has about an 8-mile slog up the harbor which is long, out of the way; and it comes after an overnight passage. Baddeck is not a port of entry. Sailing to Louisbourg does mean that your crew skips the Bras d’Or Lakes, but our group of boats sailed the lakes in 2024 going to Newfoundland. The lakes are a thing of beauty—not to be missed. As awesome in their solitary splendor as the fjords in Newfoundland.

On the return along the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia, Avocet adopted several strategies. Sail early before the southwesterlies pick up, go short and stop early, and make more stops. Sail the rivers and inland bays on a beam reach like Country Harbor, Tor Bay (Webber Cove) and the beautiful and navigationally entertaining inner passages like Dover Island Passage. No rush.

The key to my kind of sailing is to find a way to do it all in cool, new places with the right mix of gunkholing, offshore passages and local exploration and to do it slowly, often with significant breaks in the action, with the right crew, friends and family. This trip has now introduced me to club cruising and it has elevated the experience. Those who join are like-minded folks who are excited about going. Hopefully, they have chosen the parts of the trip they will like. It is more rewarding to share it than it is to go solo.

About the Author: John Slingerland sails out of Boothbay Harbor, Maine on his Oyster 41, Avocet. A graduate of Middlebury College and a retired lawyer, he is presently Commodore of the Blue Water Sailing Club. John has recently completed a four-year circumnavigation of the North Atlantic Ocean and Western Mediterranean Sea. He has since led Blue Water Sailing Club members to Nova Scotia and Newfoundland. Click here for information on joining the Blue Water Sailing Club or participating in its upcoming sailing adventure to the Caribbean. The Caribbean Challenge Cruise leaves Newport, Rhode Island, in November 2026 and returns from Grenada, via Sint Maarten and Bermuda, in April 2027. Review the short form itinerary and register for the trip here.