It’s been nearly seven years since we sailed our Stevens 47, Totem, into Richards Bay, South Africa, for the three-month stay that would give us a fondness for this beautiful, complicated country. We’re back again—the “expedient” way, by plane instead of sailboat. We endured diverted and canceled flights, hours in airline customer service lines, and all our checked baggage going missing. It took longer to travel to South Africa by sail, but the food was superior, and all baggage was accounted for.

Both trips proved bumpy at times. I don’t know about our Boeing 787 pilots, but in 2015, the crew of Totem employed all the tools from our weather toolbox, and added a few new ones, to sail safely to southern Africa. Tools include GRIB forecasts (which require good interpretational skill), a meteorologist’s text-based forecasts, tide tables, synoptic weather charts, pilot charts and cruising guides.

These tools are also entirely inadequate for some types of weather that can ruin a cruise quickly. To make the point, consider the humble chubasco.

What’s a chubasco?

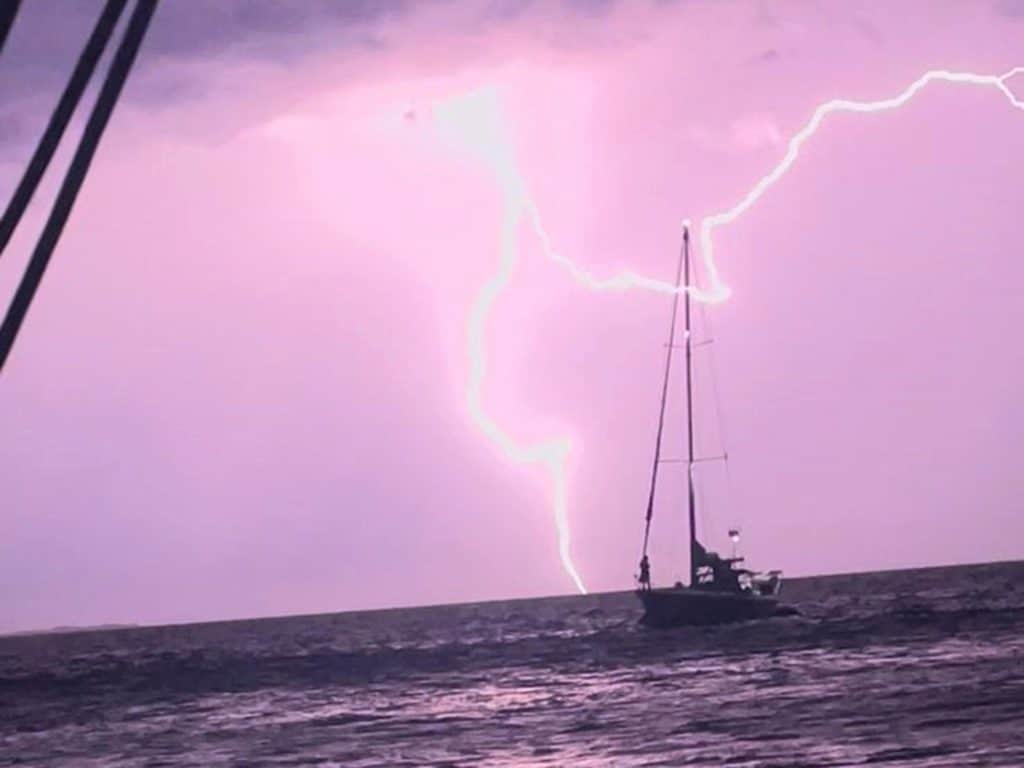

Hardly known outside of Pacific Mexico and Central America, a chubasco is simply a thunderstorm—or, to the sailor, a squall. But it’s a doozy of a squall, and there’s nothing simple about it. A chubasco is a violent area of intense rain, lighting and wind. For cruisers in the Sea of Cortez in July, August and September, it’s essential to learn about chubascos.

They start (mostly) as thunderstorms formed by air heating in the afternoon over the Sierra Madre mountains, along the east side of the Sea of Cortez. The thunderstorms may dissipate, or head across the water toward Baja as chubascos, on a collision course with northern anchorages that cruisers favor during hurricane season. And, the chubasco’s arrival is somewhere between “oh-dark-thirty” and “wee hours of the morning,” not anyone’s finest hour to jump out of their bunk and into sudden, severe conditions.

These little weather bombs are nothing to mess around with. We’ll never forget our first chubasco: anchored off Bahia de los Angeles in 2009. Late one steamy summer night, the chubasco clocked 70 knots and blew up our neighbor’s wind turbine.

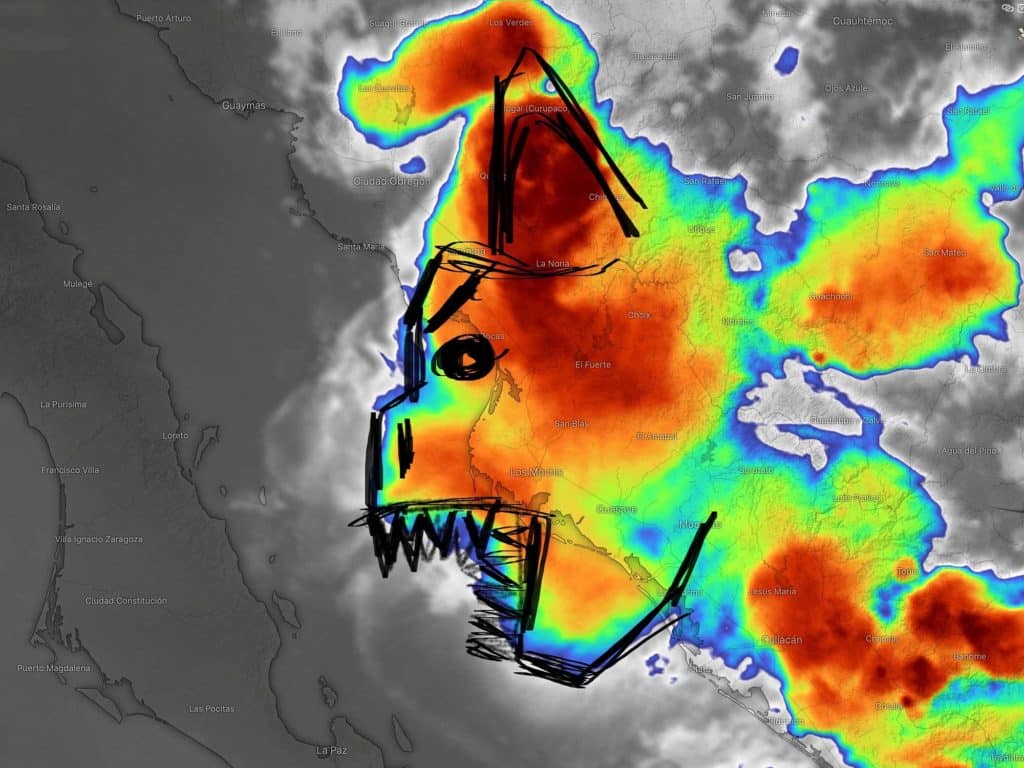

Our cruising friends recently captured the drama of a chubasco. At a favorite midriff island in the northern Sea of Cortez, crew of the Gulfstar 50 Alegria snapped Marga Pretorius’ Kelly Peterson 44, Dogfish, across the anchorage during some chubasco drama.

What forecast tools show chubascos?

Of the forecast tools mentioned, not a single one will indicate that a chubasco is headed your way. So, what can cruisers do?

During our summer 2009 in the Sea of Cortez, not much. We’d simply choose to avoid exposed anchorages (or accept the risk) during peak season.

Even today, with dramatically better weather tools, what we typically use as cruisers doesn’t anticipate chubascos. Rain and cape elements of GRIB forecasts might show thunderstorms forming over Mexico or along the coastline, but they don’t show where the chubascos are headed, or how long they’ll last.

The chubascos might fade in place. Or, a chubasco spanning the 50 to 100 miles can be mild, with 25 knots of wind and rain. (A baby chubasco, a chubacca!)

But the chubasco can also be several hours long, packing winds of 50-plus knots. It’s the kind of weather cruisers want to know about before it hits.

Satellite imagery for chubasco forecasting

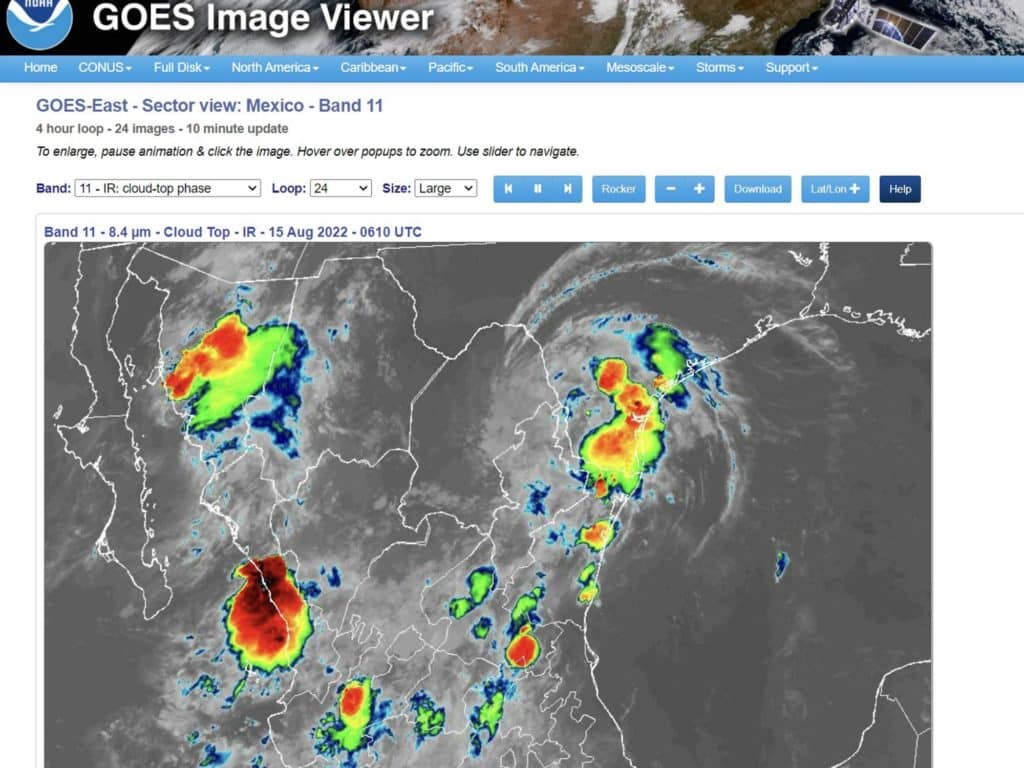

GOES band 11 is a product of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Its stated primary purpose is to monitor volcanic activity, but it has an infrared (visible day and night) view of cloud tops over Mexico. When that view is set to a loop, it shows the intensity and movement of the thunderstorms that become chubascos.

Being able to see big, red blobs moving toward Baja is the only technical knowledge necessary to use this tool. It’s enough to make good anchorage choices for the night. Cruisers can look at GOES imagery in the afternoon and early evening to assess risk in their location. No red blobs to the east? Low risk of a chubasco.

What influences the probability of the blobs coming across? Cooler water temperatures (below 80 degrees Fahrenheit) lower the risk. So do moderate or strong surface winds from just about any direction but east.

We’ve been in the Sea of Cortez aboard Totem for part or all of five summer chubasco seasons. During the first season, 2009, satellite imagery like GOES wasn’t available. Every night, we anchored in a place with easterly protection, just in case. In later years, with satellite imagery, we could stretch out to other anchorages. When the big red blobs threatened, we moved.

Accessing these products requires internet connectivity. There are only a few cell towers in the northern Sea of Cortez, but it’s possible to stay dialed in. Alerts are shared among cruisers in a nightly text-based email, and Starlink satellites have made many previously disconnected parts of the sea more accessible.

Chubascos may be livening things up more than some of us wish (here’s the video clip that the photo of Dogfish came from; you can see Marga on the bow of her boat). But weather is also just another day in the life of cruising, a trade-off we make to enjoy this beautiful corner of the world.

Like chubascos, many other localized winds we’ve experienced come with names: bullet winds in Papua New Guinea, the Sumatra in Indonesia and Malaysia, the Papagayo in Nicaragua, the Santa Ana in Southern California, the coromuel in Mexico, and the southerly buster in South Africa and Australia. Some are easily forecasted. Others, less so.

Adding creative, less-common tools to the weather toolbox improves predictability, whether we’re on passage or at anchor.

Further Chubasco resources:

- The Sonrisa Net has a great Chubasco overview

- Ask a cruiser on the Sea of Cortez about “Jake’s Famous Cubasco Report” for a nightly email warning, or read Jake’s most recent chubasco forecast online