Hope sailed east across the North Atlantic in the stable evening conditions about 600 miles from St. John’s, Newfoundland, Canada, a third of the way to Dingle, Ireland. Skipper Michael Leland, a retired orthopedic surgeon from Valparaiso, Indiana, was in a state of Zen, preparing another magical meal in the galley using containers of various ingredients — most of which I’d inventoried before leaving Newfoundland and listed as “unknown: twigs, seeds and floor sweepings.” Michael’s magic in the galley complemented the spirit of the open sea.

Wafting upward among the aromas from the galley below came another unbelievable proclamation attributing some great social credit to Michael’s ancestors, the Vikings. Not as grandiose as inventing fire, as he attested, but nearly as improbable. Within moments, one of us called out, “Bullshit.” I missed Google in the middle of the ocean. With four guys — three of whom were solo sailors — on a 32-foot sailboat without access to Google, it was impossible to verify the increasingly fabulous tall tales of unreal accomplishments. On the good side, this made for lively conversation during the evening meals.

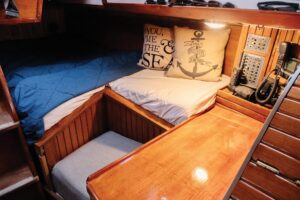

Hope is a Najad 332 built in Orust, Sweden, in 2005. She was thoughtfully modified to fulfill Michael’s lifelong dream of sailing his own boat to his Norwegian homeland via the great routes of his Viking ancestors. Following Hope‘s wake backward, she spent her first eight years on the Great Lakes, sailing, racing and preparing for this adventure. Stepped with a taller carbon mast to take advantage of the light winds common in the summer races on Lake Michigan, she was a lively boat, and easily managed when the sail plan was reefed. Additional modifications included desalination, critical navigation electronics, communications, solar panels, a hydro generator, autopilots (both electronic and a windvane), a short bowsprit for flying asymmetrical chutes and a step platform at the mast to safely elevate the crew working on the mainsail.

Following Michael’s retirement in 2015, Hope was shipped to Jamestown, Rhode Island, where Michael and crewmembers Vik Warren and Moose DeBone sail-tested her on Narragansett Bay before sailing up and down the coast to Nova Scotia, Canada, and back to enhance their ocean skills. In May 2017, after wintering at the Jamestown Boat Yard, Hope was relaunched and prepped, over a week of sailing, for departing on the first legs of this multiyear, round-trip Viking passage.

The planned route began in Jamestown, with crew Bruce Carter, Moose and Michael sailing to Halifax, Nova Scotia, and then on to St. John’s. In St. John’s, I joined the crew as we convened on August 1 to cross the North Atlantic to Dingle. From Dingle, the route would continue around southern Ireland to Howth, near Dublin, and then up the Irish Sea to Fort William at the start of the Caledonian Canal to cross the top of Scotland. From Inverness, on the east coast of Scotland, we would sail the North Sea to Mandal, Norway, and then on to Hope‘s birth home of Orust to winter over.

After the mandatory shutter clicks and the topping off of fuel, Hope slipped her lines at the Royal Newfoundland Yacht Club and headed east on the quiet waters of Conception Bay. Sailing enthusiastically slow in the light evening airs set a perfect transition to life at sea. As night fell and lights twinkled on the last points of land fading behind us, a fair breeze caught us as we slipped into our watch system.

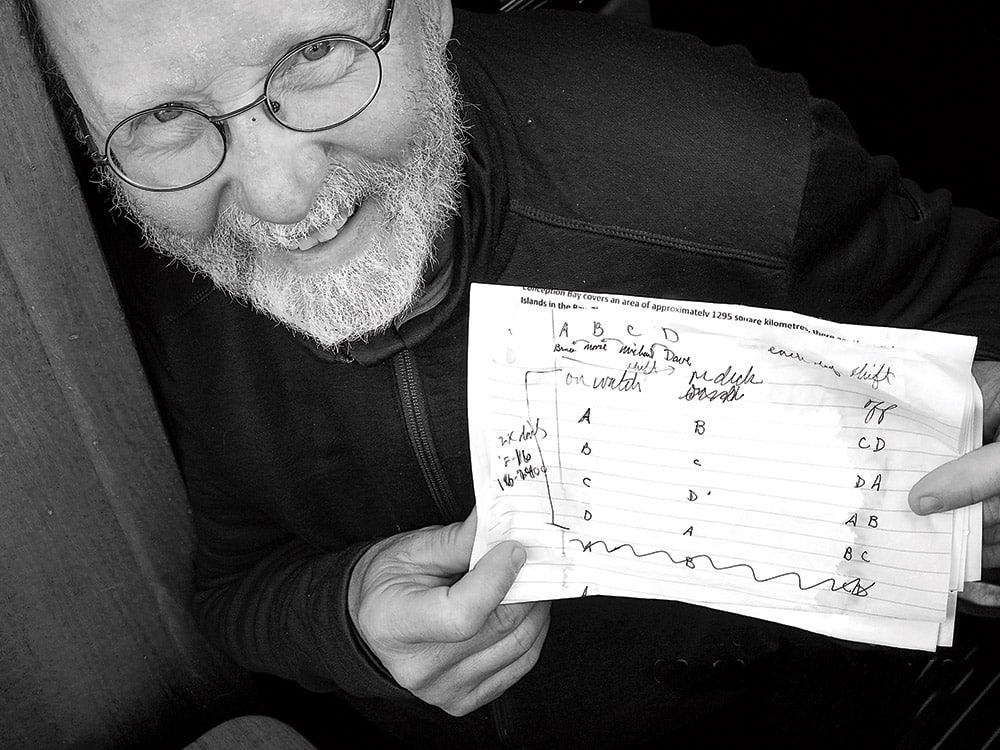

The watch system consisted of two-man teams, four hours on and four hours off. Michael explained the matrix he worked out: By alphabetical order, Bruce would team with Dave and Michael would team with Moose. In three days, we’d switch. Bruce would move to the back, and Dave would be in front. Moose would now team with Bruce, and Michael would team with Dave, but Bruce would lose two hours and have to hold a six-hour shift, while Moose would gain two hours.

Got it? Or was it the other way around?

Michael assured us it would all even up in the end. With confused looks, we asked him to draw the matrix on paper to show us its simplicity. By the time the diagrams for two weeks were complete, they looked suspiciously like a flea-flicker play for the last seconds of a high-school football game. Our laughter bounced across the waters as Hope skipped east along the 1,800-mile great circle route tracked by Loki, the nickname for the B&G Zeus chart plotter. Loki, I was told, is the mythical Norse character known for being a trickster. I was assured that by the end of the trip, I’d be witness to Loki’s mischief.

The departure forecast had come with favorable news. The weather would be fair for a good portion of the following week, with moderate winds on the beam or farther aft. It also came with a strange addendum: an ice report in the form of a grid dividing the waters we’d sail through, indicating the number of icebergs in each block of the grid. We’d have to keep a keen eye out until clearing the ice zone at 46 degrees west longitude. I had experience with ice reports and explained my limited knowledge of the characteristics of ice in the event we encountered bergs. Most important, sail to the windward side. Keeping a vigilant watch, we excitedly anticipated a sighting, but unfortunately, there would be no icebergs on this trip across the Atlantic.

In the stable conditions, Thor, our Hydrovane wind steering system, handled the helm while Watson, our Watt & Sea hydrogenerator, provided power, augmented by the solar panel. By sidelining Olaf, our electronic autopilot, we limited our electrical usage and allowed our alternative power generation to keep pace. In livelier conditions, we’d employ Olaf and generate additional power from the diesel engine as needed. When making speeds of 7 and 8 knots, there was enough power to run the systems, especially when taking turns at the helm to avert boredom.

The long passage morphed into indistinguishable days as the small cursor on Loki progressed across the chart. Each click of 100 nautical miles generated a celebration. The celebrations added up, along with the sightings of whales, dolphins and the endless community of seabirds following our wake. The long miles gave us plenty of opportunity for calculating time and distance equations, and no passage is complete without a pooled bet on arrival time. In our case, the pool consisted of $10 per crew, with the winner obligated to buy drinks in Dingle. At the halfway mark, we allowed a change of prediction if accompanied by an additional $20 fee. By the time we reached Dingle, we were determined to impact the local economy.

With 700 miles remaining, our weather update forecast a frontal passage the following day that would continue to carry us east quickly. A more significant frontal passage was developing for the last few hundred miles into Dingle. Commanders’ Weather predicted 40-knot winds from the south-southeast ahead of the significant front, with the winds backing to the southwest at 25 to 30 knots afterward. Our last few days into Dingle aboard the compact 32-foot Najad would be sporty, to say the least.

As we laid out the timeline of the frontal crossing, we prepared Hope for the heavy weather by securing everything in place and setting up storm sails. Freeze-dried or hand food would replace the magical concoctions from Michael’s galley. We changed the watch system to two-hour shifts so the watch crew could rotate through 30-minute turns on the helm if necessary. As the weather approached, the winds built to 25 then to 35 knots with a gust to 38 forward of the beam. Olaf handled the steering well under the reduced sail plan and an adjusted course that took us north of the rhumb line.

With each watch change, we noted the storm’s progress and aligned our expectations for the next several hours. At midnight, Michael and I took our watch, anticipating the front crossing and the inevitable wind shift to the southwest. Like clockwork, over our two-hour watch, the winds backed to the southwest and decreased to 25 knots. With the ease and change in direction, we slowly adjusted Hope back onto course. The winds remained at 20 to 25 knots for the following two days, giving us a beautiful ride among giant swells of crystalline blue. Sighting the ghostly shapes of the islands off the Dingle peninsula built an air of excitement to the completion of the crossing, a first for Bruce, Moose and Michael. Blasting up Dingle Bay through the afternoon, we arrived in harbor to a soft, gentle rain we’d come to know as “Irish sunshine.” After 13 days at sea, Dingle provided a warm welcome and a comfortable rest.

After ample celebration in Dingle, Hope sailed on to the famed ports of Kinsale and Cork before arriving in Howth outside of Dublin. The friendly Howth sailors filled us with local knowledge of the routes and passages we’d encounter on our trip to Fort William: snug harbors, swirling whirlpools and tidal rips — those passable and those to avoid. With great reluctance, after a wonderful few days in Howth, we released our dock lines and headed for Port Ellen on the island of Islay. The unfavorable weather provided little wind for sailing, but we were assured, if we took too long, we’d have all the wind we wanted on the nose. We opted to motorsail along the beautiful coast until morning, when the breeze freshened, allowing us to make the harbor at Port Ellen before the heavier winds arrived.

After a long walk to the petrol station for fuel and a trip to the local distillery for scotch, we relaxed in the hotel bar for an evening meal and local entertainment. Providing some entertainment of our own, we tested the local fare of haggis and Scotch whisky. Two out of the three of us found the haggis edible. I was the exclusion, unable to even try it.

As forecast, the weather turned against us, forcing us to stay through the following day and set a departure for 0300. In the early dark, with driving wind and rain, we untied our dock lines and headed out, hopeful the forecast would prove accurate and the wind would turn favorable as we approached the narrow passage between the islands of Islay and Jura.

We planned our departure around the tidal rapids, both the ones with us and the ones we wanted to fight. We chose to have the tide at the top of the bay near Fort William with us, which required us to take the full brunt of the tide in the narrow passage. Making just 3 to 4 knots over the ground under full main and 25 knots of wind, this may have been the only time in my life I proclaimed, “Thank God it’s blowing 25!”

After two hours of battling tide and conflicting emotions — anxiety over the danger and elation over the beauty — we exited the narrow passage heading northeast up the long finger of Loch Linnhe. Beautiful vistas opened and closed with the foggy rain surrounding us. By late afternoon, we sailed through the last of the tidal rapids with the current helping us rip through the eddies and swirls. A large sailboat at the mouth of the Caledonian Canal at Fort William became our raft and neighbor. Together, with a friendly young couple heading south, we walked along the canal to share our stories over dinner and a pint at a local pub.

The next morning started with coffee as the loch tender opened the sea lock for us. Soon, a steady rain had begun as we locked up the seven steps of Neptune. At the top of the steps, drenched and cold, we walked along a path to a small coffee shop we passed to take a break. The canal and its 27 locks would take three days to traverse, allowing for the exchange of stories with the many sailors and tourists watching our flotilla pass.

Our most anticipated portion of the canal was sailing Loch Ness. Leaving our pontoon early, we entered the loch and immediately set our big green chute. With a light wind blowing the length of the loch, we ghosted along, imagining the monster below us and what life would be like in one of the remote dwellings along the coast. All to no avail: Nessie stayed hidden, frightened by the jolly green giant spinnaker.

Exiting the canal at Inverness, we began the last and most anticipated passage of the trip: crossing the North Sea to Norway. Pondering the weather options for late September on the North Sea, we had only a narrow window that would allow us good sailing with 20 to 25 knots and the ability to cross in two days. Setting up for this window required sailing the length of the bay to position ourselves at Whitehills before departing the following day for the open North Sea.

We carried the fresh wind across the North Sea, sailing between giant oil rigs speckling the horizon. Like small cities, they provided navigational stepping stones. With the wind holding at 20-plus knots, we approached Norway in a heavy following sea. In 5- to 6-meter seas, we picked our way into the craggy coast, closely monitoring the GPS position as spatial perception frazzled our nerves. Waves crashing on the rocks and islands seemed way too close for comfort after sailing the open expanse of the North Sea.

Approaching the coast, I found Michael helming in a teary, joyful, emotional moment with a rainbow behind him and the reflection of the Norwegian headlands in his glasses. He was living the dream he began 40 years ago after taking the helm of a sailing boat in college. In that first sailing moment, he knew one day he’d sail his own boat across the Atlantic to visit his homeland. As each mile drew us closer, I could sense his peace from the spiritual and emotional happiness he was living. With a final turn behind the lee of an island, we settled into the beautiful harbor of Mandal.

Secure in Mandal, we waited out the increased adverse winds before finding a gentle weather window to carry on to Sweden. The final leg of this long journey was calm and serene. While it was necessary to motor much of the way, the clear skies, warm sun and stunning nights — complete with drifts of northern lights — made the perfect time for reflection on this great adventure.

In the morning rain, Hope was secured to a pontoon at her home docks in Orust, where she had come to life just steps away, in the building sheds. As we absorbed the end of our journey, I could sense Hope‘s relief and pride, having seen much of the world her neighborly sisters hadn’t. She floated proudly at the Orust Yacht Services marina as we contemplated the return trip next summer over celebratory pints. Hope‘s trip home will take her along the westward Viking route via Norway, the Shetlands, Iceland, Greenland and the Canadian Maritime provinces. If it’s anything like our crossing, it should be one sweet ride.

Dave Rearick is a lifelong sailor who hails from the southern shores of Lake Michigan. His passion for singlehanded sailing earned him the prestigious Mike Silverthorne award from the Great Lakes Sailing Society. After campaigning his Farr 40, Bodacious Dream, in races in North America and Europe, he set forth on and completed a solo circumnavigation. Dave’s much-anticipated book on the trip, Spirit of a Dream, is scheduled for release this summer.